Back to this wilderness.

It occurred to me one day on my porch while staring at the surrounding woods, that at some point less than one hundred years ago none of those trees were there. The land has beautiful eighty foot oaks, some maples, tall thin pines and various other hardwoods including black walnut trees, which I am told can provide the ingredient necessary in the liqueur, Wild Spiced Nocino.

The branches protect birds as diverse as red-tailed hawks, downy woodpeckers, and countless chickadees, and they are habitat to other wildlife including one flying squirrel we spotted a few years ago when his tree fell. The squirrel was fine and found a new home in a white oak. And of course the fox which frequents the lawn.

But a hundred years ago this was just land, sandy land, edged by the running Rappahannock River and backed by equally treeless farmland. A century before that these nearby plantations provided food for the region at the expense of slavery, and some slave descendants remain, selling vegetables at food carts out on the main road, or working the bay as watermen, telling stories about how the Chesapeake is just about farmed clean every season by crabbers at the mouth or the headwaters leaving nothing left for those working the midland shoals.

This area hasn’t changed much in one hundred years.

It is like this everywhere, the coming and going of things. In Manhattan a few hundred years before the wild construction on bedrock, coyote and deer were common. It was hilly (Manhattan means land of hills), and where the United Nations stands once stood grand oaks. The Lower West side was a sandy beach, and ecologists say if left to do what it wanted, most of the upper west side would be covered in trees and vines, shrubbery and wildflowers inside twenty years. I can’t imagine what my house would look like if left untouched. When I don’t mow the lawn for a few weeks it looks like a refuge for timber wolves.

But these trees weren’t here a century ago and I sat on my porch and wondered if there had been other trees or if this land was barren, or was it used by the Powhatans, or was it home to some former slave family, or just a dumping ground. Evidence is scarce, buried beneath the roots of this small forest. One guide at the Mattaponi center not far away told me this had always been hunting ground for the Powhatan. I’m glad it wasn’t a burial ground. I’ve seen Poltergeist.

This happens to me everywhere I lived; I like to imagine what was on that spot one hundred, two hundred, a millennium earlier. The house I rented in Pennsylvania was used as a hospital during the civil war. Before that it was a farm. Now it is a Real Estate office. The maples which lined the road and shaded the living room are gone. Someone planted new ones but it will be decades before they mature. My house in Massachusetts was a fish market a century before I sat at the kitchen table looking out at the Wachusett Reservoir and wrote a book about Vincent van Gogh.

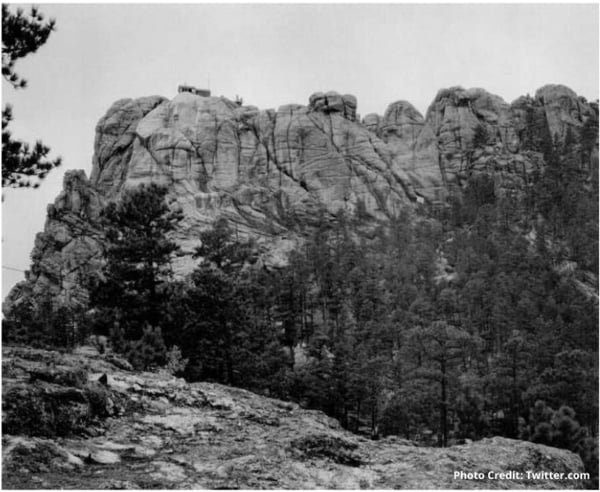

Purpose moves on with time. Maybe that’s why I’m so mesmerized by the Prague hotel I always stay at. It was the same building seven hundred years ago that it is now, only then it was used by servants for the castle. In Russia most of the lands upon which St. Petersburg is built were not lands at all, but marsh, and Peter the Great filled it with stones to create his “Venice of the North.” And a Lakota medicine man, Nicholas Black Elk of what is now South Dakota had a dream in which he saw “Six Grandfathers,” for the directions–North, South, East, West, Up, and Down– and his dream was the vision of a mountain that was to be left alone to symbolize kindness and love and wisdom, as present in human grandfathers, and it was to be carved only by wind and rain, and so it was. Until 1927 when Gutzon Borglum “began his assault” on what became Mt. Rushmore.

I like knowing but I like not knowing too, like accepting truth, like unearthing reality, like facing our fears. What was on the land where you are now? What will be? What traces of us will linger, offering a hint of now to some other now?

This house is the only house which ever stood on this former hunting ground, and is the only place I have lived for this long–twenty-six years. The house is made from western pine forested on land which I assume is either now empty of trees or filled with young pines waiting to become log homes. What will be left a hundred years from now? Will someone sit on this same porch and look right out toward the bay once these oaks have long fallen? I know this house, this land, is a “hotel at best” as Jackson Browne despondently points out. “We’re here as a guest.”

I know nothing is as permanent as nature, despite the constant changes. It simply isn’t going anywhere. We are. So I like to remember that a century ago farmers sat not far from here and talked about the bounty in the soil, or talked to 19th century watermen about the changing tides. And I like to realize that a hundred years before that the nearby swampland, now home to so many osprey and egrets, was a major route for runaway slaves. They’d have been safe in these woods, if there were woods then.

I like to do that because it reminds me a hundred years from now perhaps I will have left some sort of evidence of my passing through; even if just in the cultivation of language, the farming of words.

So I sit on the porch and listen to the wind through the leaves. It is now; it is right here, now. Sometimes at night we stand in the driveway with the telescope and study Saturn, or contemplate the craters on the moon—both here long before us and in some comforting way, long after we’re gone–all of humanity.

In spring and fall the bay breezes bring music even Vivaldi would envy, and I’ll listen to his Four Seasons, written nearly four hundred years ago, and listen to the wind through the leaves of these majestic, young trees reaching eighty feet high, and be completely, perfectly in the moment.

Despite the warming trends, the extreme tendencies of weather, the fragile ecosystem which sustains life, nature is still the only place I have found that really doesn’t change. It never has. Ice ages and dust bowls will alter it to be certain, but she has mastered the art of adaptation, and eventually some seed will take root.

I live surrounded by farmland. It was once forest. Indiana was a territory.

The farmer north of my property has sold his parcel for a solar farm. I’ll miss the corn and soybeans.

Nothing stays the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose this is better than a bunch of houses or apartment complexes.

LikeLike