I started to read five books but simply could not get through them, so they sit on my shelf just daring me to take another shot. Understand, I did not major in English until I received an MFA at Old Dominion University in 2004, and that was strictly creative writing, non-fiction. At Penn State, my Masters’ were in art and humanities, and, sure, that included lit courses since the “humanities” part seems to think it relevant, but my undergraduate degree in mass communications, specifically journalism, didn’t call for it either.

Call me lucky.

As a writer I have read tons of books in my life just out of curiosity or research, and my shelves are filled with non-fiction works. Along the way I picked up books because of the cultural relevance when traveling. I have shelves of works I’ve read from Russia, the Czech Republic, Spain, and various locales in Africa, and good ‘ol American letters as well, including most of this country’s classics like Twain, Steinbeck, and Walker.

But still it has always been a struggle for me to sit and read at length, which my father was always able to do, and through him I read many volumes of Michener, Grisham, and historical works, as well as the great sports writing of Roger Kahn. My son, too, is a prolific reader and every once in a while will give me a book knowing I will like it, and I always do. When he was small I read to him tirelessly, and to this day I can recall just about every story of Pooh, Curious George, Richard Scary, and various zoo books. But that was fatherhood, not reading. Now, I simply don’t turn to literature out of habit. Some of it is my career for three decades demanded I read endless stacks of papers, and also stories and books in preparation for a course. Part of it is when I’m writing something, I avoid reading material not relevant to what I’m working on. And part of it is I simply prefer music, walking, talking at a pub with friends, to reading.

Still, as a humanities professor and a human being who knows books exist, there are a few works I simply know I should finish, but as of yet have not.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh. This earliest surviving literature in the world, and the second oldest “religious” text, was written more than three thousand years ago. It’s an epic poem about, well, Gilgamesh. I’ll get there. I do like epic poems—Canterbury Tales, Sir Gwain and the Green Knight, for instance. But the Gil never worked for me.

- Beowolf. Okay, to be fair, I have read this one, but that was so long ago and I think I skimmed it because it was, well, boring as hell. So now that I’m some months older I need to give it another shot, particularly since my son has a translation by Seamus Heaney, whom I deeply respect as a poet and writer. It is sitting there, daring me to pick it up. But it is so close to The Far Side Complete Collection, I’m afraid the competition is simply too strong.

- Infinite Jest. You’ve got to be kidding. 😊 The reviews as well as my peers in the writing world told me I must read this, and my more astute students said it really captured their generation, which encouraged me to read Wallace’s book, and I tried, I swear, I tried. Once I even made it to page 125. My goal was to get half-way through the thousand or so pages, but no. I put it down and thought, Surely, you…

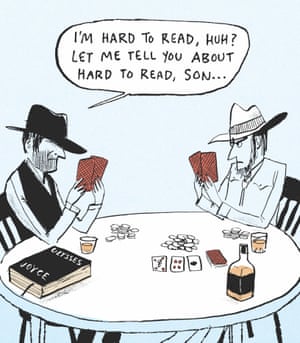

- Ulysses (the book by Joyce, not Tennyson’s poem which I do love). To my credit, I know a Joyce scholar who said he couldn’t get past page twenty-seven the first dozen times he tried. But still, I loved Joyce’s other works, admire Wolfe and Hemingway who deeply admired Joyce, and, well, I’m forty-two percent Irish, so. I’m not sure what my problem is but I do feel better knowing just about everyone I know who has tried to read the damn thing apparently had the same problem. First of all, I’m not nearly as smart as I should be for the life I have read or the career I have had, so there’s that. But more, I speak English and Spanish with relative ease, dabble in traveler’s Russian, but have never been able to absorb Joycean. Maybe if he drew me a Portrait I’d find a way in.

- Middlemarch. A writer friend of mine once said to me about this book, “If you’re going to spend that much time describing a woman’s blouse, that blouse better kill someone before the book is over.” I actually have this on the list as an example of the primary reason so many of us don’t read works we think we should—we find them boring. I know I can read the thing, and I know I’d understand it; George Elliot isn’t that complicated, and she didn’t exactly make it difficult to read. It simply bored the crap out of me, all the seemingly useless details, endless descriptions. I don’t need constant conflict, but I want something a bit more than a fashion lecture. I know that’s not the point, I do. But I also know I’m a modernist, a minimalist with a degree in journalism whose primary influences were of that profession, who learned to get to the point and leave off the fat unless it is absolutely necessary, and I still have difficulty finding so much of Middlemarch necessary.

The truth is, these books aren’t in my comfort zone, and that’s why I keep them near. Hardly ever does one not gain something by stepping out of the comfort zone and challenging the norms of life. In fact many of my daily activities were, at one time, outside that comfort zone. My routine was at one time not my routine.

It happens.

Adding a book to my list of things to do instead of watching another repeat of a favorite show I’ve seen, and I watch again because it is familiar and predictable and safe; and so I know how my night will go, when I will laugh. But a new book challenges that, like anything new to our routine challenges us to grow a bit more.

Slowing down enough to actually read words on a page is not on most people’s minds, schedules, or even anywhere in their peripheral view of life. It is not “productive” in the contemporary take of that idea, it is not “on the way home,” or “part of my routine.” But step to one side for a second, let the traffic go by, go for a walk instead of, say, not going for a walk. Learn the name of a new bird—just one—each week. Then see if you can spot it. Honestly, how much time does that take? Routine follows the new, it never precedes it. Then it becomes expected. Then it becomes habit. Then not doing it seems wrong. And as for boring—well, the truth is, most of us get bored because we believe we should be doing something else, or we think that whatever it is that bores us isn’t worth our time, despite the obvious reality that we simply didn’t give it a chance, slow down, take a breath, and let it have its way for a while.

I am reading, however. I just finished Ice Walker by James Raffan. Incredible journey with a polar bear family. Escape Envy, poems by Ace Boggess, who has one of the finest voices I’ve read in the genre. The Total Skywatchers Manual, which my son gave me for Christmas, and I try and learn a little something each week about the stars. Some of it takes, most not, but at this point I’ll take what I can.

I don’t know how long I’ll remember how much I enjoyed a book, will be able to recall the plot. Some books, already, I see on a shelf and know I enjoyed them immensely, but please don’t ask me what happened. I do know that right now, for a little while anyway, I can feel the arctic cold, get tense by the melting ice, as Raffan beautifully and tragically describes the protagonist bears’ trek. Later, I will know a few stars tonight, drink some Blue Lotus Flower Tea and enjoy the peace of stepping outside of myself for as long as I can, understanding fully that in my six decades so far, it has been when I push myself out of routine, challenge myself to understand what I thought I could never understand, and find the beauty in what I foolishly perceived as boring, that I have been truly and fully alive.

“It is a narrow mind which cannot look at a subject from various points of view.”

― George Eliot, Middlemarch

Gilgamesh, huh? Let’s see…hero is a jerk, hero makes friend, they go kill stuff, they piss off a goddess, friend dies, hero seeks immortality, hero fails test, hero goes home, hero becomes better king. Come to think of it, that covers much of Beowulf as well, plus a dragon. There ya go.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool. Four left

LikeLike

I believe any of these 5 are more interesting than Ulysses or Middlemarch, which I was forced to read long ago. I am pretty sure I will not read them again. Interesting is good enough for me.

Growth of the Soil by Knut Hamsun. My favorite writer. His descriptions of nature verge on the mystical. Usually, I don’t tolerate racists but I have forgiven him for his intolerant views, blaming those perspectives on madness and trauma in youth. He also had 2 brain hemorrhages. Recovering from one is difficult, recovering from two is punishing, returning to normalcy with the medical care of 70 years ago would be nearly impossible.

Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol. No one can mock rich, pompous aristocrats better than Gogol. I was enthralled at the detail with which he describes rural Russia.

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. Possibly the first novel. Everyone knows what a quixotic quest is simply because it seems to happen in almost everyones life. Yet, fewer have read the 1000 pages of Don Quixote despite the seismic shift it caused in literature. I am guessing that the fact it is not in the 5 on your shelf is because your have already read it.

Post Office by Charles Bukowski. He wrote about the poor and their ordinary lives. Bukowski, like Hamsun, is not someone you would want as your next door neighbor as they both had abhorrent views. The succinct, spare character descriptions can be hard to read but he describes a world few have ever seen. Bukowski offers no wilderness descriptions but rather a wild inner city.

Any collection of short stories by Anton Chekov. His descriptions of the Russian steppe has made me feel like I have been there.

In another lifetime I wrote compilers. A compiler translates one computer language to another. So it was an honor to have met Boris Babayan, a compiler writer and hardware designer who was the father of Russian computing. In order to launch space rockets it is necessary to have powerful computers for the calculations of trajectories and Babayan helped developed them in Russia. He brought his group to work with us in the 80’s. The group had a delightful Russian woman whose name I cannot remember now. I assumed that in Russia, science education was similar to in the states, where engineers do not normally read widely in the humanities or literature. So in trying to make conversation, which can be hard for nerd engineers like me, I asked her if they taught Chekhov in the schools. She said that yes, they did. She said in fact that Chekhov was considered to be similar to the American writer O’Henry. I thought this was an especially insightful answer because it spanned both our cultures. It was something I had never considered, even though Chekhov is my favorite short story writer and I had read a great deal of O’Henry growing up. You may recall that O’Henrys stories had plot twists in his short stories with surprise endings. And this is indeed the way Chekhov also wrote his short stories.

LikeLike