I have a lot of shit.

Books I’ll never read again, clothes I don’t wear, boxes of frames and a stack of artwork I’ll never hang leaning against the wall next to the bureau. I have enough pottery to supply a small restaurant, enough reusable grocery bags in my house and in the trunk of my car to carry away the frozen food isle of Kroger, and a shed full of tools I didn’t use when both me and them were newer.

I have scribbles of notes for articles and essays, folders of rough drafts for books and short non-fiction I never read or even attempted to get published, sixteen previous versions of a book which comes out in a year that doesn’t resemble any of the first fifteen variations.

Even when I get away from it and go for a walk down the hill to the river, I have too much stuff. I have obligations both financial and professional that weigh heavily, an overwhelming desire to call Letty or Dave or Dan and just talk like I did every few days for three, four, almost five decades, and sometimes a powerful flash of memory of my father so real I can hear his voice next to me. Those moments can be debilitating, and I just want to swim away. When that happens, I carry it all home and sometimes write about it, sometimes lay down and try and sleep. I lay down and not sleep at all a lot.

A few days ago my son and I took the ferry to Tangier Island, eighteen miles into the Chesapeake, and we walked the historic, tiny slab of sinking land. It was good to slap the world’s largest estuary between me and my stuff, walking around, talking, noticing the birds, the friendly residents, and watching the watermen do their thing the way their ancestors did since Cornish settlers arrived in the 1680’s, more than fifty years after John Smith rowed by and took note. A lady in a golf cart next to Lorraine’s restaurant where we had fresh soft shell crab sandwiches spoke to a friend of hers in a Cornish accent the islanders are famous for.

And we had ice cream.

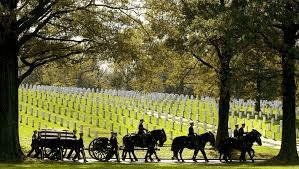

But all of that was all I needed to clear my head and not carry around the volumes of concerns back on the mainland. I was in the moment, which is quite a rare thing for anyone these days. I have noticed that when I travel—Prague, Ireland, Spain, especially all those trips to Russia, even the pond of lily pads across the river where my son and I often stop to listen—I am completely present, uber aware of my surroundings, the people, and my memory sharpens so that I can write about it sometimes years later and still smell that moment, still hear a veteran’s voice telling me about “the time that…” Absolutely present.

And I come home after those moments and look around at the stacks of magazines I won’t read again if I ever did, the boxes of ornaments too many to hang them all, grade books from my early teaching years, relics of a time I wish hadn’t happened to begin with never mind reliving it, and I wonder why I still have it all.

When we walked the Camino de Santiago, it took about a week to shed the sense I was forgetting something, to ease up on the worry that something needed to be done. It took only a few more days to remind myself that at all times I am indeed here, breathing in and out, moving along, celebrating the passing of time, and everything else is needless no matter how sentimental we are about stuff. We rarely stop and appreciate the fact we are actually alive to begin with, standing here, able to negotiate the next moment however we desire. I forget this most of the time, and I wish I didn’t.

Many, many years ago I went to a wedding reception on the shore of Lake Erie in the small village of Angola on the Lake. I stood looking out across the water not unlike I do almost every morning when I head to the bay at Stingray Point and stare east, and Fr Dan, who had celebrated their marriage, walked to me and we talked. I remember he said I seemed quiet. I told him I wasn’t sure what to do with my life. He told me the normal Fr Dan stuff like God will show me the way, and I’m young and have so many options, and more of what I’ve heard him repeat to me and others in the nearly forty years since then, but I knew all that. So I said something to the effect of, “I suppose just knowing no matter what else all I need is ‘me,’ alive and functioning, to start over if things don’t work out in whatever direction I choose and to truly enjoy the ‘passing of time.’” He laughed and put his hand around my shoulder and said how right that is.

But we don’t really mean that. We work hard, we gather memories and even though we stack them next to the bureau or on closet shelves, we need them there to glance at once in a while to know there was some reason and rhyme to our pilgrimage until now. Of course I can land on my feet and start in a new direction at any time, knowing that in about a week that routine will realign my anxieties and I’ll be fine, and all I’ll need to carry with me are memories of those I have loved. Yes, that is all true.

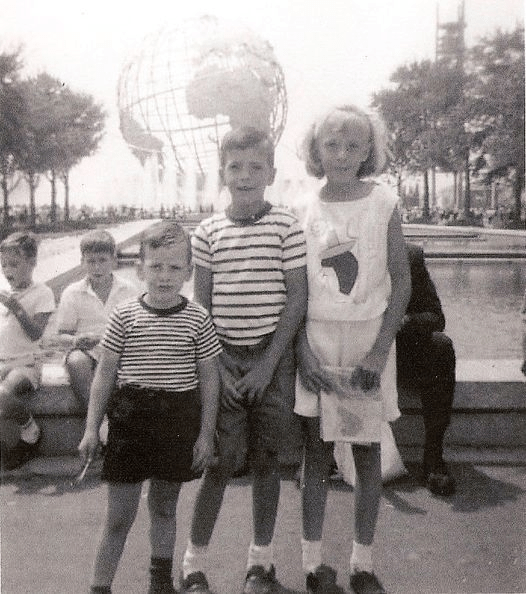

But I like my shit. The funky photos Valentine took in Russia, and the photo Letty had framed for me of four ladies on a bench; the stacks of brochures and pamphlets from state parks and museums my son and I have hiked and visited for nearly thirty years, the signed books from authors I have had the pleasure to talk to and read with, the tins of pins from Soviet shops and Czech artists’ studios. The sloth birthday balloon and a crazy little light-generated cat from someone who can finish my sentences for me, the folders of drawings from my son’s youth, the small bottle of absinth I never opened.

The miter box my brother bought me and the rug of seascape my sister made when I was in college. My mom’s large Dopey Doll. Shells from a walk with a friend on the Gulf of Mexico and a nutcracker my son painted when he was young.

I have so much stuff, but it all reminds me of what an amazing pilgrimage it has been.

In two years I’m going back to St. Jean Pied de Port, France, to start walking again, south to Pamplona then west to Santiago. I’ll carry a pack with just enough to know I’ll be fine. And if I should stumble upon mementos to carry home, I am sure I can find someplace to put them.