This one’s for me.

When I was out west we hiked uphill (because the West is uphill) to a waterfall. I’m not sure of the elevation but it really doesn’t matter since I live at sea level and the waterfall is not. My home is about 80 feet above sea level and a short stroll down the hill is zero.

A few days before the waterfalls we were at just above eleven thousand feet; June, and still there was snowpack on some of the trails. At night we had a fire going, of course to toast peeps but also to keep us warm. In the cabin we kept the wood burning stove going all night. Back home the ac was running strong. Back at zero elevation. that is.

On the way to the waterfall–it was hot that day–I had to stop more than a few times due to my unconditioned lungs. I had no issue with my heart or legs; no, I felt pretty strong actually. It was just the lungs which in my mind looked like the deflated oxygen masks in planes. I wanted to quit; it was clear I wanted to quit, but it was also clear I just needed to catch my breath and push on. “It’s just a little further” translated to me to those days driving my son long distances and from the back seat I’d hear an impatient, “How much longer, Daddy?” “Not far,” I’d say, as if a two year old could translate “not far” into some sort of calculable distance. Yeah, that was me on the mountain as kids–I’m not kidding, kids!–ran past. I reminded myself they’re closer to the ground and need less air, and “it’s just a little further” to me translated to “move your ass for Buddha’s sake, or we’re going to have to make camp soon.”

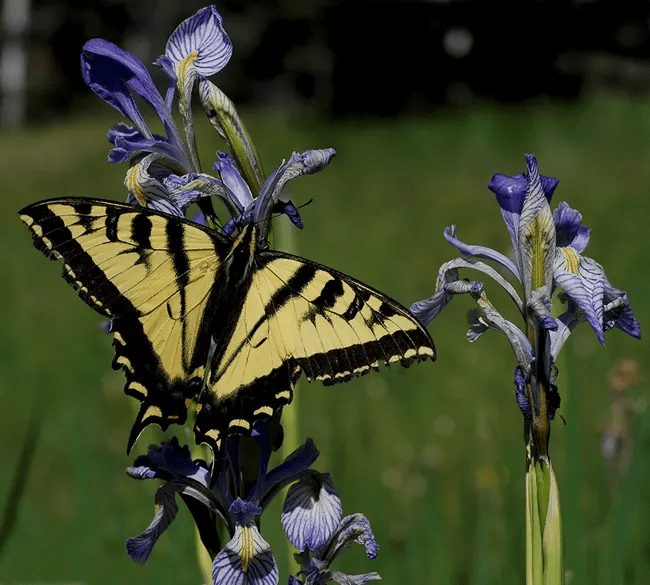

I made it. I sat on some rocks and watched the majestic water fall from other rocks, down to a pool, off into a creek, down the mountain past the path we just hiked. I quickly gained my energy back as the issue was my lungs inability to climb at that altitude, not “be” at that altitude. A few days earlier we were at eleven thousand feet and I was fine because there was little steepness about us; it was a casual altitude gain. Plus it was colder. But there I sat outside Ogden, Utah, having climbed what I swear was the Matterhorn and I watched the sky grow bluer, watched the water mist up into the trees, and watched the world below try and make excuses for itself. I can’t recall ever feeling so at peace.

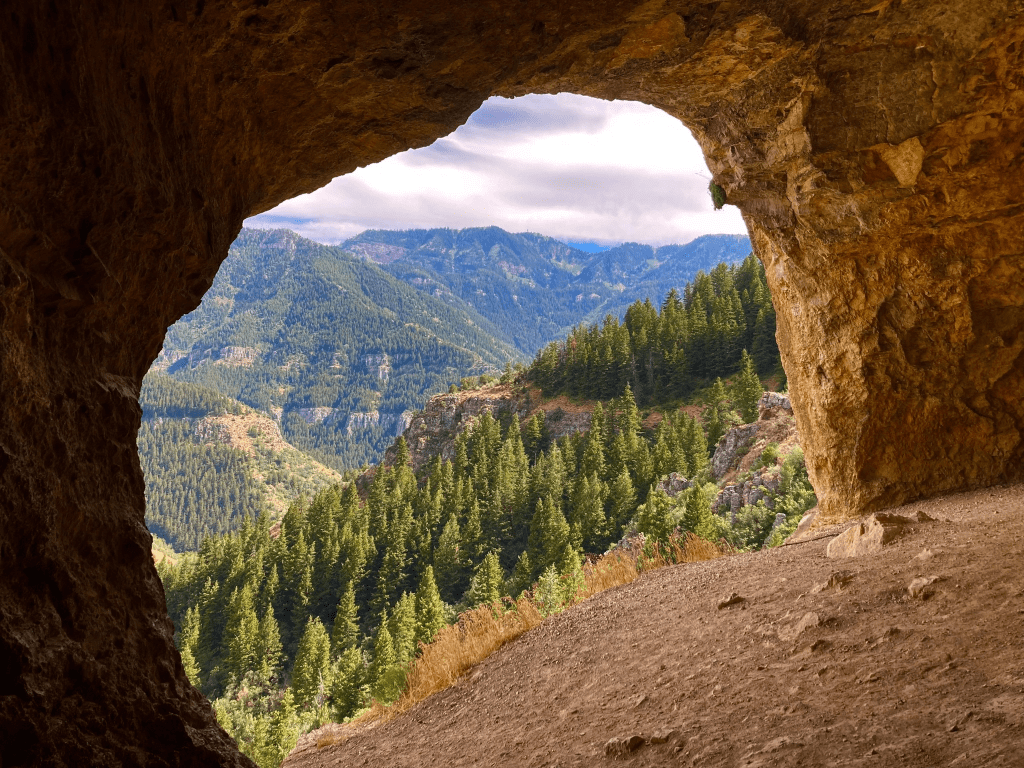

A few years ago we did the same thing not far from there to a place called “Wind Cave” and that was more than just a steep climb, for a flat-earther like myself it was like scaling The Freedom Tower, but we climbed and a few times I wanted to quit–apparently I’m not adept at steepness yet–but I didn’t, and when we came around the top slope and walked back down to the opening of the wind cave, there was nowhere on earth I would have rather been. And so again in the mountains, and then again at the waterfalls.

Fast forward, for that is the theme here: Today I wondered about two distinct things: Why is it so hard for me to do these things when I used to have no issue with them when I was younger? and why did I push myself to finish when I could have so easily stopped without objection?

Let’s get the age bullshit out of the way first. Yes, there are conditions which can slow a person down as we age, and it makes it harder to do what we could do with ease decades earlier, but all things being equal, one can battle a decreased metabolism by eating right and working harder. The list of reasons those antiquated excuses are irrelevant aside, internal motivation has more to do with accomplishment than external excuses. I have some experience in fitness and working with people whose challenges could not be calculated, but who, with the right motivation and persistence, reached their goals. So why is it so hard for us other than absolute and flat out indifference as our minds are occupied by other issues? And two, what changed? Why did I push on despite my better judgement only to find out I was capable of more than I thought? The company? Partly. The kids running past? No. The beauty at the end of the hike? I promise that wasn’t on my mind while dry-heaving into the creek.

No, something different took over.

I wanted to do it for myself.

***

I went to the Y today, again. I’ve been going on and off for some years now, though I took a break during Covid and another break not during Covid. I get bored, or I find something else to do, or…or…or…I lose some weight and I get in shape then I tumble back. This is normal. While my old boss at the fitness club could take an eighty year old and make them feel young and able to accomplish anything–and they often did–it was more normal for a healthy, capable young-something to cave at the first sight of a donut. Enter me.

But I have gained less time, and that is something they and most of the members I trained when I was there did not have at that age back then. It takes a while to understand that all we gain as we age is less time.

Tick tock tick tock tick tock people; times ticking away.

When I did the math this past weekend as the calendar turned on me again, I realized the list of things I plan to do is longer than the remaining time allotted, and that’s if I’m generous with myself. So I went to the Y today just like any other day, but this time I wondered if I could push it a bit, so I increased the incline on the treadmill and turned up the mphs. And again, until my heartrate was safely beyond what I normally do, until I was sweating, which I rarely do, and until I was at the point I never have been to before at the Y–the point where I wanted to quit for a reason other than boredom, so I pushed the dial up a bit more and for ninety minutes I climbed to the wind caves and to the waterfalls, I climbed Mt Wachusett in Massachusetts and to the upper falls of Sabino Canyon near Tucson. It brought me back to those days, first, when I taught classes at the club and I had to push myself because the class wanted to be pushed, and then earlier when playing tennis, and I wasn’t done until I dropped on the court, spent.

Why? Because I want to ride my bike to Coos Bay, Oregon, and I want to go to Seattle and hike Mt. Rainer with my cousin, and I want to make the climb to the waterfall a stroll, a meander. Because I saw the clock. I didn’t want to look; I really didn’t, but I did and I saw it as the large digital numbers clicked over, and I did the math because I’m pretty good at math and the distance from here to 80 is barely enough time to love anymore, barely enough time to dream anymore.

Something was different today. Something clicked. It’s that there are going to be a plethora of things out of my control as I move forward, so I’m going to take control over those aspects of my life I do have some say about. Of course I’m not going to get back to my club weight again, which is fine since I forgot to eat from 1983 to about 1988, but I am going to get to the point I believe I can if I decide to. And that might be all I need during this last push to the summit.

And by the way, we do these things at this point in life for ourselves, no one else, and that’s different too.

This time it’s for me.