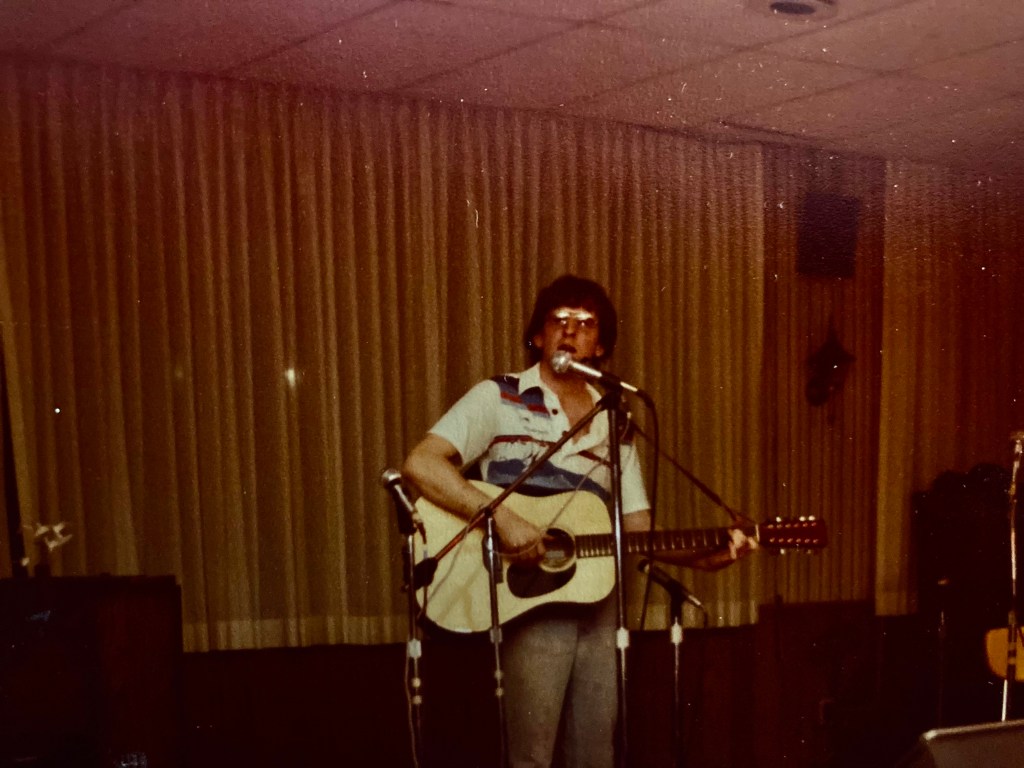

On June 22, 2002, my sister sat at our parents’ kitchen table and recorded an audio interview she did with them about their lives, about life during the depression and World War 2. She asked other questions, and just like Terri Gross on Fresh Air, did a great job of bouncing off of their responses. She sent copies to my brother and me about five years ago, and when I sat to listen to them, a few things struck me. One, my father was precise in his responses, and my mother was hysterical in hers. He was 77 at the time, and Mom was 69. But what hit me hardest was hearing our father’s voice for the first time in half a decade. I can hear his voice in my mind, of course, but to actually hear his voice like he was sitting there made him young again. The last few years of his life I was around him all the time and his dementia grew worse and worse. So when I played the cd, I heard not just my father, but my father younger, still alert to everything. It was nice to push past the sound of his weak and confused voice that had filled the corners of my mind and hear him as he had been. Ironically, at the same time it makes it hard to listen.

About two years ago while out to lunch I randomly recorded a video of my mother talking about something. I don’t remember what and the video is gone, but the idea took hold, and for the last two years every couple of weeks when we were at lunch or getting coffee, I’d ask her a specific question, or I’d encourage her to remember a particular time in her life. Note that she is one of the funniest and smartest people I’ve ever known, and understand too that she has had quite the life from the streets of Bushwick, Brooklyn, to Long Island, to Virginia Beach, and now in Williamsburg, Va. There are fifty plus videos here, but I recorded more than a hundred and deleted many. Some were redundant, and some in the past year or so I got rid of when Mom would struggle with a memory, or lose track of what she was talking about.

Still, this is decidedly not about Joan Catherine.

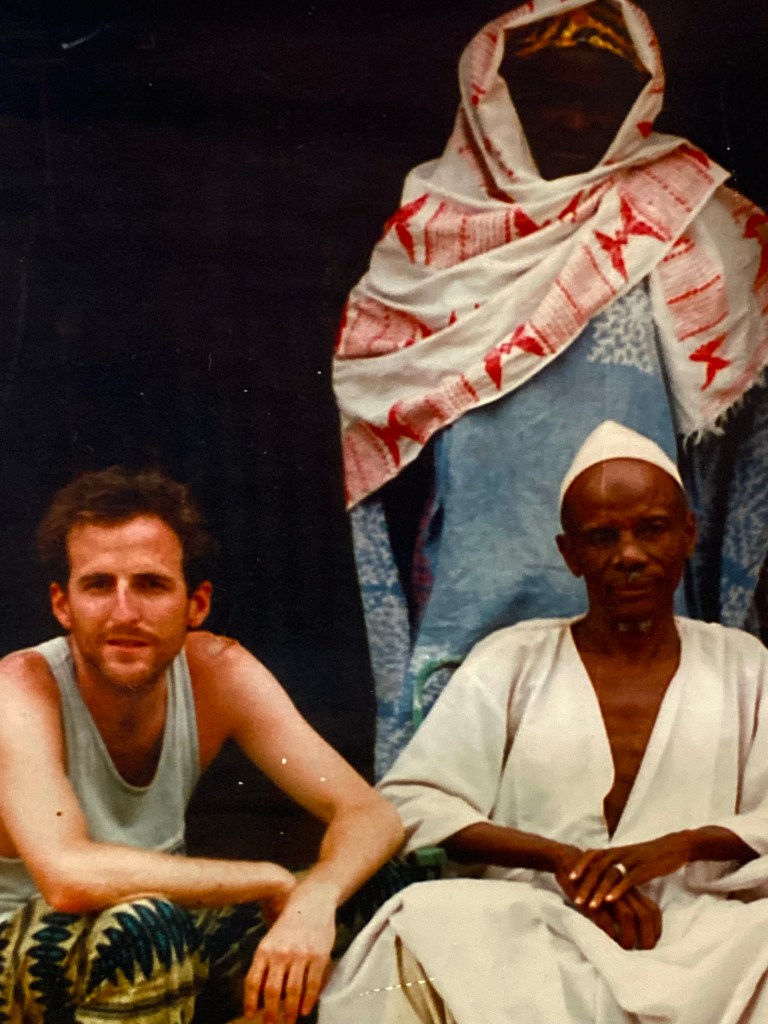

It is about time. This has everything to do with the brief flash of time we have to share with each other. Watch how a person can at once both change so much and still be themselves, who they are in their heart. The truth is at some point as we age we realize that we must set aside our anger and anxiety and arguments, and we seem to do so far too late in life. In the past year I’ve lost a half dozen people I loved very much who were my confidants and companions, and every one of them died relatively young, three of them in their early sixties. At the same time, my mother has nose-dived into a wall, fallen and slammed her head on a porcelain tub, fallen on the floor, faced cancer–again–had a pacemaker put in, battled neuropathy, and moved from her spacious condo where she lived with my dad, to an independent living apartment in Virginia Beach, to an assisted living apartment in Williamsburg, and she just keeps going. Last July she was in the hospital with pneumonia and sleeping eighteen hours a day, and the doctor did not think she would leave the hospital. Yesterday we went to lunch at an Italian restaurant and she woofed down a massive piece of tiramisu. She Just. Keeps. On. Going. And always with a sense of humor. She talks here about her move from Brooklyn to Long Island, from there to Virginia, and about how patient she can be. Or not. She sings the Banana Song, Woody Guthrie, a Shampoo commercial, and in one of my favorites when she had no idea I was taping from the cup holder of my car as we drove along, she sings “New York, New York.”

But this isn’t about Joan. This is about brevity. When we look ahead–when we anticipate–time can slow to a tragically slow pace. But when we look back, when we recall, we can transport our mind instantly to another era, as if it happened two seconds ago. This makes it seem like time goes by so fast. But it is the same now as it was when we were children. That’s the thing about time: it is dependable. Not one fat second will lose an ounce on my account. But the older we get, the more we recall instead of plan, so the clock can be deceptive. In these videos, Mom is full of energy, sitting up and laughing, with immediate recall of incidents an hour earlier as well as two generations ago; at the same time, here Mom is wearing oxygen, sometimes softly gasping for air, and her memory is nearly non-existent.

Time. It is the only measurement that matters. And we are endlessly distracted by the news and entertainment and the stress of finances and politics and health. But all of it slides away when we start to list what is essential. Then, the answer is easy: each other. That’s it. People leave us, sometimes slowly and sometimes with the swiftness of a cool, autumn morning that takes us by surprise. But they do, in fact, leave.

These videos are in no order, so one of Mom recently trying to remember her Uncle’s name might be followed by one of her looking stronger, heavier, talking about her favorite foods. I decided against a strict chronological order so that instead of watching a woman’s slow decline as age takes hold, we can see how life is, in the words of my friend poet Toni Wynn, “Paper thin.” I will add more to her page as time permits. Thanks for enjoying our mother’s beautiful sense of humor and simple take on what matters the most.

Note: There are some videos on the “Video” tab, but most of the videos are on the “Shorts” tab. Please check out both. And “follow” The Joanie Channel.