It’s that time again. When I was born Dwight Eisenhauer was president and Richard Nixon was his vice. The average household income was just over $5000 a year, the average house just about twice that and the average new care just about half.

I appear on the scene just hours after the first fifty-star flag had been revealed noting Hawaii, and a week before the Pulitzer Prize winning Harper Lee book To Kill a Mockingbird is published.

Benin, Niger, Ivory Coast, Ghana, all gain independence, and Aretha Franklin makes her first recording. Cyprus, the Central African Republic, and Chad gain independence. And in August, the Beatles with Pete Best perform for the first time with their new moniker in Hamburg.

Belka and Strelka board Sputnik with forty mice, two rats, and a rabbit and actually make it back to earth alive.

Hurricane Donna rips up the east coast and in my home state of New York, Governor Nelson Rockefeller declares September 19th Grandma Moses Day in honor of her 100th birthday. She was born at the start of the Civil War and died when I was a toddler. Time is deceptively swift.

I’m amazed by the people I shared this space with. First and foremost, birthdays remind us in fine mathematical style that we are alive and are still part of the population which constantly expands like bottle rockets in the deep blue sky. It bends my small mind to think of this reality that I’m certain everyone knows but few contemplate: I shared this planet with every other human who ever breathed the air. Read Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” as a brilliant reference.

Just in my lifetime: Mother Theresa. Malcolm X. Neil Armstrong. Jimi Hendrix. Pope Paul the Sixth. Lech Walesa. St. John Paul the Second. Thomas Merton. President General Eisenhower. Elvis. Pablo Picasso. Albert Schweitzer.

Rwandan Tutsis. The Lost Boys of Sudan. Steven Biko. Pol Pot.

I shared time with these people; these saints and sinners brushed my sleeve simply by sharing the earth during my stay. I have a loose connection to miracles and massacres.

This world has some serious issues; always has. It is at best, though, a hotel, and every once in a while I take a look at the register to remind myself who else stayed here. Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Mohammed, Ivan the Terrible, Ghengas Khan, all guests just over the slope of the horizon, just beyond some small slice of linear time. On the same human trajectory as mine but before is Geronimo, Moses, Jesus, think about the gentle bend of time, the careen of place that separates me from the disciples, the Visigoths, the founding fathers. All here but just before.

Closer to now, when I look inside the lines of my coming and going, I can see the souls who at one time or another shared with me this spinning blue wad. Not short of miraculous, we claim the same particles of stardust, and that’s what keeps me looking around when I walk down some city street; I want to know who on earth is with me on earth.

Time has ripped past. I was born a month ago. I waded through foreign rivers last month. My son was born last Tuesday. Fleeting. Swift. Impatient. And my thin life falls on the same graph as Richard Wright and Ernest Hemingway.

Carl Jung lectured during my youth, and Ty Cobb watched the same Mets players as me. When I was still cutting new teeth and outgrowing my Keds, I could have headed downtown with my Dad and possibly been on the same train as William Faulkner, ee cummings or Marilyn Monroe. I might have passed them on the street, maybe stood in line at some drug store counter with my mom and behind us because of the blending of circumstance might have been Sylvia Plath or Sam Cooke; Nat King Cole; Otis Redding. We have overlapping lives. On a Venn graph, we share the shaded space.

Judy Garland and I watched the New York Jets in Super Bowl Three. When I was born World War One vets weren’t yet senior citizens and World War Two Vets were in their thirties. Vietnam isn’t history to me; it is my childhood, my early teens. The fall of Saigon was announced over the loud speakers at my high school.

There are empty fields save monuments and markers where soldiers died defending this land against the British, against ourselves, and they stood where I stand and watched the hazy sun rise. Same sun; same beach, same blessed Commonwealth. Don’t mistake history for “back then.” Those people just happened to check out before us. It could have been us. It is us now, watching the orange moon like we do, noticing the calm river, sharing time with loved ones, thinking about others. Getting ready to die since it won’t be long before our lives overlap with the crying call of a newborn Einstein. Did you see that boy running at the park? That girl climbing the tree at her home? Did I just pass by some senator, some Cicero or Socrates, some St Augustine?

Like a couple today buying the same house that young lovers lived in centuries ago, like sour-dough starter. Like a relay race.

My adult son is trying to get a shot of fireworks in front of the moon, but the angle is wrong. When he was just five months old I held him with my hand over his ear, the other ear against my chest, as we watched fireworks out over the Atlantic in Virginia Beach. That was last Friday or so.

What a life. How many times do we reinvent ourselves? How often do we stop in our tracks, get out of the rush and inertia of humanity pushing from behind, and let it all go by, catch the moon over the Chesapeake? Why do we so rarely rest easy in the love of those near and of those still far away when our stay in this world in our time is brief at best.

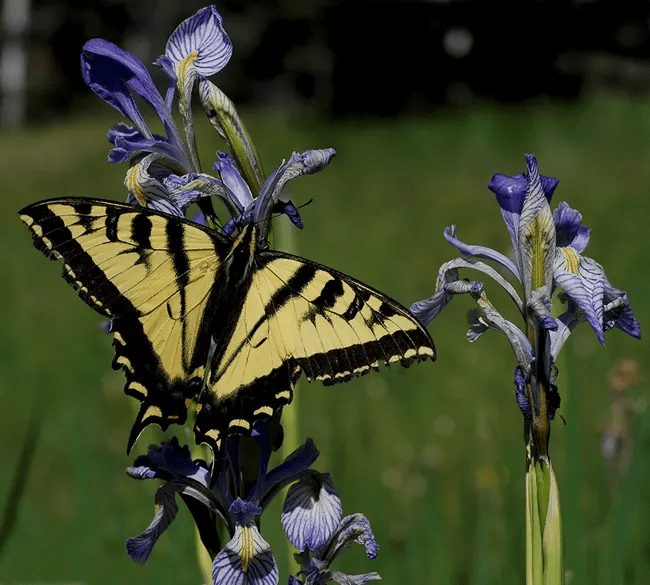

I love getting older, knowing more people, turning the pages. I miss my mom and dad, I miss Dave and Fr. Dan, and I miss Letty. My parents lived longer than I thought and the others I really didn’t think would check out as soon as they did. Thank Buddha for Ghosts and reincarnation. Just in case I watch the birds on my porch.

Listen, please: