I was in Prague when a Czech girl about twenty held a heavy sign outside a ticket booth. “Stop by the National Marionette Theatre for a Show,” it said. An arrow pointed up some stairs. She wore a clown suit. Ten AM, no later, she started—I saw her there four hours later, five hours, six, she stood supporting her sign and handing out leaflets to lead me to the “National Marionette Theatre’s Production of Don Giovanni.” I thought of the Statue of Liberty people hawking tax filing; and of giant chickens handing out coupons in the mall. This one is a national marionette theatre. This Czech girl pushed puppet shows on people.

Perhaps passing out flyers pays well. Or her parents preside over the theater, and this is punishment for tangling the marionette strings when she was five. Naturally, I couldn’t support such delayed abuse. I might have taken a look if this person in my path performed with a puppet or two. But no; she just stood there. Maybe she holds the heavy sign in exchange for free admission to any performance she prefers. Tonight, Mozart: The Marriage of Figaro. They’re puppets, though. I’m not easily fooled.

To be fair, exposure to these arts is rare and the ransom of holding a heavy sign eight hours a day in a clown suit is worth it. Still, when she handed me the leaflet, I declined. Taking it, I thought, would provide false hope of my attendance. Perhaps she’s paid per person, and upon entering we must say, “The twenty-year-old girl in the clown suit sent me,” and she’d expect her cut of my admission. That money, added to the rest from other guilt-ridden tourists, might be enough to buy the Bohemian bracelet at the boutique near Charles Bridge. She might, while on break, charge the jewelry having counted on money from her promised patrons. She would eventually pay for it knowing she had income from my gracious acceptance of her leaflet. But I pulled my hand away. You see, when the theatre is mostly empty, and puppets bounce to Swan Lake, she might notice my absence, my lie, my blatant mockery of the marionette art form. I could not walk along Karlova Avenue again, not past that theatre, that clown suit holding that sign, in angst over her noticing me. I know no flier to this theater is handed out without strings attached. Especially if dangling from her wrists, beneath the puffy sleeves, I might hear the clanging of the bracelet still not paid for. I could not bare it.

So, of course, I didn’t take the leaflet.

Fliers about music, however, I accept. The string quartet playing Pachabel and Vivaldi at St George’s still stirs in my mind, or the symphony at St Martin in the Wall. One student once stood between me and the Literature Café after I had been teaching and was thirsty. He pushed Bach on me, motioning toward some small space in the next building. Outside a cello player performed for free, teasing us, baiting us without charge so we’d get hooked and go for the harder, move complicated compositions inside. Good marketing, I thought—the whole Literature Café crowd could conceivably fill a concert hall for Bach. Still, I declined and tried to glide around him.

Unfortunately, leaflet pushers in Prague promote their papers to blind eyes, throwing themselves in harm’s way to deliver the news, the message, the memo that something is about to happen that simply can’t be missed. I see smoke rising on cold evenings from the myriad chimneys across the rooftops and imagine these Czech people, instead of going to the show, walk the streets and collect leaflets to burn for warmth at night, the ashes of theatre and museum bills billowing into the cold Czech evening air.

Hawkers hand out leaflets for museums, tours to other cities, walking tours of the castle, Kafka’s Castle, Havel’s castle; walking tours of the Golden Way where Kafka wrote in a small blue house, walking tours of the Jewish Quarter with its cemetery of headstones strewn about like fliers in a parking lot on a windy day. Leaflets of art museums in Old Town near the atomic clock, tours to the Golden Tiger where Hrabal drank beer and wrote novels; sheets of paper promote discounts at restaurants, coupons for strudel, Monrovian wine tasting, and more music. No guidebook is needed for Prague; no online sources recommending what to do on a Tuesday night in March. Just walk up Karlova Street, or Nerudova, and flier clowns keep information flowing like hot wine in the Bohemian cafés.

One guy one night one year handed me a leaflet for a pub he said was near, right around the corner, an Irish pub, and the next night was St Patrick’s Day, and if I walked that way with him he’d tell me what to order, what foods are best, and if I took the flier with me, I’d get a discount and he’d get paid, and I knew then I was right in not taking that clown’s flier, that she, too, depended upon commission. So this guy walked with me that March 16th, late, through tunnels, up steep streets, and half-way up one narrow medieval way was an Irish pub, and I relaxed, no longer worried about being led into some torture room out of some Tarantino film. I walked in grasping my flier, had Guinness and potato cakes when a large Irish man invited me to his place for a St Patrick’s Day party the next night. “His place” turned out to be the Irish Consulate, and there turned out to be a few hundred people. We drank beer and listened to the Chieftains and to rare Van Morrison, and to the Wolfetones. We ate and laughed about Dublin versus Manchester United, which I had seen in a pub after someone handed me a leaflet for happy hour to watch the football match. The ambassador talked about his love of Prague and one of the guests talked about the cathedrals, when everyone began to talk about the music, and that flier brought it all home for me; the spontaneity that fliers provide. Guidebooks usually are married to planning or at least engaged to thinking ahead, but the almighty flier with its primitive shoving into our faces while heading somewhere else is the ultimate in tangents, the epitome of carpe diem. This is, after all, Bohemia.

“Here’s a flier—do it now—don’t think” is what those hawkers truly hail.

One guy gave me a flier for a free strudel. I don’t turn down free anything, particularly food, particularly strudel. It was warm, with ice cream, and a pot of Irish Crème Tea, and I know the purpose was so I might purchase the pot of tea. Okay.

It is the unanticipated beauty of the immediate. It is the hard left turn. It is the unexpected now when moments of “what’s next” so often occupy our present ones. Sometimes life should be more akin to a pinball game: Instead of pulling our hands in, away from the tugs and tears at our sleeves from friends offering a last-minute road-trip, or family who knock unexpectedly, we should reach out and grab the opportunity. In Prague passing out leaflets prior to the Velvet Revolution indeed meant possible prison and accepting a flyer likely the same sentence. Indication of how important those fliers can often be. The power of the 8 1/2 by 11 sheet of paper can be immeasurable.

But more than that, they remind us that at any given moment, if we take our hands out of our pockets, we can discover a whole new train of thought, turn a whole new unanticipated direction. Little in our lives is designed for spontaneity; no, instead grand design proves itself with calendars, schedules, voice mail reminders, alarms and wake up calls. The places promoted on fliers are most often in back alleys or misunderstood. They’re the commoners’ billboard.

Once out near the Strahov Monastery, a dirty young woman with a dirty young child lay in the dust and filth of some alley not far from a nice restaurant where I used to drink fine wine, and she handed me a flier written in Czech. Her todler sucked on the crusty edge of his shirt. A passing stranger told me the flier read “Give me some money please. It won’t change your life but it might change mine.”

I did. It did.

Leaflets have been around probably since Gutenberg. But as a means of persuasion, they most likely hit the mainstream during World War I when the British air-dropped leaflets throughout France to communicate with the German army. The Nazi’s dropped anti-Jewish leaflets during the 1930’s and the early part of the 1940’s, Lee Harvey Oswald handed out pro-Cuban leaflets, and just before the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States showered Japan with more than five million leaflets warning the citizens of the imminent attack. It began, “Read this carefully it may save your life or the life of a friend or relative. In the next few days some or all of the cities named on the reverse side will be destroyed by American bombs.”

The Velvet Revolution in Prague in 1989 gained momentum behind the guidance of then play-write and eventual president, Vaclav Havel. The movement gained so much support, however, they couldn’t meet in the streets anymore and designated the Magic Lantern Theatre as their headquarters to organize. The dancers—out of work for the strike—would run leaflets around the city. It was from there propaganda flowed. They passed out bread, they collected money, and they made and distributed leaflets to gain support from students and workers alike under the guise of the theatre.

So naturally while contemplating the clown at the National Marionette Theatre, I rethought the whole puppet thing; maybe I was wrong to walk by so fast. If she did get a cut, and I did attend, then she’d be happy, her bracelet paid for, and I’d attend what might turn out to be an amazing performance of Don Giovanni, albeit by sophisticated Pinocchios. So the next morning I vowed to go. Perhaps my attendance also supported some revolutionary agenda, even if her own. Clearly, it’s happened before.

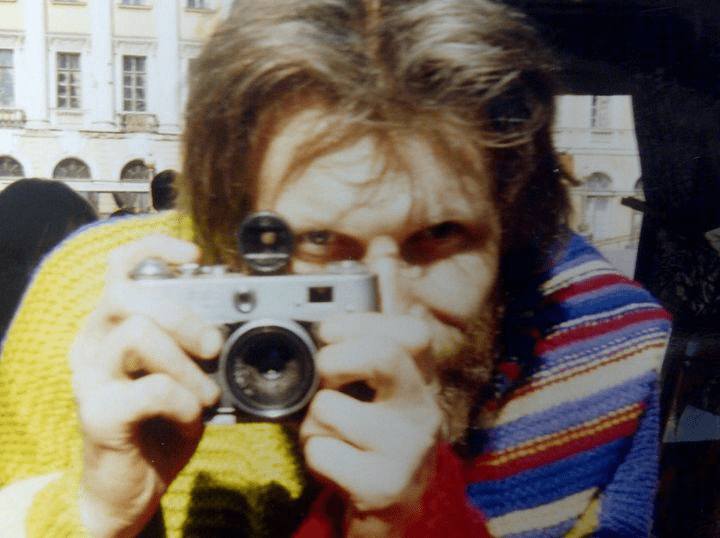

The next day at the foot of the castle steps a man gave me a flier for the Torture Museum. “Just tell people to walk up and down these stairs,” I joked, but he didn’t understand. I walked across Charles Bridge, up Karlova, and looked for the clown. The twenty-year-old was still there, and I walked close enough for her to hand me the paper.

Don Giovanni, or Don Juan, was written by Mozart and he first performed it here in Prague; Casanova himself collaborated on some of the scenes. In fact, in imagining Don Giovanni, Casanova said, “My life’s been filled with adventures, and truths often become larger than life when they’re retold. I never correct the tales that are especially hard to believe. It would be unkind to those who want to believe in them.”

Sometimes you just need something to believe in.

I sat in the back and enjoyed the marionette show. It was only later I realized I never saw a single string, not one wire.