The following is the longest blog post to date at A View. It is the result of news today that going to Russia is dangerous even for Russians with dual-American citizenship. I miss the place, the people, the endless laughter and outrageous stories from decades of travel. The country has come full circle in that time. For anyone wondering what the hell happened, here’s what happened:

The Russian Arc

In 1994, the streets of St Petersburg were dank, a monotone of browns absent of advertising, neon, or anything other than some Soviet style atmosphere. The only placards placed in random spots on Nevsky Prospect—the city’s Fifth Avenue—were Marlboro signs, the only western clothing of note worn by the suddenly displaced masses was Adidas warm-up suits. It appeared a parody of itself as presented in 1970’s and ‘80’s anti-Soviet movies. For seventy-five years the country, and Leningrad, moved in darkness under the Soviet leadership, and for centuries before that under the long reach of the Czars.

But in 1994 when I first arrived to teach American culture to faculty at Baltic State University, the first of what would end up being more than twenty-five trips in thirty years, democracy had found the streets of Leningrad, which had just changed its name back to the Imperial “St. Petersburg,” and Russians struggled to figure it out. The first week there, I stood in line for two hours at a bakery, and when I pointed this out at the college, my colleagues shrugged and said, “Da. Canushna.” Yes, of course. I explained that in the States, a new bakery would open across the street and be faster, charge less, offer discounts. Then I had to explain discounts and why, explain that the cashier who stood outside smoking while twenty people were in line would be fired. This led to a conversation about capitalism, and everyone was suddenly enthralled to hear about businesses and learn how to make money, the advantages of choices, the value of options. The men of the previous generation on through to the college students present when I first taught in the city, simply understood service to their country as paramount; it involved time away from family, but also provided pensions and a chance to protect their living conditions.

But after the coup, and certainly in the few years which followed leading up to 1994, it was a brand-new way of existence, and the long, cold winter of communism had finally ended. Things changed—and this is where it got tricky. At first everything was different overnight, like their currency, living conditions, international relationships, and availability of goods. But then the changes slowed to an immeasurable pace. People couldn’t find jobs or food, or they had to work for some organized crime group. Old folks lined the metro begging for money or selling items—shoes, loose cigarettes, empty bottles. But within a few years they figured it out. One afternoon that first year I went to the market behind a cathedral in the arts district. It was a park area with tables covered in tourist items: matryoshka dolls, the famous Russian wooden bowls known as khokloma, pins, small wooden toys bears. Scarfs, shawls, icons, amber jewelry. The following year the market built small booths in long rows instead of random tables. A year or two later, the booths had roofs over them, then lighting was put in for night shopping, and by the 300th anniversary of the city in 2003, the entire market was covered, gates out front, a veritable mall filled with all the previous items, but also fine art, expensive purses, technology, and food were added to the shelves. The Russians were figuring it all out, and many made more money in a month than they had in a year under the Soviet regime. Organized crime groups took over and took a cut, and the city streets once filled with just Russian-made Ladas were now lined with black SUVs.

A friend of mine in the marketplace, photographer and artist Valentine, remained my source of all things business, and the changes almost became too much for him to handle. In 1995, I went in the Catholic Church nearby to find piles of rubble where an altar used to stand eighty years earlier, and the walls had been painted black, on the floor lay statues without heads. The priest, Fr. Frank Sutman, explained it had been used as a storage facility for motorcycles since the Great Patriotic War, World War Two, but the church took it over for the first time since 1917. By the turn of the millennium, the grandeur of the marble floors and beautiful walls had been restored. Across the street was a small shop. In the early years, I had to point to the item I wanted on the shelf behind a counter or in a glass case, and if I liked it, I took a handwritten receipt to the cashier who figured out the total on an abacus (no kidding), gave me a new receipt which I took back to the first worker to retrieve the items. This is how it was in the few grocers, the pharmacies, the bakeries. Only in the tourist market did one deal directly with one person.

Years pass.

A supermarket opened with cashiers at the end of conveyor belts who rang up your items, bagged them, and you walked out like you just left Walmart. The discovered calculators, paper bags, and the shelves were stocked with European goods. And on the streets, neon signs dominated the avenue: KFC, McDonalds, Pizza Hut, clothing brands, cigarettes, alcohol, appliances, cars. Except for the language I could have been in my native New York. The once empty streets were filled with people, all on their new phones, all taking pictures, all donning expensive jackets and shoes.

These were the years of tourism, of an entire generation and the next growing up without memory of Gorbachev, even of Yeltsin. We went on canal rides and took videos, wandered through neighborhoods and graveyards. I went to Victory Day a dozen times, talked to Vets of the Great Patriotic War, who loved to share their experiences, and I talked to the women—St Petersburg became known as a city of old women since the men mostly died in the war and children starved to death—about the changes, often as they swept the streets with brooms made from birch branches.

We went to the Kirov Ballet, the opera, folk shows, and soccer games. We dined in restaurants from Germany, Italy, China, and played music, danced and drink at The Liverpool, a Beatles bar.

Peter the Great’s dream of a city of culture, his “Window to the West” as he called it, had come to fruition.

By 2014, after twenty-years of going to Russia, anyone thirty or thirty-five years old and younger only new this new way of life. The very notion that the government would dictate what they could and could not do was as foreign to them as it is to us in the west. Students graduated from college and set up businesses, tech companies, they traveled freely and often to Portugal, the United States, Hong Kong, Sicily, everywhere. After almost a century of needing to walk everywhere and live with two other families in small communal apartments, they now owned cars and nice apartments. The once common practice of tourists bringing Levis or other western brands to trade for Russian trinkets was not only over, but laughable, with malls opening up with shoe stores, clothing stores, phone, sporting goods, and music stores, all filled with western brands.

The “old country” of Russia had so modified over the course of just two decades, one had to be in their forties to remember the Soviet system. What the average Russian citizen could not know, of course, was that the modifications made in palaces throughout the country, but in particular St Petersburg, was paid for by organized crime to increase tourism and international trade. The city where I could in those early years buy items for a few dollars, quickly figured it out and charged twenty or thirty dollars for the same items. Restaurants appeared everywhere with prices for those driving the SUVs, not for the Lada crowd.

My friends from Russia adjusted. A tour operator learned business well and built a company that dealt with tourists from all over the world. My artist and writer friends found new freedom in being able to take pictures of anything and anyone they wanted without recourse. They criticized the Yeltsin administration without worry of harm. For seventy-five years, the notion of dissidence, which not only included those who wrote against the government, but those who simply didn’t always write positive things about the government; particularly Stalin, had in just a few shaky years, slipped into history. Going to St Petersburg became simple. There was even talk for a while of dropping all the VISA requirements. I wouldn’t call it democracy, as such, but communism was dead. Gone. Lenin’s statues which had been everywhere in the early ‘90s were much more difficult to find. It became simple for a Russian to leave home and travel to the United States. And the did, gladly, relishing in being a part of the world, finally. This wasn’t simply détente; this was the start of a beautiful relationship.

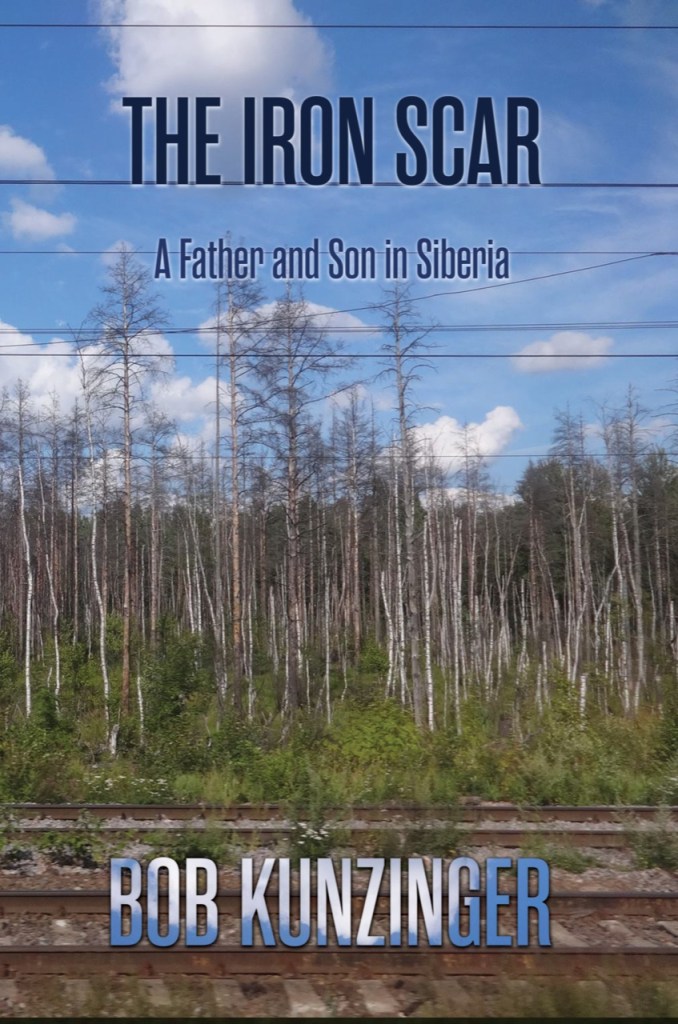

In 2013, my son and I rode the trans-Siberian railway from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok, across more than six-thousand miles, and seemingly across decades as we retreated into the previous century the further east we traveled. In Yekaterinburg the western influence was still obvious, but in Irkutsk, another few days east, Soviet style practices still appeared common. The one fortunate thread remained the people, all deeply rooted in new democratic, even capitalistic practices. They drove Kias and Toyotas, they wore Levis and Ray-Ban sunglasses, and they spoke of their vacations in Australia, the Canary Islands, Florida. If I had not been already in my fifties, there would be no basis of comparison to the old, Soviet ways I grew up learning about, fearing, hating. Nothing I had learned about these people was true, even in the early nineties. The propaganda machine, practiced just as efficiently in the west, had turned out to be shallow, and that was with a generation of Russians whose experience had only ever been Soviet or Czarist. This new generation, those already well into their careers, families, homeownership, and substantial investments, just two decades old, was the dominant population across the country, and they knew less about living under a fascist regime than I did.

Until Putin.

He came in early and soft, almost friendly, certainly acceptable. He was a man with a vision for this new country who followed the floundering Boris Yeltsin, and as Putin’s power and wealth increased, he rebuilt his native St. Petersburg. He saved the former Soviet Union from ruin and the economic disaster of the Yeltsin years, which left a rampant homeless and starving population to fend for themselves. Right after the coup to end communism, the nationalization of all businesses and housing ended, but so did the pensions. Housing privatized and if the residents couldn’t afford the new rent they were kicked out. Hospitals quite literally rolled patients out the door and left them near churches to fend for themselves. Putin moved from the city’s Vice Mayor up the ladder to President on the promise he would “clean up” the homeless problem, “employ” people willing to work for anyone, and made business deals that brought unprecedented wealth to the nation. Russians welcomed him; so did western leaders. And the population which benefited the most were under forty, tech-savvy millennials who worked their way up, drove expensive cars, and lived in large sweeping apartments on Nevsky Prospect with beautiful dachas in the countryside or Ekaterinburg. Tourists who visited St Petersburg discovered open palaces with gourmet dining rooms, clean hotels with five-star service, shops with icons, malachite and amber jewels, and all-things-fashion. Russians, too, became tourists able to see more than the dachas they shared with other families. They traveled to Italy, to Portugal, France, and the United States. Satellite television common in the nineties became fast internet service enabling partnerships and communication with anyone anywhere.

Then Ukraine happened.

Those same students just out of communism and thrust into capitalism are now in their late forties, at least, and their children, raised in nothing but a mostly free-capital society with all the advantages and freedoms we understand here in the States, are being drafted into an army to attack a country they spent their entire lives visiting on vacation. When the news speaks of “Russian military,” this is who they’re talking about; men and women whose only reference and background was freedom of choice, of employment, of wandering, of economic wealth. Their only requirement was the possibility of two years mandatory service before they turned twenty-seven. Piece of cake; their billets ranged from one end of the earth to the other. So while their parents may not have been surprised to have been called to service in Afghanistan in the seventies for the Soviet government, these men and women dreading duty in neighboring Ukraine had anticipated their best-laid plans to pursue personal ambitions, and went to schools which had been teaching them international relations and economics, until the hope they had for life was disturbingly aborted for reasons beyond their comprehension or desire.

Then western sanctions hit and the country shut down, banks stopped all business outside the borders, foreign companies which lined Nevsky Prospect with signs and tables and parties were suddenly gone. The streets once again seemed grey, empty of life. Employment disappeared and no pension waited by to save them, so the army promised to pay their bills, which they did for a short while, and when word spread that the truth is they could barely feed their soldiers, let alone pay them wagers a fraction of what they had been used to, many fled.

Back in the mid-nineties, a friend of mine would write complaining about Yeltsin, about the lack of support from the United States, about the homelessness and difficulties dealing with “Old Russians,” who knew Soviet Ways, and how the “New Russians,” assume they have a right to whatever they can get. The anecdote which circulated then was how a New Russian in a Mercedes SUV waited at a stoplight when an Old Russian in a Lada with no brakes hit him from behind. The Old Russian got out of his car terrified, but the New Russian simply said, “Aren’t you glad I’m here to stop you? Otherwise you would have run out of control and killed yourself.” That was the propaganda which took hold and brought this nation to life; this nation now isolated and quite possibly on life support.

In the last few months, after a year of no word from friends who still live behind this new Putin Curtain, I heard from the friend who twenty years ago spoke openly of the problems in the city, back when the place was starting to shine. This time he speaks only of pleasantries, of how beautiful the weather is, and how he loves his city. No word of Putin; my friend remains uncharacteristically quiet about all things governmental. Another friend in Europe tells me his own family in St. Petersburg reports the lines are back for the purchase of many goods, like before the coup thirty-five years ago, and families are once again forced to move in together to save money, and he cried knowing his family whom he could visit whenever he wanted and who came to see him often, no longer has the ability to travel anywhere, nor the means even if they could leave. And he spoke as if this was the early fifties and Stalin was still in charge, that “to speak negatively about President Putin is to be thrown in jail.” And today come reports that anyone with dual citizenship with the US and Russia who had been contemplating going back to Russia should not do so lest they be detained indefinitely in Russian “holding” areas.

Maintaining control over the population of the Russian Empire after the Civil War following World War One was not difficult; the people had never truly known freedom as we understand it; Czarist Russia ruled for nearly a millennium. Russians appreciated the promises made by the Bolsheviks, and despite many of those promises never coming to fruition, most people abided by the Soviet system, even out of fear. And following the fall of communism in the late eighties and early nineties, Russians welcomed the opportunity to break free of the limitations of their previous government, but when almost a decade passed and things got worse, not better, it was not difficult for someone like Putin to convince them a little more government control, “like it used to be,” was a good thing. For a while, he maintained a perfect balance of top-heavy government—albeit one on the take to the tune of billions of dollars—and the personal freedom to come and go, grow and expand, as one pleased. This lasted until February 24th, 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine.

But something is different this time. One hundred years ago the people had only known an oppressive government, as was the case thirty-five years ago, so leading them down the path the new leaders desired was not difficult. But now, two generations into a country used to most of the freedoms we have in the west, the population, despite the Russian propaganda to the contrary, is displeased with their government’s bombing of an innocent nation, ending the freedoms of the people of both countries. When the war began, Russia had 360,000 active troops. In the past two years, 315,000 of them have been killed or badly wounded, only to be replaced by new “recruits.” According to the UN, that amounts to 87% of their numbers at the start of the war. In the Ukraine since the world changed two years ago, more than 30,000 soldiers and civilians have been killed or wounded.

The Russia I knew is dead. I miss my friends, Valentine, Igor, Sasha, and Dima the violin player. I miss the atmosphere, the storied example of perseverance that was the St Petersburg I knew, filled with veterans who miraculously survived the siege of their city for nine hundred days in World War Two; a siege and destruction of people which one of the city’s own, Vladimir Putin, once exclaimed must never be allowed to happen again, until he did just that. The promise and beauty of the Russian artists, the teachers, and the children, are simply gone. And in Ukraine with a history deeper, older, and more beautiful than even Russia’s, a civilization has been annihilated. Historians will not point to a myriad of reasons for this incomprehensible tragedy; studies will not have to be undertaken to better comprehend the causes of the invasion. The brunt of this brutality falls squarely on the shoulders of Vladimir Putin.