For some years now I’ve spent time toward the end of December thinking about the significant moments of the year, which can often include some tragedy, of course. But I quickly became a fan of this wide-lens scan of the previous twelve months. It helped me focus on moments that meant something instead of memories just bouncing around my brain, turning them into little more than some passing haze between other, seemingly more important hazy thoughts. It didn’t take long to figure out that those five significant moments truly were the most important days of the year, and they deserve a more intense recollection. So I listed them for myself and thought about them, focusing, concentrating, then almost reliving them. Yes, even the sorrowful parts.

These are the five that emblazed themselves into my mind so that even just a brief touch of an aroma might bring back the day with complete clarity.

Gwynn’s Island, Virginia. Michael submitted a few pieces to a juried art show at the Island’s museum, and as a result he had to make several trips there to drop off the work, to go to the opening, and then to pick the work up after the show, so I joined him. We hiked the beach one time and ate at one of our favorite Mathews County places, Richardson’s. It is always relaxing when we go on one of our hikes through the trails or along the various coastlines of the area. On that day we dropped off his work and discovered the hidden gem of a museum with artifacts dating back to John Smith’s sojourn there and his storied subsequent swim in the Chesapeake not far from here, where he was stung by a stingray, giving the point its name. But the second trip there was most memorable as the turnout for the art opening was excellent, and they set up an excellent table of food and wine, while the artists and guests admired the work. An art historian and teacher sat as judge, and Michael’s work won first place. Her explanation of her choice was touching and as an art appreciation professor myself, I truly admired how well thought out her choices were (this isn’t Dad speaking, really). One of his rewards for first prize was a gift card to the popular local joint, Hole in the Wall, where we ate on our third trip down. This all seems fast and so local to rank as one of the five moments of a year, but it is hikes like these, combined with the display of his work, that brings such peace I cannot find many other moments during which I’d rather spend my time.

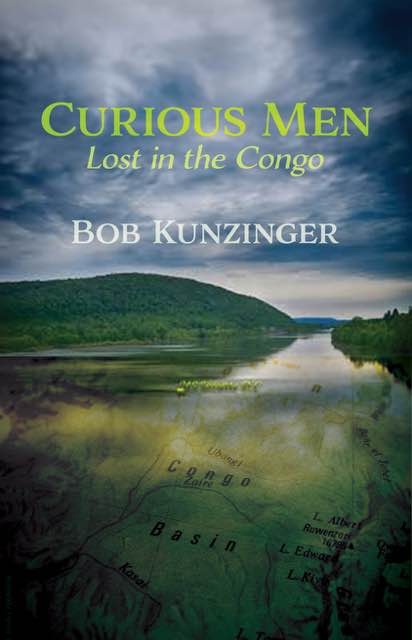

Curious Men: Lost in the Congo. While the official release date for my new book is not until January 4th (as that is the birthdate of the subject of the book), it is available already and receiving the copies in the mail meant more to me than my other works. This one was very personal, and it had been a monkey on my back for forty-five years. The work has been through so many versions, I cannot honestly tell you the final version is the best one, but it is the one that I believe works best for me now. In the end, I discovered the book was not about me and not about my friend. It is about trying to figure out life when out on your own for the first time, and what we choose to pay attention to and choose to ignore. What is most significant about this work and the release of the book is this one is the first book I’ve written which was done so entirely for me. I wasn’t thinking about audience, about others who knew the story, not thinking about critics or publishers, editors or bookstore owners. It was for me. It is the most honest thing I’ve written, and I still could have taken five more shots at it and not been completely satisfied. Releasing this book has more significance than I could ever possibly convey (and it is doing very well thank you very much).

Spirit Lake, Utah. Okay, so this one is special. We drove up in June to an area where snow still drifted across the trails and the temps at night fell into the low forties at best. No running water, no electricity, a wood burning stove in a cabin the size of an SUV, with a firepit off of a porch out front. Our cabin was “Sacajawea,” and we left it often to walk down the hill to Spirit Lake, lay on the dock and watch the stars, or more often to hike some of the trails climbing above 11K feet, where a few times we saw moose. Rarely in my life have I been that relaxed, that detached from everything which causes stress, and able to say what I wanted and talk for hours without any thought about how it came out. I was never so present. How often do we find ourselves so much in the present moment that all matters of concern slide away? It happened that entire trip.

The Netherlands. The only tense moment of this trip was at the end, when I was returning the car to the rental lot at the airport, and I accidentally left the airport and found myself on an interstate headed back to Amsterdam, and a sign which read, “Next exit 14 miles.” I texted to say I’d be really late getting through security, then I sped, spun about some cloverleaf, slipped into the rental lot thirty minutes later and tossed the keys to a man who wanted to inspect the car. I took off running and panted my way through security. The rest of the trip was perfect. To walk the fields where Van Gogh walked and painted, to stay in an Airbnb just a mile from where he lived with his parents in Neunen, to dodge bikes and cars in Amsterdam and stumble upon a festival in Volendam. I will say here that I had a blast, laughed endlessly, remained silent for hours without worry of the quiet, and wondered

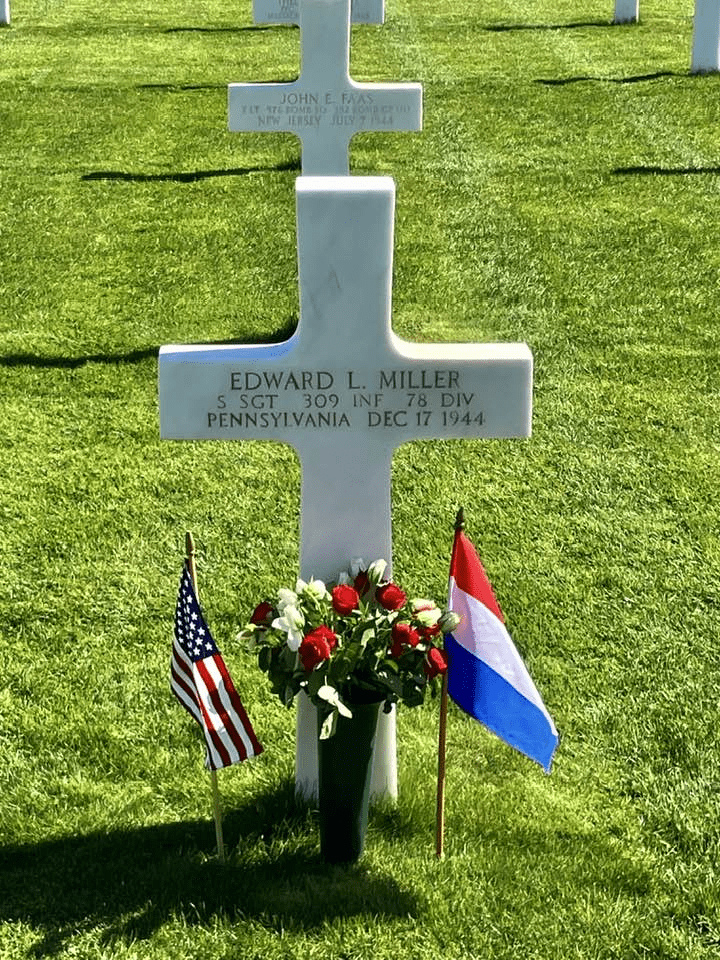

beyond words what circumstances found us there with such presence of mind. There was the small village where a stroll into someone’s backyard yielded a take of water buffalo cheese and yogurt, and I met my new friend, Sparky the Water Buffalo. An old woman in a housedress came out to her own barn where we looked in cases at water buffalo ice cream and other items, to sell the goods without a word of English. By far, however, the highlight of the trip was a small ceremony for Staff Sergeant Edward L. Miller of Pennsylvania who died on December 17th, 1944, at the Battle of the Bulge, and where I stood silent while his niece rubbed sand from Normandy in his name, made an etching of his stone, and met the family who has taken care of his grave since the war. While they spoke to each other, I looked about these grounds of the American Cemetery at Margraten, at the more than 8000 fallen soldiers, and said to one of our hosts, “These men were no older than my students,” and the weight of war, of the Miller family’s loss, of this memorial journey across four thousand miles settled in my chest. What an honor to be part of this in a small, outside way. I can still smell the freshly mown grass as they were cutting it while we stood nearby. I can still hear the voice of the young woman at the park who spoke with such respect and honor. What a day. What an incredible trip. I’ll leave off the part about driving in Delft.

Mom. On April 12th my Mom, Joan Catherine Kunzinger, died at almost 92 years old. Joanie was the smartest, most honest, most caring, most loving woman I have ever encountered. Her strength as a young girl who had to take care of her siblings, as a young bride with two and then eventually three kids, as a wife taking care of Dad when he was not well in the last years of his life, and as a widow who hauled herself around absolutely always laughing, appreciating the fact she was simply alive and grateful. That is the word for Mom: Grateful, for everything, She could make friends with a lamppost and everyone I’ve ever met who met Mom, loved her. Her solidly Irish and Italian background came through strong, and she was forever a New Yorker. But Mom was at home wherever she was. I was fortunate enough to make more than fifty short videos of her talking about her life, but I cannot watch them without breaking down. Still, here’s the significance of her being on this list this year: She wasn’t expected to die. Not when she did. The day before I left for the Netherlands, I made a video of Mom in which she recites a poem about tulips, and laughs. I promised her I’d

bring her cheese, and she was very excited (despite her predictable “oh please don’t go to any trouble” comments). Two days after I returned but was still at my sister’s home in Pennsylvania, Mom fell while getting up from Bingo, and she hit her ribs on the chair. She never recovered as her paper-thin lungs were already beyond strained. I made it home in time for her to look in my eyes while she lay in her bed. Her eyes swelled a bit when she saw me, but she quickly fell back to sleep. She died that night after I had driven home.

But here’s the thing about this: I have in front of me a picture of the family the morning after the funeral, and we’re on the boardwalk in Virginia Beach, clearly and appropriately enjoying each other’s company, just as Mom would have wanted. My sister made a comment when captioning the picture about this being “Mom’s legacy.” That hit me well. There is her life, right there, in the three kids, the five grandkids, the five great-grandkids, and it’s only just starting. Mom taught me through example to appreciate just the reality that we are alive now, but not for long, so we must love. I never got to tell her all about Amsterdam as she was very excited about me going and was looking forward to hearing about everything. Instead, I ate her cheese. She would have laughed at that.

The days Michael and I spent at New Point Comfort before the art show, the narrative of Curious Men and why it means so much to me, Spirit Lake, the Netherlands, Mom—all of these are the most significant moments of the past year because of the people; only because of the people.

I hope from now on when I recall events from my past, I recall them solely because I had the chance to love and be loved and let that always be what I remember.