Sure, some of you will tune in to watch the Apple Drop in Times Square, if it is, in fact, dropping this year. In fact, throughout New York State, balls drop at midnight. But some of us prefer the big bologna drop in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, while others tune in to the Peach Drop in Atlanta.

But if you prefer to go to sleep early, catch the Lego Drop in Winterhaven, Florida, at 8pm. At Sloppy Joe’s in Key West, a giant conch shell drops to the bar, while in Indianapolis they drop a car. Honestly, a car. In Easton, Maryland they drop a crab while in Havre de Grace, Maryland they drop an eight foot by five foot foam, illuminated duck. In Hagerstown, of course, it’s a donut. In Pensacola, Theresa will be watching the Pelican Drop, while in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, I fully expect both my friends Barbara and Sean to watch the Peep Drop. It should be pretty quiet.

In Beaufort, North Carolina, they drop a pirate, and in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, much to their…they drop a ball of popcorn. In Dillsburg, Pennsylvania, just ten miles from where I used to live, they drop two pickles, while in the capital of Harrisburg it’s a strawberry. I have no idea why. My cousin Ed said his head will drop on the pillow in Austin just after midnight, whereas Toledo will weigh in when it drops its Cheese Ball. In Boise they’ll drop their new Glowtato–a potato internally illuminated, of course. My favorite, however, is in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where they drop a 19 foot illuminated chrome chili pepper.

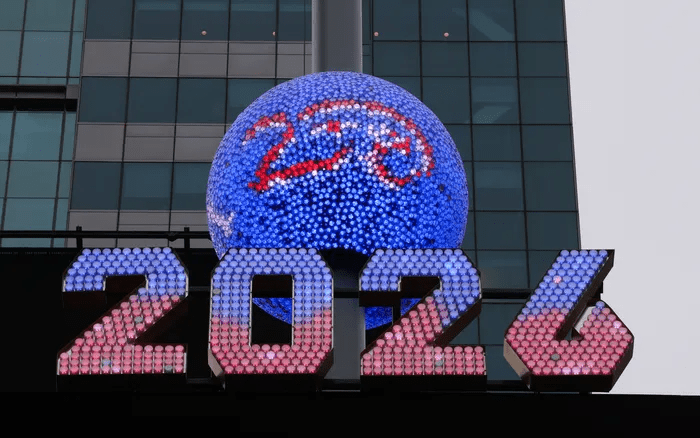

The whole notion of dropping the ball in Times Square began in 1907, organized by Adolph Ochs, owner of the New York Times, with nothing dropping at all in 1942 and 1943 due to “dimouts” during the war in case of invasion. Instead, attendees spent a moment in silence for the fallen. This year, the ball which descends at midnight is more than twelve feet in diameter, has a surface of crystal panels made by Waterford, and contains roughly 32,000 LEDs. But this year for the first time ever, there will be two balls (have at it late night hosts). The second, which will begin to fall at 12:04 am, is red, white, and blue to commemorate the 250 anniversary of the country.

It’s definitely a night to drop things. We drop hints about things we want and a few pounds as part of the new resolutions. Plenty of people in the entertainment industry use this significant date to drop their new album, their new book, their new movie, their old boyfriend, and the occasional dime bag.

In the old days neighbors would take it upon themselves to drop in and wish everyone a Happy New Year, while relatives are likely after a few more rounds to drop the charade and tell us how they really feel, and we’ll argue and argue until one of us, finally, says, “let’s just drop it.”

I’ll be outside as well, at the river, watching the nearly full waxing gibbous moon wash over the Chesapeake and it will take my mind off of the passing of time, the coming of the New Year, and the spinning of the earth like a ball, like a top, like a “tiny blue dot.”