Jan Weiner (left) and Arnost Lustig

Portions of this piece originally ran in Ilanot Review as “I Knew Two Men,” and it has subsequently appeared in several journals, including a publication honoring the late Arnost Lustig.

My son is leaving for Prague in a few days and this is on my mind.

Prague Adaptation

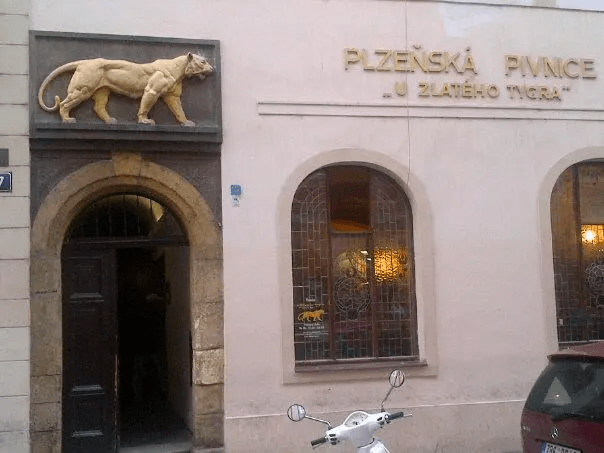

Arnost Lustig and I drank pilsner at the Golden Tiger in Prague. A large man in a white smock served our fourth pint when I asked about Hrabal. “You knew him, then,” I said.

***

“Yes, of course. We all knew him. The writers, the musicians, we all knew each other.” Arnost leaned forward. “Prague’s not that big, you know,” he said and laughed.

Arnost was a burly man who wore a leather coat and carried a satchel. We sat one table down from where Bohumil Hrabal, the great Czech writer, once drank. Hrabal came here to enjoy his beer and tell stories which ended up as classic works of European literature, such as I Served the King of England and Too Loud a Solitude.

“He came to Washington and stayed in my flat once,” Arnost added.

After a while I mentioned Hrabal’s death.

“Okay, then, let me ask you,” I leaned into him so the gatherings of Czech men at this mostly hidden pub couldn’t hear. “Do you think he fell out of that window like the nurse reported, or did he jump?”

Arnost leaned back and laughed. “Ah! Such mysteries we can’t answer! How we all love unanswerable questions!”

“She said he was feeding the pigeons. At a hospital? Come on!”

Arnost smiled at me while ignoring my comment and continued to talk while he said hello to some patrons. Everyone knew this man. “So yesterday you went with Jan to Terezin. Tell me about it.”

The day before I had walked about the Terezin Ghetto with Jan Weiner, a colleague of ours. Unlike Arnost, Jan was a stern man with a straight back and fine combed hair. He was calculating. He didn’t turn his head to talk but his entire body instead, like a soldier always at attention. He was very proud of himself, and every conversation somehow reeled back to his accomplishments during the war. To be certain, he deserved the praise, albeit mostly self-inflicted these days.

Arnost shook a stranger’s hand then nodded to me. “Did you sit on the cot?”

We sat on the cot.

Terezin is actually the so-called “town Hitler gave to the Jews,” for its use in successfully teasing the International Red Cross into believing the Nazis had set up the Jews well in small towns of their own. An adjacent eighteenth-century small fortress, used as a political prison for anti-Nazi protesters, is where Jan and I spent the morning, walking about the museum. Arnost knows Terezin well: he spent nearly three years there interned during his teens. He worked the rails that would bring him and his family to Auschwitz where his father was immediately gassed. On a transport to Dachau, the allies bombed the train and Arnost took advantage of the confused guards and escaped into literary history, writing countless bestsellers about the Holocaust and Terezin, all wrapped in the folds of unrequited love and the romance of war, despite its genocide. Diamonds in the Night, Night and Hope, and Darkness Casts No Shadow all remain staples of Holocaust literature.

So Jan and I walked into the women’s quarters at the Small Fortress, a compound really, and he showed me what one of the small cells looks like. We sat on a cot and he said, “Here, my mother was a prisoner. Right here.” He stroked the rusty metal and sat straight, stern, and oddly proud. “They tortured her for several days in every way imaginable before they killed her.” We walked about for an hour or so, and outside the compound he sat on a wall and ate a sandwich.

On the way back to Prague he told me that during the war his family took care of two young girls. Their parents had traveled to Africa as missionaries and were to return for them but the Nazis took over during the interim. “Those girls were gassed,” he said, then explained how soon after this his own father and step-mother killed themselves in their apartment in front of Jan. That’s when instead of giving up he escaped on a train south to Italy where he was imprisoned, only to escape to England. There he joined the Royal Air Force and flew bombing missions that helped turn the war. This was a real hero. Before we got off the bus in Prague we shook hands and he said, “I don’t believe in God.”

“Okay. I get it,” I said.

“No God could exist in a world like this,” he added.

“Okay.”

Arnost smiled and said, “Jan is always trying to convince himself of something. It makes him feel better about life.” He nodded toward a relief of Hrabal on the wall above the next table. “What do you think, Bob? Do you think you know what happened?”

Here’s what I knew:

Hrabal died when he fell from the fifth floor window of the Bulovka Hospital in Prague while leaning out trying to feed pigeons. He also lived on the fifth floor of his apartment building, which itself is uninteresting except for his fascination with fifth-floor suicides. He dreamt of his own death from that height. He would lean out the fifth-floor window of his flat to gaze up at the sky above St. Giles, and he would often walk down to the Maison Oppelt, where Franz Kafka once wanted to jump from the fifth floor.

I knew he sat here, six feet from where I drank my fourth pilsner with Arnost. They spent a weekend together in DC drinking beer and watching Charlie Chaplin films, right after Susan Sontag wrote in the New York Times that Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude would be “one of the twenty books that would shape literature in the twentieth century.” I asked Sontag once about Hrabal with whom she had laughed and drunk in New York City, and Susan said to me, sober as can be, that if I could only read the writing of one person let it be Hrabal.

And I knew that his devotion to his wife, whom he called Pipsi, was so complete that after her long, drawn-out death, he wanted to jump from their fifth floor window. “Every room in the apartment hurts,” he wrote, and every time he thought of jumping from that fifth floor he said his guardian angel pulled him back because the angel wanted him to “remain as yet. But I’ve felt like it.” Just like Kafka, Hrabal noted, who had also been “hurt by the world,” he supposed. Kafka didn’t jump from the fifth floor of the Maison Oppelt onto Paris Avenue, as he desired. I knew Hrabal was fascinated that, ironically, Rilke’s Malte Brigge tried to jump from another fifth floor in Paris.

And I supposed it was all too poetic for Hrabal to bear, like his beloved poet Biebl who jumped from a window to die only after asking a painter to create a canvas of a man falling backwards out of a window. So Hrabal’s routine included what he called “morning suicidal, work until midday, lunch, bus ride, back to the pub.”

This pub where one beer after another would fall backwards into his round and grateful stomach, and he’d listen to these very same men in this very same Golden Tiger talk, feeding him what he called “morsels of life,” which he’d store away and use later in his work.

Including Too Loud a Solitude, his very last work before his unfortunate fifth-story pigeon-feeding plunge. Too Loud a Solitude, where at the end the protagonist climbs into the trash compactor he ran for thirty five years beneath the streets of Prague and compacts himself, saying, “I will follow Seneca. I will follow Socrates, and here, in my press, in my cellar, choose my own fall, which is ascension.”

I thought perhaps Hrabal chose his own fall.

That’s what I knew. I stared through Arnost’s large glasses into his engaging eyes, which have witnessed what no human should, but who took those experiences and excised them through his enchanting and haunting prose. Jan never let go of what happened, whereas Arnost took what happened and gave it back to the world in bestsellers, some of which had been made into films. By 2003 he was so respected in Prague that his good friend, playwright and President Vaclav Havel, gave him high honors and an apartment in the Castle, yet his eyes looked the same as they did in the rare pre-war photos of him with his parents and sister.

“What do you think, Bob?”

I listened to the old men who sat at picnic tables which lined the pub walls and wondered if Arnost listened to what they said. Did he store away morsels of life for use in one of his works? What were these men saying that Hrabal might have half listened to and molded into prose the way only he knew how while beers tumbled all afternoon?

This was in 2000. Hrabal fed his pigeons only a few years earlier. These may in fact be the same men.

I nodded at Arnost. “I read once that he could recite whole chapters from books without missing a word,” I said. Arnost laughed and agreed he had heard the same thing and noted Hrabal to be one of the most intelligent men he’d ever known.

I stared at the room full of Czech men. “There’s really no way for someone like that to make a graceful exit, is there?”

Again Arnost laughed. “Nothing poetic enough you don’t think?” He thought for a moment, always searching for a better way to phrase his words. “Maybe nothing more poetic?” he added. “You know sometimes it is best not to know too much, don’t you agree?”

I knew Arnost enough to know that “don’t you agree” was rhetorical.

We didn’t order, but the large man in the white smock brought two more beers, marked them on a white slip of paper on the table, and walked away. After a while we toasted toward the relief of Hrabal on the wall.

“Okay,” I said. “Here’s what I think: He wrote that if God really loved him, he’d just drop dead over a beer at the Golden Tiger.” We laughed hard and Arnost raised his eyebrows, nodded slowly, and finished his drink. “Finish up,” he said. “I have to lecture in thirty minutes or so.”

It was a time of extremes. I drank in every morsel of life from the minds of men who cracked open history and edited the outcome. It was a time to speak of the tragic haunting of dead relatives and the mystical power of words. One man finds romance in the crumbling memories of internment, and the other loses faith in God. Sometimes soldiers, whether fighter pilots or writers, dilute death and inhumanity with beer, while others drink to celebrate what’s left.

Sometimes they spend a weekend watching Chaplin films and talk about home and how it was before before the Nazis and the Communists cared about Prague, the trashing of books, the elimination of a race, the fatal tumblings of souls.

Later that night I left the university alone and went to the hospital on my way back to my apartment. I stopped and stared, counting floors to five, and wondered what Hrabal would have written about next. He was in his early eighties when he died; there was still plenty of time. I left, but turned back briefly and gazed at the façade for a few minutes.

I didn’t see a single pigeon anywhere.

About a week later, I returned to Terezine with Arnost and a friend of his, Academy Award winning filmmaker, Milos Foreman. On that particular day in 2000 Arnost needed to talk to Milos who wanted to make a movie based upon Arnost’s book The Unloved. He made beautiful movies like One Flew Over the Cockoo’s Nest, Man on the Moon, Heartburn, and others including my favorite, Amadeus.

At some point on that cool afternoon between conversations about the horrific ghetto museum of Terezin and the prison for anti-Nazi protesters, the Small Fortress, I ended up having a conversation with Milos about adaptation. He discovered that subject matter to be the focus of my lectures at the university. It seems the theme of my entire time in Prague that year was Adaptation.

“So we agree then,” he said to me. He was much younger than Arnost with the same controlling conversational style.

“Yes,” I said, “Of course. It is always frustrating when people say how much more they like the book, or do any form of comparison at all. They are completely separate art forms.”

“Exactly! I can’t film all of a book!”

We talked further about our common concern on the subject of movies based upon a novel or play, and we reiterated the inability of people to see movies and books they are based upon as separate. Yet we also agreed on the difficult task of expecting anything else of the average person at a movie on a Saturday afternoon.

Eventually, of course, the talk turned to his work.

“Yes,” I said. “I’ve taught both “Cockoo’s Nest” as well as Amadeus, and I did read Kesey’s book as well as Shaffer’s play, which I first saw when I was in college.”

“Well?”

“Both times you nailed it. From Kesey’s novel you kept the major themes which worked and consolidated what needed to be. In Amadeus you made music the central theme of the movie instead of the ridiculous “mystery” between Mozart and Salieri. I still enjoy watching both films and teaching them. Oh, and Amadeus has the BEST cut in movies, when Mozart is in bed and Salieri finally hands him the completed “Requiem,” and Mozart says, “Okay, from the beginning,” and we hear an entire orchestra for the first time as his wife’s horse and carriage come into view. Love that scene.”

Milos indicated it was hard to miss with such material and brilliant film editors, but I appealed. He was a great director.

Then he mentioned Ragtime.

When I was young my father bought me E.L Doctorow’s book. I loved it and read if several times. I loved how it swept across decades and included some major historical figures such as Houdini. But I never could picture it as a movie; even if one could save the major themes, it simply is too complicated to pull off as a traditional narrative with the proper conflicts clarified.

Then I saw the movie and I didn’t like it all that much. I even watched it again after I learned a few things about adaptation at Penn State, and it still, for me, didn’t work. I even left behind my memory of the book and focused solely on the new art form, trying the best I could to not include the literature in my analysis.

“What about Ragtime,” Milos said.

I thought about saying, That was really some casting they did for “Cockoo’s Nest,” wasn’t it? But I could tell he was enjoying our conversation. I looked at his Czech copy of The Unloved in his hands. It was bookmarked and folded and noted in dozens of places. He clearly learned the book as if it were his own, like his films each became his own, not Kesey’s or Shaffer’s and definitely not Doctorow’s.

“It seemed too complicated to capture,” I said.

“Yes,” he agreed, reflectively. “It never did convey the themes well. Or at least the way I wanted to.”

“It seemed more of a vehicle for Cagney seeing as it was his last film.” I was feeling ballsy now in the conversation.

“You’re probably right. He got more attention than the film. Will you discuss these films tomorrow in your class?”

“No. I’m moving on to Hrabal’s Closely Watched Trains.” He smiled. Milos was a fan and friend of Hrabal’s. As Arnost said, the Prague art community is not very big.

I told him I was going to talk about how adaptation of one art form into another involves both deciding what essential elements must make the transition and which ones very specifically needed to be left behind.

Arnost returned, always sharp, always ready for what’s next. I stared at this man’s eyes and thought about how much he went through. The Nazi’s disrupted his life, caged him for three years as a workhorse, forced him to build a railroad from Terezin to the mainline on the way to Auschwitz, killed his family, and still he escaped. And still he went on to not only live his life, but live it fully as a writer. He knew what to take with him after the war and he knew what he need not address ever again. His entire life was about what to leave in and what to leave out.

It is not easy, adapting, saving the best of what exists, our strengths, and leaving behind the weaknesses, the parts we wish we could do over given the chance.