I’d like to peel away the layers I’ve adopted over the course of decades. I’d love to let go of tethers, let the twirling plates drop to the ground and shatter. When we were in Spain, I discovered how wealthy I felt when I had just what I carried across the Pyrenees. And when we were at Spirit Lake, I learned quickly how much more at peace I am and remain when the distractions are three thousand miles east. And when I was sitting around a camp fire in eastern Senegal with no water, no news, no electricity, not anything different over the course of a hundred years, the conversation never ran dry, the laughter always pure and honest, and the stars—oh, wow, the stars—I lay on my back at night and drifted in the saturated sky for hours.

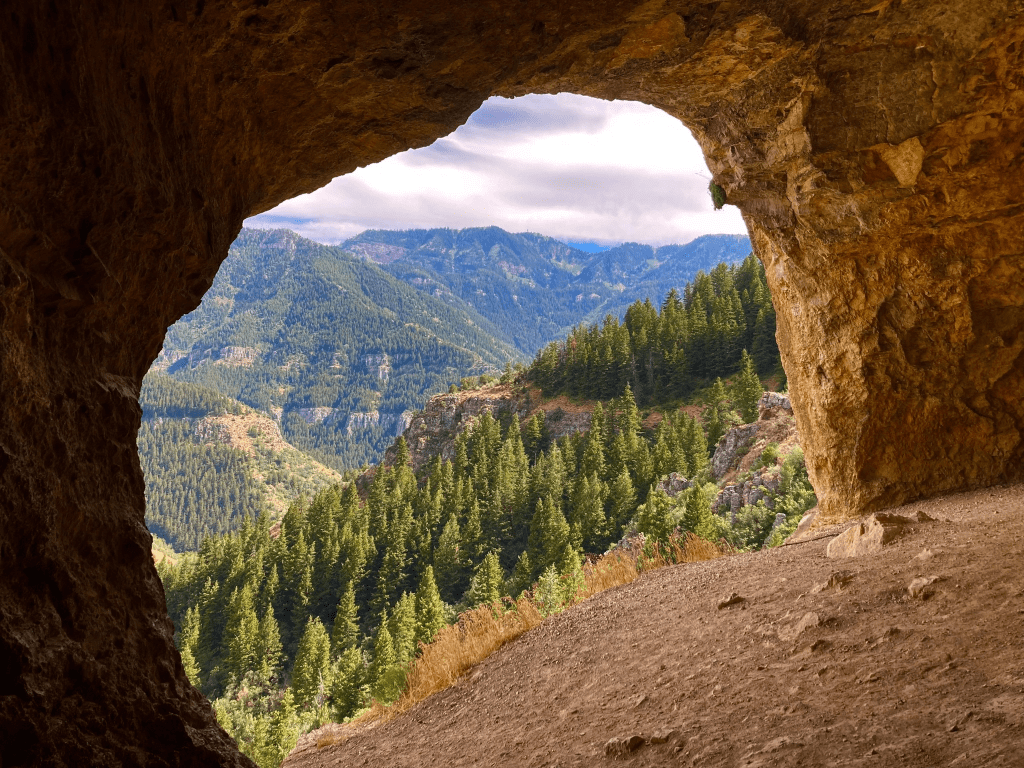

I find myself in less need now of most things than I ever have before. I’m going to spend more time in nature, in Oregon, in the Catskills, in France. In Ireland and Alaska. I want to listen to the earth as she was meant to be heard, not through the filters of inventions and progress.

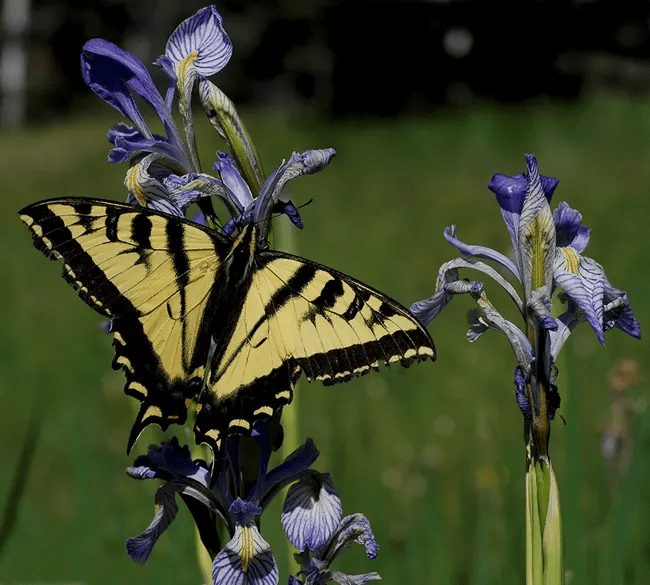

It’s raining tonight, finally warm enough to not snow or sleet, but cool enough to know it’s winter. The drops on the skylight above my head soothe me like they do when they do so on a tent when I am inside resting and the world is raining. There is something magical about how being in the wilderness can keep my attention, and Muir is right when he wrote that the clearest way to the universe is through a forest wilderness. Still, it’s taken me some time to understand why: it is absolute presence. I am wholly in the moment, the rain, the cool temperature and the sound of the rain and often geese in the distance looking for a field or pond just at the bottom of the hill.

Nature knows nothing except now. I sit at this desk and everything in this room has ties to back when. Mementos of travels, piles of unfinished work, guitars and a few bins of items from autumn or Christmas I’ve not yet put in the attic. It is the same anywhere in the house, with songlines running right through to some other where or when. But the minute I step outside and gaze deep into the woods or walk the hill to the river and look out across the bay, nothing exists but now in that nature, and I am completely aware of the air, the sounds, the conditions on the water and the cloud cover. And Zhuangzi’s note that “the sound of water says what I think” is present and true. There is nothing else like the sound of water in nature, rain, rivers, small creeks which have carved around and through rocks since before humans created the notion of earlier and later, created the beasts known as before and after, created the disabling “remember when we” and “why don’t we.” Cities and towns are linked always to others and plans and histories. Even at events people sit and talk about other places, different times.

But in nature, in the mountains out west or the porch out front, I can sit and listen to the rain and slow my pulse to something primitive, something organic, and I can dial up Emerson who suggested we adopt “the pace of nature; her secret is patience.”

No, I’ve had no mushrooms tonight, no Rioja or Malibu. Maybe a little. But no, my awareness tonight is from the rain, and I know Dar Williams’ comments “The beauty of the rain is how it falls” brings me closer to why I’ve managed to suspend the passing of time, for now, anyway.