Memory is as fluid as anything in our lives. What happened and what “seemed to happen,” as writer Tim O’Brien points out, can often be confused. When looking back we might have a habit to recall what seemed to happen, reality having been washed and hung out to dry over the course of decades. Sometimes though we can recall nearly ever nuance of a time in our lives for its significance, its uniqueness, or its romance. I have a pretty sharp memory when it comes to many events. A friend of mine and I were talking not long ago about how we can both remember nearly every detail, everything, about a period in our lives so long ago you’d think it was from another life. Many of us have times like those which, for whatever psychological reason, we can summon up to the point of remembering the clothes we wore on a particular day.

My basic memory for most things is pretty solid. I remember all my phone numbers and license plates, and, worse, the phone numbers and license plates of friends of mine. The old joke about song lyrics holds true with me, but so do the times spent with extended family. One of my only memories of my paternal grandfather was him weeding a lot he owned next door to his house on Long Island. He died when I was five, so I was no older than that, probably still four. But I picture that day, those moments, perfectly.

Some years ago when Meanwhile in Leningrad came out, someone asked how I can remember the conversations I had with survivors of the Siege of Leningrad, who at the time I knew them were in their eighties, and I wrote the book several years after our conversations. I said, well, first of all, they’re never going to find or read the book, so there’s that. But more accurately, when a woman sitting on a bench holding my hand tells me about dragging her dead husband and son across the city to leave in a mass grave, and she sat with me clinging to their photograph sixty years later, I will not forget any of it. Much of the writing in that book falls in that category. Did the conversation happen verbatim? Doubtful, but the gist of it is pretty damn accurate. There’s an old journalism method that when you write the piece and include quotes from someone, call them up and read what you wrote to them and ask, “That’s pretty much what happened, right?” Nearly all the time they’ll say yes. Can you remember the words, exactly the words, you spoke an hour ago? Exactly. If that’s not possible as in this case, I rely on memory and notes.

Memory is reliable or not depending upon just how present we are during the event. That time so long ago when we said we could remember everything: We were both very much present at the time, we lived the example of what would later be called “mindfulness.” Of course we remember. Likewise there are times I so shut out of my memory it’s like they never happened at all.

Still, some events are so close to my soul I would need the team from Matrix to come extract them.

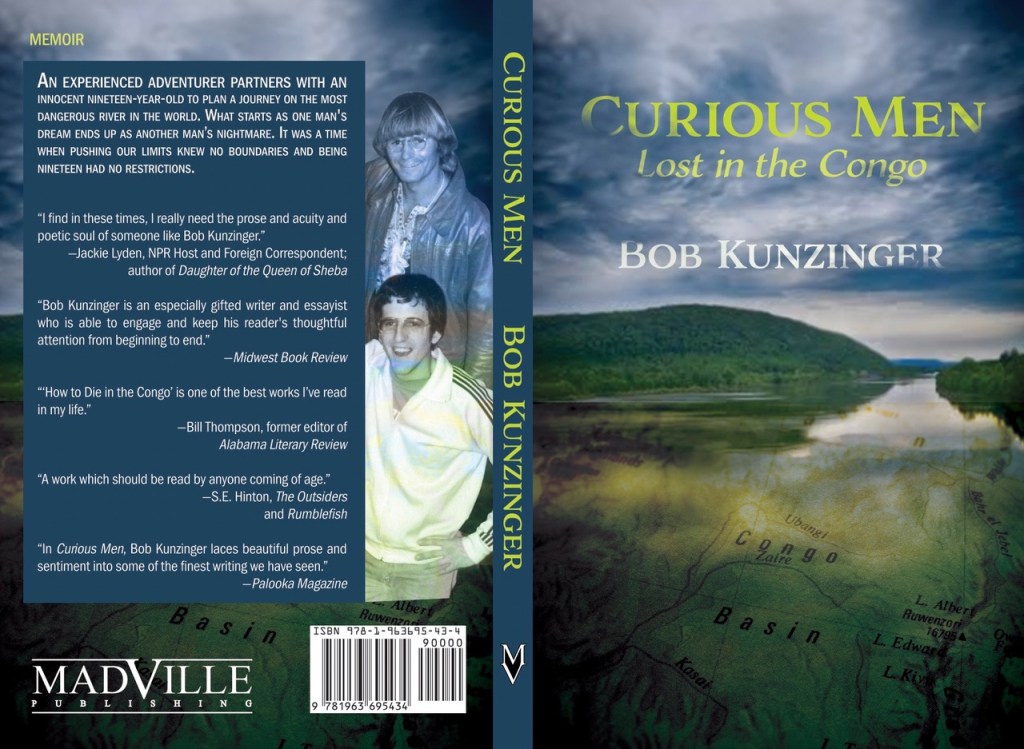

Like what happened in 1980 and 81, when I was a freshman and sophomore in college, the subject of my forthcoming book, Curious Men, from Madville Press. Of that time then, I remember everything. I watched, studied, and listened so intently that this memoir could be considered a documentary for how clear the details remain to me four and a half decades later.

I like that “memoir” includes the Spanish word “oir,” to hear, because much of memory stems from what we hear, and as a nonfiction writer I am bound by listening to the world around me, sometimes to the one sitting in front of me, and those sounds of vowels and consonants and the musicality of language I know will never escape my recollection.

My friend, colleague, and former officemate, Tom Williams, once introduced me at a reading as a non-fiction writer by saying, “Here’s some shit that happened to Bob and the best he can remember of it.” That’s pretty spot on. Despite a degree in journalism, I never had what it took to do the job in the traditional sense like so many I graduated with, some of whom have won prestigious awards for their work. I was definitively not up to that task. But I could handle the feature work, the “Let me tell you what just happened to me” work, just fine. In college, my friend Deb used to help me with news stories and I’d help her with features. We knew our strengths. I had a column in the college paper for which I ventured out into the community and did something, and then I wrote about it. I went horseback riding in Machias, New York, flew planes in Wellsville, kayaked the lake in Allegheny State Park, and sat on the ground behind campus at Merton’s Heart. Those events I could remember. I knew how to be present. Most of those activities were out of my wheelhouse at the time, so recalling what happened was easier. I was paying closer attention, sometimes just so I wouldn’t die.

Memoir is like that. If we can’t remember it we’re certainly not going to write about it.

But not this time, not this book. Summation: As a college freshman uninterested in the normal activities of my floormates–that is, drinking and drinking–I felt lost and disconnected from everyone. Then a family friend returned from the Peace Corps and asked me to help him plan a trip, solo, on the Congo River. So I did.

Long story short, it didn’t work out and his trip became mine. The first half of the book takes place in western New York. The second half in the Congo.

Still, that’s not what the books about.

Most of it takes place now, in every classroom across America where nineteen-year-olds sit and try and find something worth doing, something that reaches deep inside them and wakes them up. I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty-six years and one thing hasn’t changed: they’re scared out of their minds. They’re alone in a new place far from home living in a room this size of their car with a total stranger, and every adult within earshot constantly wants to know their plans for their major, their careers, their lives. It is often unbearable.

I was exactly like that back then. Until a friend walked into my life and said, “I have an idea. I need your help.”

We were so young.

So that’s what this memoir is about: About that time back then. What we did and how and why we did it, yes, but mostly about being nineteen and far from home looking for a reason to exist at all.

This is how I remember it.

Coming this winter: