I have chosen to be present.

The river is icy tonight; not frozen at all but frothy on the whitecaps, foam along the sand. The sky was clear last night adding to the bone-chilling air, and the stars and planets filled the horizon. Tonight, however, it is cloudy, low dark clouds heavy with snow and eventual ice as a storm approaches, one like we have never seen before, so we are told. This is, this is not, a metaphor. Yesterday morning the sky and the bay seemed one, both calm, a mirror, still, complete peace, and the blue of the sky and the blue of the bay were only interrupted by a white cloud stretching across both. Tonight the water is rough, choppy, the spray stings the skin, and standing outside too long is dangerous, deadly.

Nature does what she wants, as well.

A soft sound came out of the woods earlier, rustling but heavier. I thought it was a deer at first, or the fox who visited the other night, or perhaps the racoon family which lives in one of the trees behind the shed and spends much of their time under the shed. But it wasn’t. A cat came out of the brush and sat on the icy stones and stared at me. I tried to coax her to the porch, but she simply meowed and moved away. I followed briefly but that only chased her further, so I retreated inside remembering my own cat who died some years ago and who, when he wanted to come inside, would leap from the front rail to high up the screen door to look through the thin windows at the top. When he saw me get up to go to the door in the back, he’d leap back to the porch, run around the house and slide inside. The cat earlier looked a little like him, a grey tabby, but this one had too much white. For a little while I was fine in the encompassing world of the cat in the driveway, and I felt such peace to be so present.

There will be Ice tomorrow. Again. So before I went inside, I stood for a moment in the chilly air and listened to the silence stretching far across the river and the bay, far inland as well, through the woods and into the night. No marches here tonight, no protests, no threats. No starving children waiting for medical care in Gaza or homeless in Ukraine, freezing. No unpredictable folly, no disparaging comments, no ridicule or mockery or distasteful gestures. No needless deaths or poor excuses, no narcissistic nonsense, no impatient though warranted commentary from allies. We live in a world now where no one is reading opinions unless they already agree. Heather Cox Richardson is preaching to the choir. So is Fox news. ICE shoots at will. The president acts without restraint. Congress doesn’t act at all. The news stopped covering the Epstein Files, Venezuela, the bombing of boats in the Gulf, the skyrocketing cost of healthcare, the impending shutdown, the redistricting debacle, the purchase of the Supreme Court justices. I can’t breathe.

I’m moving on, maybe longer than planned. Across the pond and then the river and far out beyond the Norris Bridge up river I heard geese approaching, their honks growing in volume and number, until they scattered about and landed in the fields and the ponds and the shoreline, hundreds of them, more, and they quieted down so that only a few calls could be heard and after ten minutes or so it was quiet again, the water choppy forcing them to find the sand, and other than that, just the silence of a heavy sky about to snow.

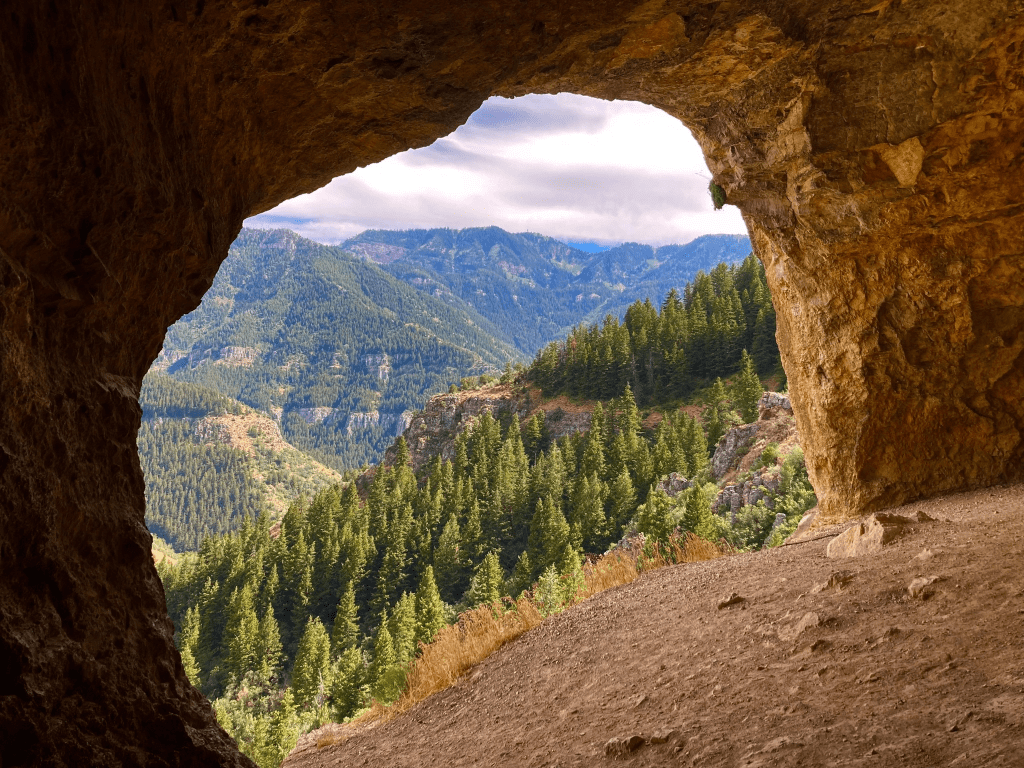

I have spent mornings here for three decades and no mornings are the same, the geese or ducks or herons and me, the rising sun, the setting sun, the hole in the sky of the moon, and we, it, are never the same. It is the same in the Uinta’s, the Catskills, the Blue Ridge, the same in the fields of Neunen, the trails throughout the Commonwealth, Nogales, St Petersburg, the Mala Strana, the Sahel, the Lofoton’s, the same silence, same presence, the same sense I never want to leave. The peace that comes when you know you have no need for yet more change.

I am fine here, at the water, or there, in the hills, or down along the clear endless coastline with water moving in and then away, completely oblivious to the mayhem, the seeming end of a republic. I am fine in a state of unknowing, cousin to the ostrich, brother to the deceased, though still here just the same.

And it occurs to me tonight as the streets of Minneapolis are aglow with the burning fires of defiance, and the world is ridden with anxiety because of one demented mind, that I have always been this way, along the Great South Bay, the Allegany, the canyons in Arizona, and the central New England hills where kettles of hawks kept me company on clear summer nights, not so much avoidance as control, predictability and allowance. I could so easily disappear to the east of Tangier, to the west of Coos Bay, to the North of Minnesota where if we focus on what we should focus on, is exactly where the light gets in.

So I have chosen, as well, in the spirit of Shen Yu, to only experience what I choose to focus on.

“If I disappear, look for me in moving waters”

–Robert Redford