Note: I wrote this piece nearly exactly as it reads below not long after the invasion of Iraq. Originally, I sent it to Dan Latimer, who at the time was editor of The Southern Humanities Review. He rejected it. About a year later at a reading in Atlanta, I read this, and Dan came up after and said, “I love that piece! Is it published? I want to use it in the SHR.” It was a few years later after he published several other works of mine I told him of his initial rejection of “Sliced Bread.” A year after the initial publication, Dan wrote to congratulate me; “Sliced Bread” was noted in Best American Essays, edited that year by Adam Gopnik. Since then it has been anthologized several times and even taught at a university in Taiwan. It remains one of my favorite pieces. I watched Oppenheimer again the other night and thought of this. Thank you for reading/sharing.

Sliced Bread

Tennessee Williams ate cornbread, as does Bill Clinton. Hemingway ate anything toasted. Vladimir Putin likes pumpernickel, named, according to spurious account, by Napoleon during war with Russia when he demanded a loaf of bread for his horse, Nicole, and shouted, “Pain pour Nicole.” Jacques Chirac chooses French from the Mediterranean region while Vincente Fox finds southern Mexico’s flatbread best with paella and beans.

Reagan liked sourdough. Nixon, a connoisseur of fine food, enjoyed sliced wheat bread and lightly buttered popovers, as does Margaret Thatcher. Thom Jefferson like Sally Lunn, of course. Mao didn’t eat bread. Stalin soaked black bread in beer and Lenin liked rolls. Alexander the Great relied upon some form of flatbread, while Ivan the Terrible ate black bread. Seafarers fared fine on hard biscuits inedible without sopping up soup or grog, and the staff of life literally saved the lives of millions during the nine-hundred-day siege of Leningrad during World War II, when bakers mixed breadcrumbs with sawdust to trick the stomach into feeling full. While mothers waited for food, while children starved to death, the Nazis pounded the city from the south with endless bombings. Hitler ate rye.

Which made me wonder about George W. Bush, so I Googled “Bush + Bread” and came up with “Damper Bread—a favorite in the Australian Bush.” Campers eat this horrific outback specialty in the wild. They bake damper in the hot ashes of the campfires in the outback dirt. It tastes disgusting but the sustenance is often necessary. Still, this tells me nothing, and I don’t think Bush bakes bread in the ashes of his Crawford ranch.

But just below that entry is “damper bomb.” This small exploding device can be manufactured at home for just dollars and will smoke out or kill anyone in the house. The damper bomb how-to page notes, “This is not a smart idea.” I should think not.

This same search, however, exposes “Smart Bombs” as a brilliant result of precision technology. They’re designed with a sensor system that uses a battery and onboard controls. Instead of just being dropped from an airplane as dumb bombs are, smart bombs are dropped then guided to their computed targets. They essentially become heavy gliders. Dumb bombs, however, fall helplessly.

So I searched “dumb bombs” further and found “Dum Bread.” This is a round loaf that indentured servants brought to the Caribbean from India after slavery. The dough was sweetened with coconut and placed in a covered skillet and fried on coals. More coals were placed on the lid. Later, wheat flour was added to the dough and the result was called Smart Bread. It can sit heavy in the stomach, however.

Equally difficult to digest is Daisy Bread. It is the most popular treat at the Lighthouse Bakery in England. It is dense, but pulls apart into pieces that resemble daisies. For an extra few pounds hungry daisy-eaters can add soup. The cook admits the weighty combination. “It’ll warm you up, though,” he says.

So will the infamous Daisy Cutter Bomb. This cutter is essentially a dumb bomb weighing in at fifteen thousand pounds with more than six tons of explosives. Someone thought this was a smart idea. These bombs were common in Afghanistan but became most popular in Vietnam, where soldiers were hungry for landing-zone clearings. One of these twenty-seven-thousand-dollar-apiece bombs could clear an area three-quarters of a mile wide, including all buildings and rock formations. One of the problems with the Daisy is that the pilot must fly low, right over the target, so the wind won’t carry the bomb off course. They cost a lot of dough for such dangerous operations.

The fact that I searched for Bush and Bread and came up with bombs at first seems ironic. Not so much. Since I’ve already stumbled upon heavy bread and bombs, I look for the two in one shot and come up with MOAB, the Mother of All Bombs. This weighs in at twenty-one thousand pounds with nine tons of explosives. It’s the largest non-nuclear bomb in the world and is considered a Smart Bomb because of its gliding ability through GPS. It sprays a highly flammable liquid mist and then explodes about six feet above the ground for maximum impact. This monster is the size of a Jeep Cherokee. In 2002, Donald Rumsfeld said as far as weapons were concerned, the MOAB was the greatest invention since…well, how trite.

Truckers often stop at the Moab Bakery and Brewery in Moab, Utah. There they serve a popular bread bowl filled with whatever soup customers desire, along with some fine microbrew, for a few dollars. Moab is appropriately named; it means “beautiful land,” and Utah sure is beautiful. Of course, Moab also rests above one of the world’s largest uranium deposits.

The name has a biblical reference as well; it means “of the father.” Turns out that after Lot escaped from Sodom, his two daughters got him drunk and had sex with him. They both gave birth to sons and named the oldest Moab, whose primary diet consisted of salted bread. The territory in which they settled became known as Moab and one of the leading Moabites was Ruth, the great-grandmother of Kind David, whose lineage cuts directly to Christ. The first breadline, perhaps.

To go back:

Ancient Mesopotamians nearly nine thousand years ago chewed wheat grain. Eventually, the pulverized from, heated, tasted better, especially when they accidentally added yeast. It didn’t take them long to figure out that pulling off some of the old dough to use as starter for new dough would speed the process, and sourdough was born. In about 1000 BC, they grew a new strain of wheat which allowed them to make white bread. They ate thirty different varieties and washed it down with their most popular brew—beer. This all spread to Greece, which carried it to Italy, where grain and bread became the primary sustenance and monetary unit. Soldiers didn’t mind so much if they missed out on the meat, but don’t dare short them the bread. And the Roman welfare state was based on the distribution of grain to the citizens. Eventually, the government even baked the bread for them.

In 186 BC, the bakers formed a guild, making baking a separate profession. They enjoyed special privileges and theirs was the only trade carried out by freemen, not slaves. The members of the guild were not allowed to mix with regular people and were prohibited from attending events at the coliseum for fear they would be “tainted,” contaminated with the vices of ordinary folk. Romans loved rich breads with eggs and butter, but their favorite was white bread, made with special wheat grain, and to eat white bread indicated one was special. However, bakers considered it somewhat stupid, recognizing what the rest of the world would discover later—dark bread simply tastes better. Bakers believed it was bad taste to eat white bread.

Still, throughout most of history, white bread was an elite product since the grain was more expensive, and darker breads were distributed to the poor. Eventually, that switched and darker breads became renowned for their taste, making them more expensive. Through the dark ages, bread helped humanity rise above the plagues. Bread prevented suicide; bread filled young stomachs when nothing else worked; it was used for trade, as a status symbol, as an aphrodisiac. During the French Revolution, the Bread Riots nearly collapsed the government, giving rise to the myth of Marie Antoinette’s insensitivity: her supposed declaration that the poor, for whom bread was too good, should eat cake instead. Beer and bread were the two staples of life throughout the Middle East for centuries. Mothers used to send their children to school with both.

But even the Egyptians, who greatly improved bread-making recognized that the origin of the process and the best-tasting bread came from Mesopotamia, where the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers form the Fertile Plain.

Modern-day Baghdad.

The irony is so thick you can slice it.

The wheel was invented here, and the great mathematicians of ancient Greece recognized the Fertile Plain area as the source of their inspiration. Ancient Mesopotamia gave the world the first metal-working, architecture, city-building, urban planning, legal system, medical writings, cobblestone streets, and even beer. All of these six millennia and billions of loaves of bread ago.

The first bread with a name was called Lotus Bread. Flatbread with little or no yeast, it was used mostly to sop up oil and gravy in the meal so as not to allow anything to go to waste. Pita is a modern form of this. Roti in India; hleb in Russia; pan in Spain; brot in Germany; ogi in Basque; pao in Portugal; ekmek in Turkey; non e barbari in Iran; and in Iraq, khubz—the correct name for pita, taken from the Hebrew and Arabic. It’s the most widely eaten bread in the world. The Body of Christ is a middle-Eastern recipe. Michelangelo ate pita, as did the first popes. It is available at the Lotus Bakery in England, which also makes bread and rolls from the finest spelt flour, grown in the Middle East for nine thousand years. Today, farmers grow nearly a thousand varieties of wheat grain but still only one strain of spelt. And according to the Lotus Bakery it is easier to digest and tastes better than wheat.

The Lotus Bombing Principle is more difficult to swallow.

This declares that an independent government has a right to defend itself with whatever method is not prohibited. Here’s the problem: the World Court, in determining that states have the right to use nuclear weapons to defend themselves, ironically determined that states have the right to choose a course of action that could conceivably lead to the extinction of humanity. But not allowing the state that right would not allow them to carry out an action that is not prohibited under the law of the World Court; the “lotus” principle. Confused?

Simple: The world governments with money and know-how set out to find and extinguish nuclear weapons of mass destruction from the arsenals of governments considered “high risk,” Bush’s “Axis of Evil” members. And how do they find them?

Yeast.

As it turns out, yeast functions like a scout, or a canary in a coal mine. If yeast cells are exposed to dangerous chemicals they change color and die. Scientists genetically modified yeast so that when something happens to its cells they change color. These yeast cells are placed on the backs of cockroaches—a species which can apparently survive a nuclear war. The roaches are then sent into places where someone might hide dangerous chemicals or weapons. These yeast cells can stay alive for several days, and that is long enough to keep an eye on the little indestructible suckers to see where they’ve been and if, when they come out, the yeast cells have turned color.

So war and bread apparently need each other. However, I still need to know the president’s favorite bread. In need of aspirin as well, I wander to the drug store, where the clerk watches Oprah, and who’s her guest but the Commander-in-Chief himself. I watch the way one watches a NASCAR race: waiting for, just expecting, an accident, but she keeps the questions relatively simple. One of them is his favorite food—I can’t believe it.

“Oh,” the president says, “I love peanut butter and jelly on white bread.” I pegged the president as a white bread loafer from the start, with maybe an occasional drift toward tortillas. But any WWII Navy personnel could predict he’d go for the PBJ because the PBJ-1 was the US Navy’s designation for the famous B-25 Mitchell Twin-engine bomber. It had a mounted upper turret and retractable radar unit along with the ability to carry a single torpedo fitted outside the bomb bay. One of the Mitchell’s finest hours was the Doolittle Raid in which Jimmy Doolittle led a group of PBJs off the carrier Hornet in a bombing raid of Tokyo. Many years later, President Reagan and Vice President George H.W. Bush awarded Doolittle the Presidential Medal of Freedom for “dropping the bombs that led to the end of the war.” During Doolittle’s tours overseas, he was allotted four ounces of bread per day.

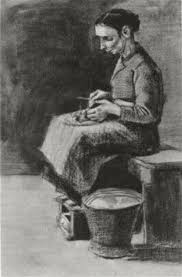

According to Saint Don Bosco, a nineteenth-century Silesian priest, our only salvation from the bombs that will rain down is the “bread of life.” Saint Don would have eaten mostly flatbreads from Northern Italy. The year Bosco died, Van Gogh wrote that he ate only “bread and whatever beer I can borrow from the innkeeper from the night café to keep myself from suicide.” Van Gogh liked sourdough. Snoopy eats wheat toast. My son likes hard-crusted Italian. My father likes white bread; he voted for Bush.

In America last year we spent about seven billion dollars on bread. The workers who built the pyramids were paid in bread. The great fire of London started in a bakery. Of the more than six billion people on the planet, nearly five and a half billion of them rely upon bread as their primary nourishment. Meanwhile, that same number has at one time or another in the last five years been in some sort of volatile conflict.

Julia Child once wondered, “How can a nation be great if its bread tastes like Kleenex?” Henry Miller said you might travel fifty thousand miles in American without once tasting good bread. Gandhi said there are “people in the world so hungry that God cannot appear to them except in the form of bread.” Francis Bacon said acorns must have been good enough to eat until bread was found. And he wasn’t far off; the first bread probably tasted nutty.

Bread is a slang word for money. Bread is the staple of life, both nutritionally and spiritually. Thomas Merton wrote, “Stale bread is much closer to crumbs and I am humbled by that.” Plato believed an ideal state “where men would go to their grave old was one where people ate locally grown whole grain wheat.” Socrates, on the other hand, believed whole grain bread to be pig food. Christ probably ate Parthian bread, and the loaves that fed thousands were a similar variety. “Companion,” literally translated, means one with whom we “break bread.” Bread is the staple of civilization; it keeps the seams from unraveling.

When a movie fails in the United States, it is considered a “bomb.” When it succeeds in London it is considered a “bomb.” In both cases the word comes from the Latin, bombus, which means “a booming sound.” Bread, on the other hand, is derived from the Hebrew, which is known in some lexicon circles as the “mother of all tongues.” To brew, the root of the word “bread,” is to concoct. No wonder warm beer and bread have been linked since biblical times. Certainly those downing loaves of Parthian must have been getting bombed along the way. Dwight Eisenhower said, “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies in the final sense a theft from those who hunger and are not fed.” Eisenhower liked Irish soda bread.

Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project, upon watching the first atomic explosion in 1945 quoted a Sanskrit verse from the Bhagavad-Gita. He whispered, “I am death, destroyer of worlds.”

Oppenheimer loved white bread, lightly toasted, with butter.