The Shed was twenty-feet deep by eight feet wide, with two windows, two lofts, double doors, and sturdy enough to withstand everything except Hurricane Isabel.

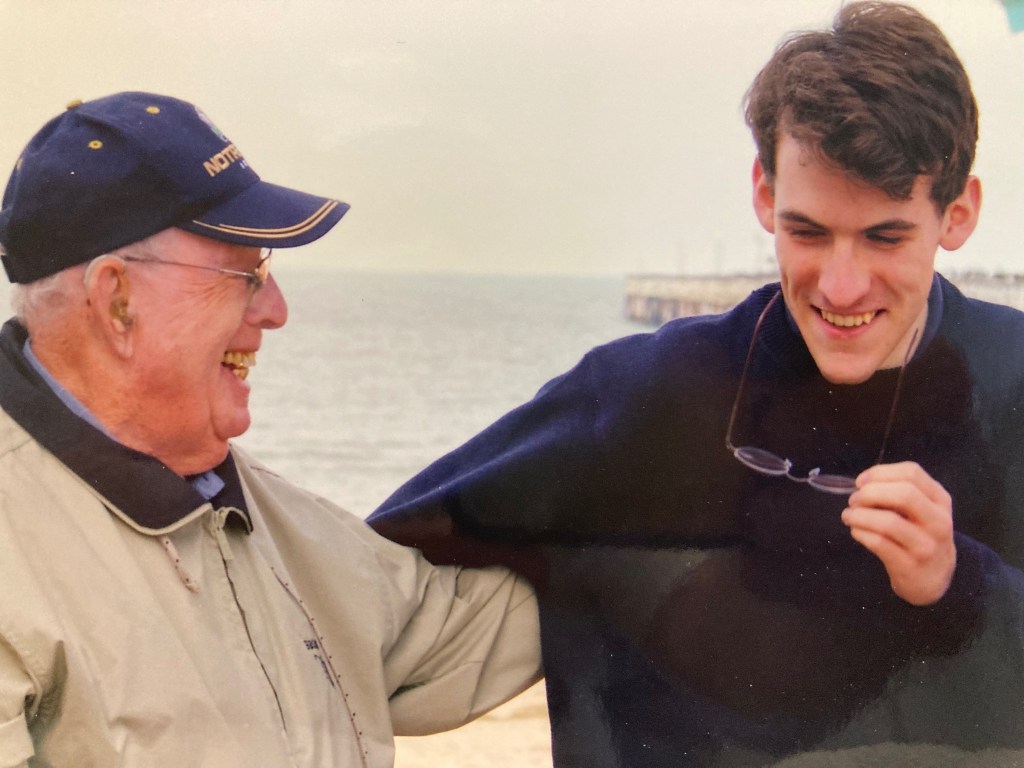

Of course, I bought the shed to hold supplies when I was building the house. Before I started, when I had first cleared the small portion of the property for the home, I had this shed delivered figuring I might need to sleep in during bad weather while up here for three of four days in a row seventy-five miles from the place in Virginia Beach. Michael and I went together to the shed place in Virginia Beach. Some guy paid for it but never picked it up so I bought it brand new for a song and the father and son team I bought it from delivered it seventy-five miles, across the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, across the still-narrow Coleman Bridge, the Piankatank bridge, and down my winding driveway through the woods—for twenty-five dollars. I also bought them lunch.

It didn’t take long, as it tends not to take, to have stories to tell from the shed.

Back in ’99 we had fifteen inches of rain in two days and the water ran from the river side of the property down to the woods beyond the shed. I had the shed leveled off the ground by about eight inches on blocks, so the water rushed toward the door but instead dug crevices under the shed. The shed, miraculously was dry, but impossible to get to.

Isabel didn’t do a thing to the shed, but she knocked down thirty oak trees here at Aerie, and one of them lingered for weeks right above the shed. I knew it had to come down but this was a job I couldn’t pull off myself. Scavengers wanted more than fifteen thousand dollars to clear the fallen trees, so I said I’d do them myself, which I did, but I was afraid to cut the half-fallen tree in fear it would crush the shed. Instead, another storm just a few months later cracked the trunk and it crushed the back half of the shed for me. I remembering thinking, “Hell, I could have done that.”

So in the lemonade tradition, I made the back half into a greenhouse with plastic sheets for the roof, but it didn’t really work, and over time the mold and mildew and various snakes and wood rot got the best of The Shed. It took about twenty-seven years.

One time early when Michael was about five, we played hide and seek as we often did, and I ran in the shed while he was still too far away to follow me right in, but he could see me. I then climbed out the back window and settled behind the back wall. I heard him come in the shed and was quiet for a minute then said, to no one in particular, “Holy Cow, How did he do that? Daddy?”

I remember how we laughed.

We built things with wood and made signs and birdhouses. None of them were well done but they were all perfect. Occasionally we’d take a break and play “Voices.” That is, we’d recreate “Wind in the Willows,” and I was the voice of most of the characters—Badger, Toad, Moley, even the stoats.

And we kept the sporting equipment in there and played frisbee, football, golf, and ring toss, which we still do nearly thirty years later when outside barbequing.

The bikes he kept in the shed got bigger, and the toys were relegated to the loft while more accessible spaces were reserved for tools, chemistry sets, then inflatable kayaks and eventually equipment to hold his art supplies and frames.

When he was little, he would tie me up in a chair with a lasso his uncle sent him from Texas, and he kept lizards and frogs in tanks until he couldn’t feed them anymore and would let them go behind the shed, in the woods.

He kept buckets of fake snakes and lizards in there when he was young, and when the roof collapsed and water raged in, it carried the rubber reptiles out the door and under the shed. The next day I spent an hour reaching under the shed and pulling out the toys, until one reach pulled out amongst the fake snakes a real one with red and yellow and black, and I forgot the rhyme about poisonous snakes so I just threw everything as far as I could.

There were other days like that.

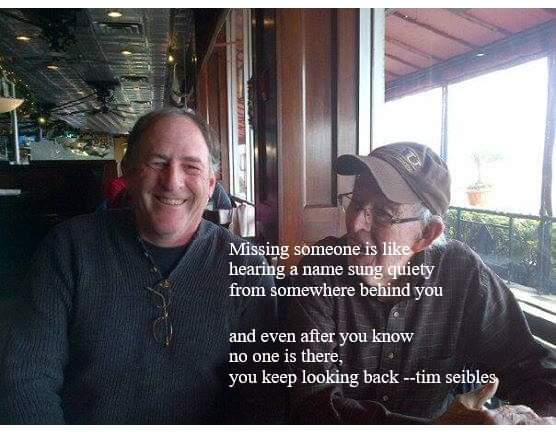

But there’s a hole out there tonight. And Michael is in Ireland, far from the fallen shed. It had to come down. I had to do it now or we’d be still out in the still standing shed telling stories.

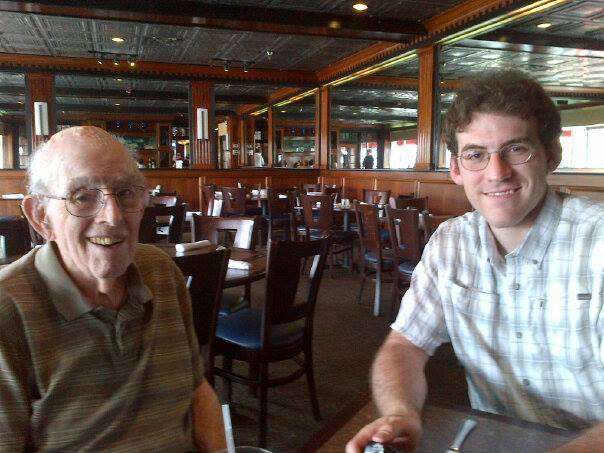

I destroyed the last of it a few hours ago, and I rested on the nearby patio remembering the times we shared for his entire life, and the talks we had—so many talks we had safe in the shed, just the two of us, about growing up and traveling and things that frustrated us, and things we were scared of. Out in the country like this along the bay when a father and son go into the shed, usually it is for some form of punishment, “a whooping” as they say. Well I never had a reason to punish Michael; but we did have plans to make, so out to the shed we’d go, and he’d make notes on wood with a nail, and we’d plan adventures like training across Siberia or walking across Spain.

We kept tools in that shed, and mowers, bikes, grills, and more. And memories filled the spaces between everything else. We let a lot of memories occupy that space.

Funny though. I sat out there today when I had finished knocking it down and thought about the next week or so during which I will haul away the remnants, clean up the ground, lay down some field stones and mulch in front of a much smaller, new shed, put a few chairs and a small table there, and I tried to imagine the new way it will be, and it made me a bit sad, of course, but excited for a new place to talk. But lingering a bit in the hot afternoon air was the sound of ten-year-old Michael playing his harmonica and the distant hint of his unchanged voice asking if I want to play hide and seek.

There are some things that shed kept safe for us I’ll never be able to destroy.

Now:

Next: