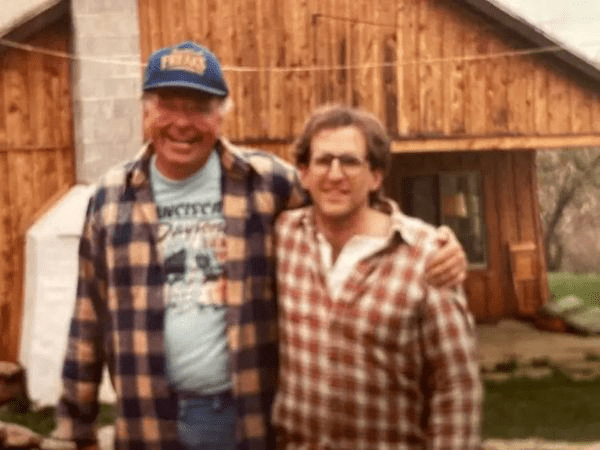

I was nineteen, Dave Szymanski eighteen, and Fr. Dan Riley thirty-six years old. I met Dave because I simply met him; I’m not sure where or when but we were both J majors and worked for both the campus newspaper and radio station, WSBU, 88.3 FM. I met Fr. Dan when just weeks into my freshman year I caught the Russian flu and ended up in the infirmary, and he’d come by every evening and sit bedside and we’d talk; instant friends.

Early that fall we started a radio show. Dave and Fr. Dan were hosts and I was the producer and engineer. “Inscape” aired every Saturday morning for an hour, with open discussion about spiritual matters, a deeper conversation with a new guest each week, and a musical artist for interludes. The guests included Fr. Mathias Doyle, college president, Charles Osgood, CBS newsman and St. Bonaventure favorite, author Fr. Roy Gasnick, an expert on St. Francis of Assisi, and Fr. Irenaeus Herscher, campus librarian and archivist, close friend of the late Thomas Merton, and namesake of what would become Mt. Irenaeus (yes, named after the good priest, not the saint himself).

One fall day in 1979, Fr. Dan and I met early for breakfast at Mary’s in Allegany, and we walked in the chilly air for an hour and talked about hopes and fears, about friendships and families, and we continued that conversation consistently until July 23rd, 2024—the day before he died. We talked, we texted, we emailed, snail mailed, visited each other, and shared writing—he sent copies of my book Penance to a dozen friends of his, I sent copies of his book Franciscan Lectio to a dozen friends of mine. I have piles of letters from Dan; over 300 spanning four decades. We consulted each other. When Dave died, his widow asked me to call Fr. Dan. When he answered the phone before I could speak, he said, “Bobby! I’m glad you called! I don’t like you anymore and I don’t want to be friends with you!” and despite his eighty-one-year-old frailty, he laughed the laugh he is known for by tens of thousands of students across five decades. He added, “Brother Kevin is sitting right here, and I want to tell him something. Kevin, it’s Bob. We don’t like him anymore,” and they both laughed. Then I said, “I’m not calling you for a good reason” and he slipped right into Franciscan-priest mode, his voice going deeper and more serious, and I gave him the news of Dave’s death. For some time we remembered those innocent days in the Fall of ’79.

Jimmy Carter was president, the Iranian hostage crisis (kids, watch Argo to understand) was underway, and Inscape—a Merton term for escaping within—was on the air, and one of our early guests was Fr. Irenaeus, the featured music was from James Taylor. The theme music for the radio show which lasted for two years was by Dan’s fellow Rochester native, Chuck Mangione’s “Hills Where the Lord Hides.” Reference: This was forty-five years ago this fall. Dan, Dave, and I with a dozen others were about to go on a retreat to a place called “Vic’s Cabin,” and it would be the first of many retreats in various mountain areas over the next four years while he looked for a permanent location for spiritual retreats for students.

On that show, the three of them talked about retreats as Fr. Irenaeus spoke softly and with such kindness about how his friend Fr. Louis—Thomas Merton—thought retreats were essential to the human soul, and the same of St. Francis. He said he personally believed a true retreat, however, was about community as well, where people can be alone, yet with others, in silent prayer but in living gospel. Fr. Dan smiled wide, his brown mustache stretching to his ears, him nodding, repeating, “Yes, exactly.” After the show we walked Fr. Irenaeus back to the friary. A few days later he was hospitalized for several months and died not long after that. Fr. Dan and I walked back to the dorm we both lived in and sat in his apartment on the fourth floor and talked about the retreat scheduled for early November.

I graduated. I moved about: Arizona, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, all the while exchanging letters with Fr. Dan, and in early May of 1989 I drove to what had become Mt. Irenaeus near West Clarksville, New York, to spend the weekend talking to him, helping out around the two-hundred or so acres. Construction on the Holy Peace Chapel had begun, but only the frame was standing at that time, and Dan and I worked on a small stone edging of a path to run through the woods to the chapel entrance. It was in the upper sixties and we laughed and talked for hours, noting the beautiful spring day and the budding trees. On Saturday morning I woke to his bellowing laughter and walked into the small hallway of the original house of peace for the mountain. He walked me to the door and pointed—it had snowed six inches overnight.

Everyone left over the course of the next few hours, but I stayed by his insistence to enjoy the weekend and write—I did, and the journal by my side now is called “These Days: The Weekend Alone at Mt. Irenaeus” but I’ve never published it. Still, I noted many of our conversations from the previous day, including Dan’s fear the Mount would become too big to handle; too popular to remain personal.

No one was there and they had not stocked the pantry yet except for cereal, so I spent the next two days eating Captain Crunch and walking through the pines in snow, surrounded by absolute peace, taking advantage of the chance to inscape.

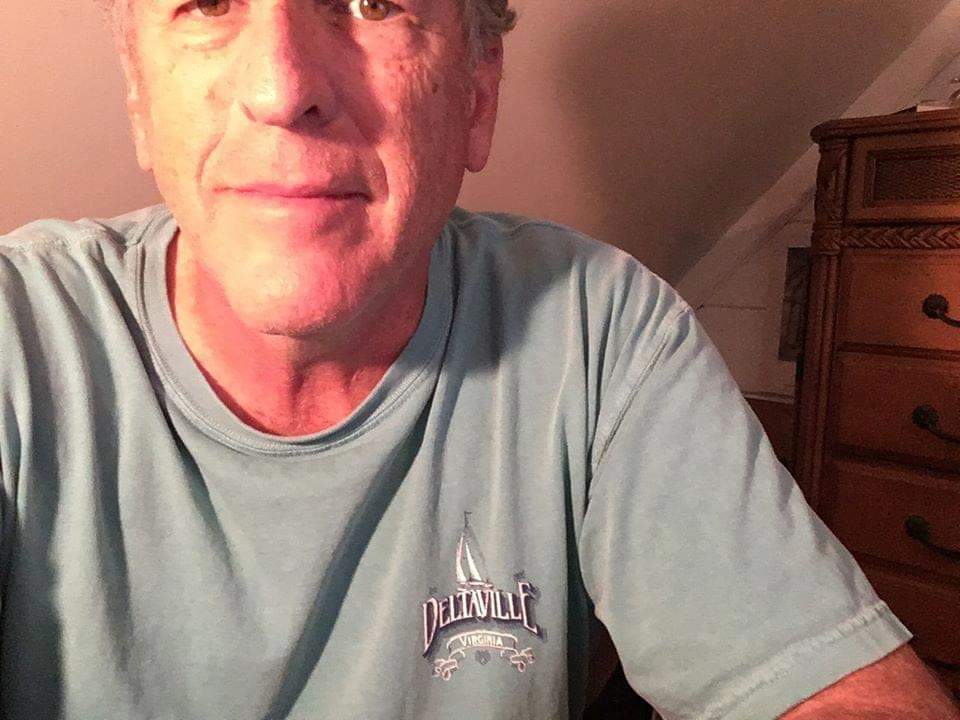

But everyone who knew him, which was everyone who went to St. Bonaventure University since the mid-seventies, has stories about time with Fr. Dan Riley. The first time I met his family, they kept calling him Billy (Fr. Dan’s birth name is William) and I joked “I’m going to start calling you Fr Billy from now on,” and he quipped—with his dark eyes peering across his glasses at me to demonstrate his seriousness, “No. You’re not.”

When my son had a solo show of his abstract art at the Quick Center for the Arts on campus, Fr. Dan let Michael know his old friend, Tony Bannon, former director of the George Eastman Museum of Photography and the oldest photography museum in the world, thought Michael’s work was one of the best and most unique catalogs of photography he had ever seen. Fr. Dan seemed so proud, and so energetic about all people and the moments we shared. Not long ago before his passing he recalled how he enjoyed telling Michael what Tony had said.

But listen, everyone who knew him has stories. It is what raises Fr. Dan up from the status of “friend” to the realm of mentor, truly, without equal, the seeming recurrence of St. Francis of Assisi himself in virtually every way, for Fr. Dan’s influence on students, community, and faculty of the university helped him almost single-handedly, like Francis, rebuild the church in the hearts and souls of us all.

Late one night a couple of years ago he and I sat in the House of Peace drinking Baileys and he nodded toward a poster on the cabinet entering the kitchen. It says, “Ending World Hunger Starts Here: Please Don’t Waste Food.” “I remember when you had those posters made,” he told me, “and when you started the World Hunger Committee on campus your sophomore year.”

“Yes,” I said. “I told one of the Wintermantels—I think Dan—what I wanted it to look like and we made thirty of them. I’m glad one survived to be here at the mountain.”

“Whenever I look at that or think of the outreach programs for the hungry, I think of you,” he told me, and I realized how far I had strayed from those days. It was then I understood why Dan and the mountain remained a place that I needed to return to from time to time to understand who I am at the core.

***

My mother was very ill and on July 23rd, 2024, I texted Fr. Dan. He called me immediately and we talked awhile, laughing of course, and he said he would pray for her, naturally. I told him I had a reading up North the end of September and planned to come by the mountain to visit if he would be there.

He said, “Yes, Bobby, I’ll be here. I’ll always be here for you. I can’t talk right now, he said, but I’ll call you tomorrow night.” When I hung up, I received this text: “I certainly will be remembering your mother in prayer. Probably Kevin is coming by and I’ll ask him to have the community hold her in prayers as well. Your memory of her certainly will bring you comfort even though eventually when someone you love dies there is great pain. Peace, and all good my dearest friend. Dan.”

The very next night I walked from the hospital to my car to find my phone lit up with messages. I remembered then that Fr. Dan had said he’d call me that night, but the messages weren’t from him. They were about him. My dear friend had died that day, July 24th, 2024.

Yes, memories bring comfort despite the great pain. I wonder often why we lose our innocence to such a damaging degree that we need to go back to find it. At retreats back then–particularly that first one at Vic’s Cabin, we talked about how to carry that peace with us instead of looking for it out in the world. One night not long later I was depressed for what could have been a dozen reasons, and I wandered to Dan’s room where three of four guys were hanging out talking, and I joined them. Eventually, they left, and I told Fr. Dan how much better I felt just sitting and talking, and I wondered why. Dan smiled and said. “Bobby. You brought the peace with you this time.”

Amen.

I imagine now Dan is off in the hills where the Lord hides.