A friend and I were texting today about age, about our inability sometimes to remember how old we are; especially when we both have been fortunate enough to have parents live into their nineties. It is difficult to feel like a senior citizen when you’re out to lunch with your mom laughing and eating pizza.

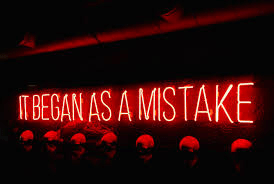

But we certainly have aged, and it’s not going to get easier. Toward the end of our exchange I related how I know I’ve made countless mistakes through the years, particularly the last several, but I’m still here and as long as I can rise tomorrow, I can make amends for those mistakes, or, more likely, make even bigger mistakes.

It’s called being alive.

Here’s one:

When I first went to Russia in the early nineties, an orthodox nun asked me to kneel next to her and she prayed for me for ten minutes at the Shrine of St Xenia, one of the patron saints of St. Petersburg. Then she gave me a piece of bread from the top of the sarcophagus and asked if I liked it. I wanted to say yes, I enjoyed her blessed bread, but my weak language skills kicked in and I told her, “I love you and I lust for your black God.”

It feels odd to make mistakes in a foreign language. Oh, there’s more:

I wanted to ask a cab driver where I could find a bathroom but ended up saying I like to drink dark beer from a toilet.

I told someone I thought was a waitress who turned out to be a prostitute what I thought was yes I could use a few minutes to think but turned out to be yes I’d absolutely love oral sex. I turned to a friend with me at the bar and said wow, the service here is phenomenal.

I wanted to tell a room full of students to listen, but instead I told them to get their suitcases.

I pulled out a chair for a lady and told her to heel.

I asked for five Danishes and walked out with fifty.

A priest friend of mine stationed in the city wanted to tell a waitress he would like some mayonnaise but ended up saying I love to masturbate.

Some friends went to buy coffee and asked me how to ask for sugar. I told them. It turns out the word for sugar is “Suga” but the word for bitch is “Suka.” They returned exclaiming Don’t ask for sugar in your coffee in Russia, Dude; they’re assholes about it.

I could go on but more or less by screwing up I learned to fit in, pick up the nuances of accent and syllables, which brought down prices at the flea market, brought out their best Georgian wine, and opened gates to closed graveyards and monasteries.

My mistakes are some of my best memories. Even the ones which broke my heart, left me penniless, crushed my ambition. Sometimes we don’t know they are mistakes at the time—our lives are filled with those incidents. Acutely optimistic people will tell me those aren’t mistakes, they’re lessons. No, they’re mistakes. I can honestly look back at certain moments in my life—no matter how sure I was of my decision at the time—and say, definitively, I screwed up.

But we move on and hope we are forgiven; we keep going and learn to forgive ourselves.

At the back of one church, in the rubble of what was and would eventually again be St Catherine’s Catholic Church, a woman stood looking for a priest I knew. She seemed confused and we talked a bit—slowly of course. Her mother had been the secretary of the church before the revolution seventy-five years earlier. She needed to see the father. In my weak Russian I determined the woman told me she had a huge cross to bear because of the horrors of communism for all those decades and wanted the priest to take the sins away from her, but when Fr. Frank appeared with sharper language skills than mine, his translation was somewhat more significant. Sitting outside was the original cross for the church dating back hundreds of years, which she had brought with her, and which her mother had taken when the Bolsheviks took control after World War One and had buried in the yard at their dacha where it remained for seventy-five years. She thought it was time to return it.

My bad.

Back at home and much more recently I showed my students how to present a paper using the guidelines from the Modern Language Association. I gave them copies, I presented another example on the outline, I asked them to open their books to the appropriate example in the text, and still forty percent of them did it completely wrong. Is that a mistake? Is that boredom? Distraction? Idiocy? I like to think they are overwhelmed and go home kicking themselves for doing something wrong that was so easy to get right, but I’m probably mistaken. A few years ago I would have returned to a class like that and lectured them about how their priorities are screwed up; I would have told them that if they can’t get the easy stuff done, they’ll never handle the challenges as they attempt to move up the collegiate ladder. I would have used the appropriate sarcasm with a touch of professorial belittling attitude.

But last January I was driving through the Pennsylvania countryside on my way to western New York on a Sunday morning when I heard a guest on a talk show quote St. Bernard of Clairvaux who said we need to learn to make excuses for other people.

We need to learn to make excuses for other people.

If we can see other people’s reasons for their failures, their errors, their need over and over again for help despite being helped so many times before; if we can consider the myriad possibilities that they might need help other than the knee-jerk reasons we label them with, the world changes. For us, for them. It gets lighter, somewhat more manageable.

Sometimes students come in later and we see laziness, disrespect, disregard.

We need to learn to make excuses for other people.

I once had a student who came in late because her husband is stationed in Iraq and she got to talk to him that afternoon. Another one told me after the fact that she left early because her father had died that afternoon. The one who couldn’t get the presentation correct no matter how hard he tried has never been the same since returning from war. No one would know that to watch him stumble through a relatively easy assignment; but a little background information illuminates so much.

The one who stared at me the entire class without blinking an eye, then left, only to later email me to apologize for not concentrating; she had just learned her cousin was shown on television in Baghdad, dead, and left swinging from a bridge. I taught in a different environment in the military rich resort city of Virginia Beach. I wish I had learned to make excuses for other people earlier in my career.

St. Francis de Sales said, “Never confuse your mistakes with your value.”

I’m trying. Mostly, I hope beyond hope that others, particularly those I’m closest to, make excuses for me.

I suppose, though, in all honestly, that sometimes we really can be lazy assed howl-at-the-moon stupid people. I do it all the time. Make no mistake about that.