This article, the most shared of any I’ve written, originally appeared in the Washington Post, May 29, 2016.

From This Green Hill

by Bob Kunzinger

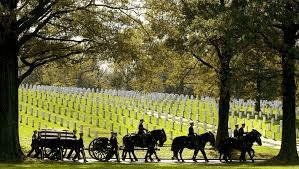

I was at Arlington National Cemetery and stood near a small wall on a tranquil hillside, and I could see Washington, D.C., the Washington Monument and other memorials to our Founding Fathers.

The unobstructed view looks out upon our nation’s capital, where for almost 250 years some of these souls have challenged the balance of power. A few of our former leaders lie just feet from this unassuming spot: an eternal flame for John F. Kennedy, a small cross for his brother Robert and, for their older brother, Joseph, one of the hauntingly familiar headstones. Across these green fields in all directions stand thousands upon thousands of marble markers, all carefully carved with the names of veterans and spouses, their birth and death dates, battalion or division and rank and conflict, a cross or a star, variations of both. A flag.

From this protected promontory I could see century-old oaks. Magnolias and dogwoods shrouded headstones like commanders keeping their soldiers safe. The Tomb of the Unknowns, mausoleums, small, singular sarcophagi and miniature monolith monuments stood scattered across acres of fields of fallen men and women who once stood as strong as those very stones that mark their last battle.

From this green hill I could see wildlife. I watched brave birds feed at an arm’s length away and then scatter to the safety of a nearby branch. Starlings perched upon headstones, and striking red cardinals gazed from the low branches of a tall maple. It was theirs, once, as were all the battlefields and all the cemeteries from Winchendon, Massachusetts, to the Texas Coastal Bend, before these battles took their toll, and men — boys — were buried in this wilderness.

From this tear-soaked soil I could see Vietnam, its rivers and forests where death kept too close to birth, whose beauty and wilderness taught men to pray and made brothers of them all. I could see the village battles between unknown enemies and blameless boys who should have been home riding bikes and reading books. I could see the more than fifty-thousand Americans never to become authors or professors, scientists or librarians, gathered beneath this field where their legacy is our common charge.

Beyond the Potomac, I could see Korea, the Philippines and New Guinea. The voices of spouses still crying for a husband to come home, women, standing alone too young, holding the small hands of children starting their fatherless flights toward tomorrow. I could see the medals and markers, veterans hugging veterans above a brother’s eternal assignment, saying, “It should have been me.” “He gave it all.” “He saved my life.” “He was too young.”

From this hallowed ground I could see Normandy. I could see the parachutes falling under the cover of night. I could see rows upon rows of men who marched side by side through shallow, blood-filled, mine-laden water toward the only hope left. I could see the hillside and the secured toehold. I could see the American flags on Omaha Beach and Utah Beach. I could see the graves of those forever beneath foreign soil and the ships returning with thousands of heroes. I could hear taps, the prayers of priests, the commanders’ thank-yous, the nation’s solace.

From this sacred spot I could see into France, the sacrificial fields, the trenches that saved the lives of our great-grandfathers. I could see the muddy, barren no-man’s land where brave men crossed only to lie here, now, beneath crosses too many to mention.

From this vantage I could see the heirs of Lexington and Concord. I could see Saratoga and Yorktown. I could see the battle for freedom, the commitment to integrity, the promise to defend. I could see the fight for the greater good. From this spot on a green hill I could see a small group of men standing like stone walls against England and claiming with absolute clarity and without compromise that we will be free. We will stay free. We will not fail.

From that green hill, from that perspective on such honorable sacrifice, I could see what bought our freedom. I could count the crosses, the sum of which cannot be measured, whose cost cannot be calculated.