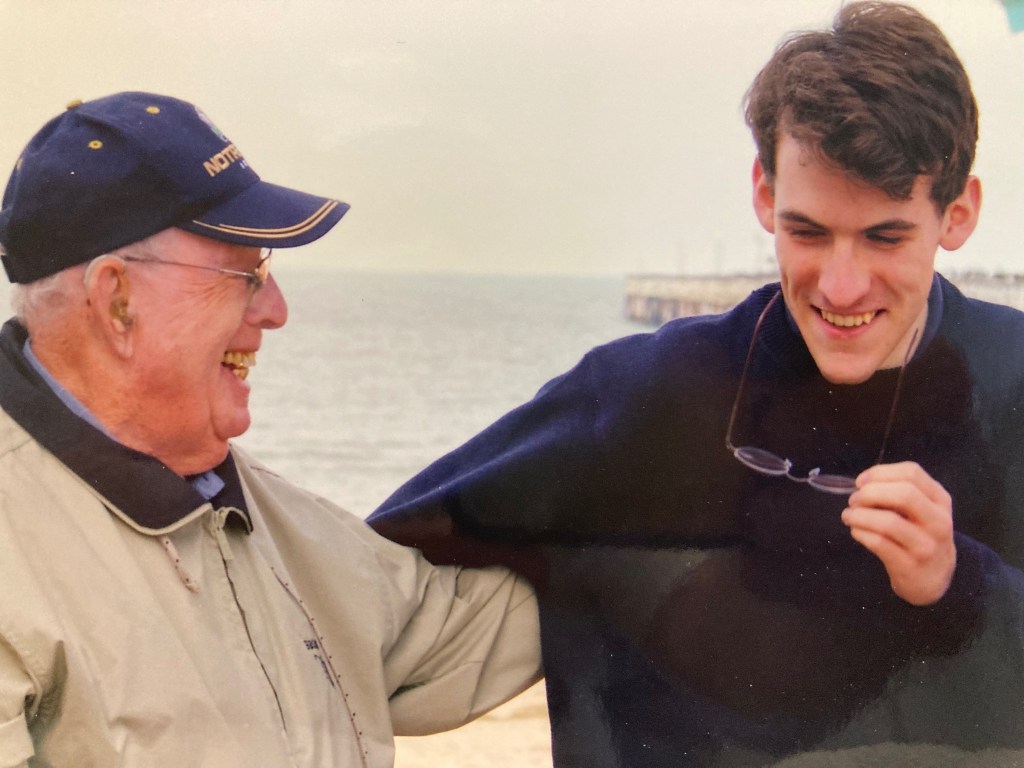

Dad had a toll-free number, so for most of my life when I traveled I could call him at his desk for free. I’d be about to enter Mexico through Nogales, Arizona, and I’d find a pay phone and tell him I was going back down for more blankets and some Kahlua. He’d laugh and offer his “Well be careful” in his deep voice, and for some reason I always knew, despite his desk job on Wall Street and in Virginia, his troubled feet which kept him out of the service, I knew he wished he were out there with me. I once called from Massachusetts to tell him I wouldn’t be able to call for a few days because I was going whale watching off of Maine with a friend, and he was truly excited. I wasn’t going whale watching, though; I was flying to Virginia along with his entire extended family to surprise him for his sixtieth birthday. When he came in his house and he saw me among the crowd, he actually looked disappointed that I wasn’t out on some vessel in the Maritime Provinces. That was Dad. Quiet. Proud. And kinder than just about any person I’ve ever known.

Funny how I just assume all dads should be like him. And maybe to each of us in some way our own father is the model. I’m guilty of not emulating him earlier. As much as my memory tells me he worked a lot–leaving the house for the Long Island Railroad at the crack of dawn and returning barely in time for dinner five days a week, and after dinner, coffee, the newspaper, he’d watch television, burned out from another long day on Wall Street, somehow he fit us all in without complaint–ever–as if nothing else mattered but being around family. What an example he set without ever offering one single word of advice. That’s how to Dad.

When my son and I traveled across Siberia by train for a book project which became The Iron Scar: A Father and Son in Siberia, the original writings from the trip, many of which were published while he was still with us, were written in the form of letters from me to him about Michael and me headed through Russia. In those pages I wondered if he was such a good father because he lost his own Dad when I was just five, and perhaps we are never completely fathers or sons when we’re between two living generations. Eventually, the book became a narrative instead of a series of letters, but he is always present in the pages. At the time of the trip and subsequent year or so while working on the book, he was slipping away just as my son was coming of age to head out on his own, so comparison was instinctive, and I could say with complete objectivity that my son turned out to have the same personality–kind, caring, without judgement–as my father. It was somewhere near Irkutsk I understood that my father lives on in the way my siblings and I as well as our kids live our lives.

For a man who worked all the time, though, he was always there: He brought me on my first flight, first class, from Norfolk to LA when I was fifteen. He taught me to drive. He would come by my office after he retired and see if I had time to go to lunch. Mom and us kids were his life; and when family visited our house for holidays or just a Sunday afternoon barbeque, he was in his glory. Nothing mattered to him more than us; that was clear though he never, ever said so. That’s how to do it.

Random thoughts:

I saw him cry twice. The evening of the day my sister told him she was diagnosed with aggressive Stage Four Ovarian Cancer, and the evening of the day she told him she beat it.

The last thing I wrote which he could read, according to my mother, was “Instructions for Walking with an Old Man at the Mall.”

His face always lit up every time my then-toddler son and I would “accidentally” run into him at the stores.

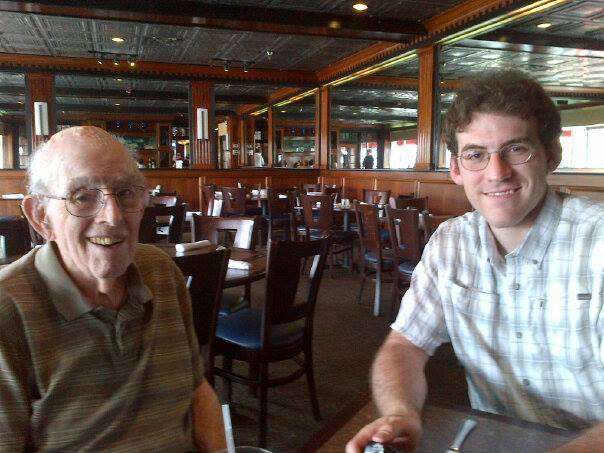

Every Tuesday night we had Scotch. I hated Scotch but I loved Tuesday nights.

Every Super Bowl we sat in his living room and watched while eating wings and shrimp. It is the only time I ever saw him eat chicken wings, on Super Bowl Sunday.

He loved watching baseball and golf. To this day, when I hear golf or baseball on television, I think of Dad and miss him again.

He would go downstairs first on Christmas morning to plug in the tree lights. With a smirk at 5: 30 am he’d quip “I thought I told you no one up before nine!” He would wait until Christmas night when our relatives had left and we were all sitting around to give us each one last gift, books he picked out with each of us in mind.

I never knew my grandfathers. But my son and my father were as much friends as they were anything else. They were together a lot for Michael’s entire life until he was twenty-two, and we’d play golf regularly, especially when my brother came to town, and every month or more the three of us or the four of us would go to lunch at the beach, and sometimes we’d just go to his house while Mom was still working and sit and talk, or go out on the porch and watch the birds out on the river, and when Michael was still a toddler he would take his hand and walk him to the edge of the water to look for wildlife. I could have posted hundreds of photos of the two of them, and perhaps just as many as the two of us since Michael always had a camera with him.

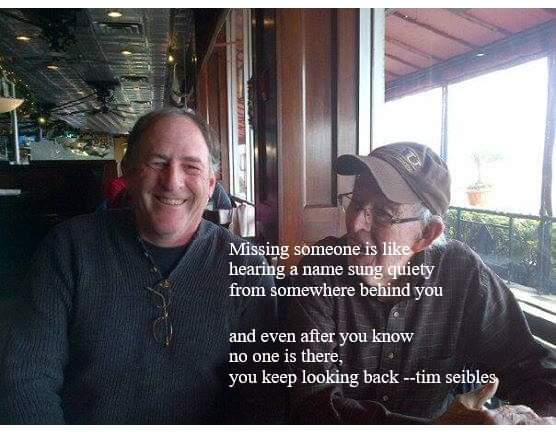

But I see no need. I can hear his voice as clearly as I can hear these keyboard keys, see his face as if he was sitting right here. I’m not in denial about Dad’s passing at ninety-years old, ten years ago this October, but it isn’t unusual still for me to have a conversation with him, or almost pick up the phone to call him about going to lunch. I suppose it will always be that way, and I’m okay with that.

Some days are tough, of course, just as they must have been for him after his dad passed when Dad was just forty-years old. But he never showed it that I recall; he just continued to Dad us, and I am lucky–fortunate, blessed, grateful, honored, humbled–he was my father.

From The Iron Scar: A Father and Son in Siberia:

I guess you have to be a parent to understand what kind of child you were. You need a basis of comparison that goes beyond the parent-child relationships of cousins or friends. It must be later, years later, when you understand what he would have wanted you to ask, what he wished you had shown interest in, how close–or not close–you were. Turns out we were so much closer than I knew, and I could have asked anything, but I never did.

Happy Birthday Dad. I love you.