One:

Two:

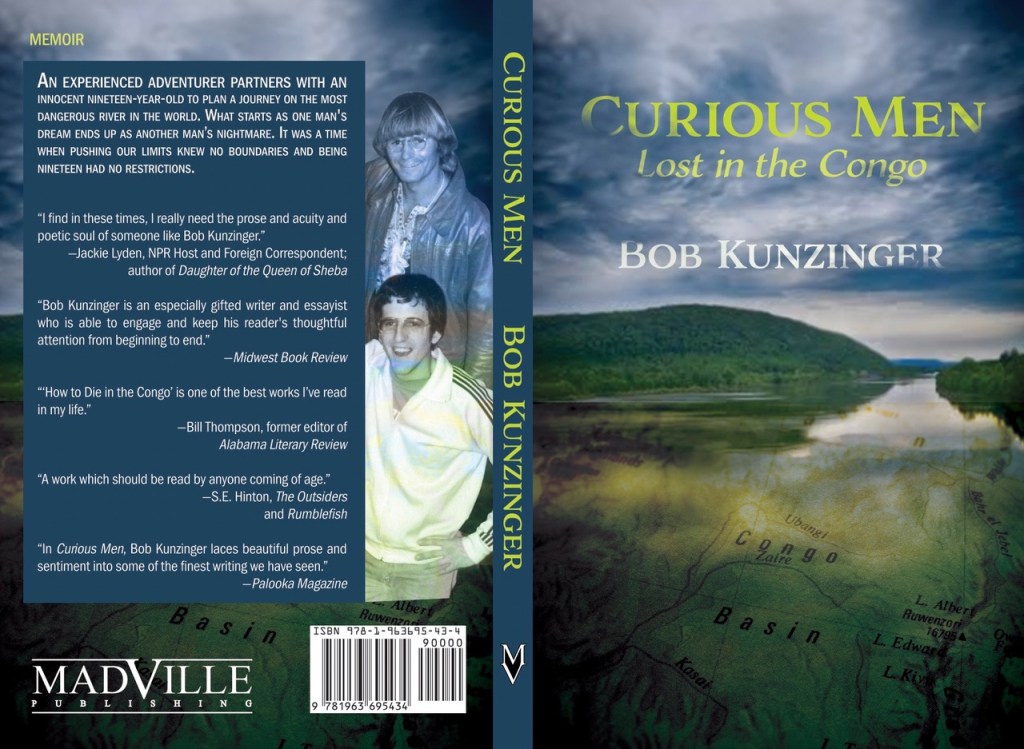

CLICK ON THE BOOK COVER BELOW TO ORDER:

Memory is as fluid as anything in our lives. What happened and what “seemed to happen,” as writer Tim O’Brien points out, can often be confused. When looking back we might have a habit to recall what seemed to happen, reality having been washed and hung out to dry over the course of decades. Sometimes though we can recall nearly ever nuance of a time in our lives for its significance, its uniqueness, or its romance. I have a pretty sharp memory when it comes to many events. A friend of mine and I were talking not long ago about how we can both remember nearly every detail, everything, about a period in our lives so long ago you’d think it was from another life. Many of us have times like those which, for whatever psychological reason, we can summon up to the point of remembering the clothes we wore on a particular day.

My basic memory for most things is pretty solid. I remember all my phone numbers and license plates, and, worse, the phone numbers and license plates of friends of mine. The old joke about song lyrics holds true with me, but so do the times spent with extended family. One of my only memories of my paternal grandfather was him weeding a lot he owned next door to his house on Long Island. He died when I was five, so I was no older than that, probably still four. But I picture that day, those moments, perfectly.

Some years ago when Meanwhile in Leningrad came out, someone asked how I can remember the conversations I had with survivors of the Siege of Leningrad, who at the time I knew them were in their eighties, and I wrote the book several years after our conversations. I said, well, first of all, they’re never going to find or read the book, so there’s that. But more accurately, when a woman sitting on a bench holding my hand tells me about dragging her dead husband and son across the city to leave in a mass grave, and she sat with me clinging to their photograph sixty years later, I will not forget any of it. Much of the writing in that book falls in that category. Did the conversation happen verbatim? Doubtful, but the gist of it is pretty damn accurate. There’s an old journalism method that when you write the piece and include quotes from someone, call them up and read what you wrote to them and ask, “That’s pretty much what happened, right?” Nearly all the time they’ll say yes. Can you remember the words, exactly the words, you spoke an hour ago? Exactly. If that’s not possible as in this case, I rely on memory and notes.

Memory is reliable or not depending upon just how present we are during the event. That time so long ago when we said we could remember everything: We were both very much present at the time, we lived the example of what would later be called “mindfulness.” Of course we remember. Likewise there are times I so shut out of my memory it’s like they never happened at all.

Still, some events are so close to my soul I would need the team from Matrix to come extract them.

Like what happened in 1980 and 81, when I was a freshman and sophomore in college, the subject of my forthcoming book, Curious Men, from Madville Press. Of that time then, I remember everything. I watched, studied, and listened so intently that this memoir could be considered a documentary for how clear the details remain to me four and a half decades later.

I like that “memoir” includes the Spanish word “oir,” to hear, because much of memory stems from what we hear, and as a nonfiction writer I am bound by listening to the world around me, sometimes to the one sitting in front of me, and those sounds of vowels and consonants and the musicality of language I know will never escape my recollection.

My friend, colleague, and former officemate, Tom Williams, once introduced me at a reading as a non-fiction writer by saying, “Here’s some shit that happened to Bob and the best he can remember of it.” That’s pretty spot on. Despite a degree in journalism, I never had what it took to do the job in the traditional sense like so many I graduated with, some of whom have won prestigious awards for their work. I was definitively not up to that task. But I could handle the feature work, the “Let me tell you what just happened to me” work, just fine. In college, my friend Deb used to help me with news stories and I’d help her with features. We knew our strengths. I had a column in the college paper for which I ventured out into the community and did something, and then I wrote about it. I went horseback riding in Machias, New York, flew planes in Wellsville, kayaked the lake in Allegheny State Park, and sat on the ground behind campus at Merton’s Heart. Those events I could remember. I knew how to be present. Most of those activities were out of my wheelhouse at the time, so recalling what happened was easier. I was paying closer attention, sometimes just so I wouldn’t die.

Memoir is like that. If we can’t remember it we’re certainly not going to write about it.

But not this time, not this book. Summation: As a college freshman uninterested in the normal activities of my floormates–that is, drinking and drinking–I felt lost and disconnected from everyone. Then a family friend returned from the Peace Corps and asked me to help him plan a trip, solo, on the Congo River. So I did.

Long story short, it didn’t work out and his trip became mine. The first half of the book takes place in western New York. The second half in the Congo.

Still, that’s not what the books about.

Most of it takes place now, in every classroom across America where nineteen-year-olds sit and try and find something worth doing, something that reaches deep inside them and wakes them up. I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty-six years and one thing hasn’t changed: they’re scared out of their minds. They’re alone in a new place far from home living in a room this size of their car with a total stranger, and every adult within earshot constantly wants to know their plans for their major, their careers, their lives. It is often unbearable.

I was exactly like that back then. Until a friend walked into my life and said, “I have an idea. I need your help.”

We were so young.

So that’s what this memoir is about: About that time back then. What we did and how and why we did it, yes, but mostly about being nineteen and far from home looking for a reason to exist at all.

This is how I remember it.

Coming this winter:

Something is always missing in my writing that I can’t put my finger on. This is normal, and over the years I’ve had conversations about this with everyone from Tim O’Brien to Susan Sontag; that others read your work and say, “That’s exactly right,” all the while you step away from it frustrated that it is still shy of what you meant, what you know it needs, or worse, know it needs something but can’t figure out what. Welcome to the arts. It’s a like/hate relationship. Love rarely shows up except, ironically, during the conception stage when everything makes sense. But later, well, something is always missing.

More than a few times I’ve been asked to read from older works. My last few books I don’t mind reading from because even though I know I could improve what is there, I’m still satisfied with the material. But when I’m reading a piece from one of the two early books about life in Russia I want to apologize as I go, read a few lines, look up and say, “Geez I’m so sorry this is so shitty,” and then continue, sighing after each paragraph. That’s the nature of the beast–actors too don’t watch old films for the same reason. Perhaps we have learned more since then and we approach the early material unfairly from a more experienced perspective. Or perhaps it really did suck and we just hate to realize it is in print somewhere waiting to embarrass us.

But this: I’ve never read something I’ve written and found material I wished I had not included. It is only what’s missing that haunts me, the untold parts, the “I didn’t say that quite right” parts. And then when I recognize what I should have done, when it is clear to me what really is missing, it can be unbearable.

***

It’s hot today, mid-nineties, heat index about 104. I brought my car to the dealer for it’s check-up and I bought new pillows. I spoke to a friend in Ireland, and I talked to someone in Rhinebeck, New York, about a new project. Then I had to make a call to a friend at a newspaper.

You know, some things simply don’t work out no matter how hard you try. I had planned some overseas trips with people that fell through, and two of three book projects have been delayed. So I took the morning to get stuff done and enjoy a little peace. Then I spent an hour on the phone doing an interview with an old friend of mine up north about the book that is coming out this winter, and we talked about those days back in college when much of it takes place. It was nice to look back.

When I thought the questions were done, he recounted my life for me–the books, some of the jobs, most of the years, as a way of matching my work to my experience. And then he asked something that no one had ever asked before and which never really crossed my mind: “Bob,” he said laughing, almost as a rhetorical aside, “is there any aspect of your life you haven’t written about?”

“Bob?”

I was quiet a very long time, and it came into my caffeinated mind like it had been waiting ready to expose itself, and it was quite suddenly and for the first time for me at least, quite obvious.

“Well. Fuck.”

“Yes.”

It took me awhile to understand what just happened in my head, and I apologized, glad he was someone I used to know well enough to not worry about the dead air between us. It didn’t take him long to decide to remain silent, knowing/sensing I needed to get myself together. He quickly changed the subject but I pulled him back. “No, that’s okay. Repeat the question.”

“Just curious if there’s anything significant in your life that might be worthy of a book or even an essay, but you haven’t written about it and, well, why? Why not?” That’s real journalism right there. We had the same mentors but I was never that good. Damn.

It’s always frustrating when something is missing and you can’t put your finger on it. We all know that feeling, like the song that’s on the tip of your tongue, or the meal you prepared and before the guests arrive you step back and feel like there needs to be one more thing, and it turns out to be the most important element. That feeling. Only this time I had the answer; I know what has been missing, what I never wrote about, though it was never a conscious decision. What’s even crazier is I spent part of that phone silence wondering how no one, no one, through the years ever even once asked about it. Ever. Yet it’s absence now seems so crystal clear, like seeing the two shadowy faces that turns out to be a lamp, and once you see the lamp you can’t find the faces anymore.

“So what you’re wondering,” I replied, “is if I ever consciously didn’t write about something that probably deserved to be written about since everything I’ve ever written has been about me, not to sound egocentric or anything.” He laughed and said my work rarely is about me, that I’m just a character in the narrative. This guy is that good at his job. Our mentor Dr. Russell Jandoli would be proud.

“Is there?”

***

Last year I heard a review on NPR of Tim O’Brien’s book American Fantastica, in which the reviewer said, “This is clearly going to be his last book.” I called Tim and we laughed about it and he said he had heard the review and ironically he was already at work on a new book and now he’s thinking of calling it “Posthumously.” We laughed a long time.

“So you’ve got more to say?”

“Yeah, Bob, but it doesn’t mean anyone wants to hear it.”

Well as just another player in the art world I can vouge for the idea that we all just assume no one will ever want to read or listen to or watch our work; that’s not why we create. But, yeah, I still have more to write about as well.

The piece I wrote which was the fastest to go from concept to completion, in ready to be published form, was in 2016 about Arlington National Cemetery. From the time I sat down to write to the moment I sent the version that would eventually be published in the Washington Post spanned just twenty minutes. We call that a lightning strike.

The slowest has been “in progress” for more than forty years, but as of a few days ago it headed to the fast lane and dragged my procrastinating ass with it. Here’s what happened:

When I was a freshmen and sophomore in college, I was deeply involved in the planning and training for a great adventure of a friend of mine who had graduated from the college about four years earlier. While it was not my adventure we planned but his, in just a couple of years it unsuspectingly became mine, and I have tried to write about it ever since. A few pieces have been published by journals such as Matador Review and Palooka, and the entire 275-page manuscript became my MFA thesis, Fly. It was more than a little weak, however, and I subsequently attacked it with a pen, markers, highlighters, and anything else to move hard-copy paragraphs from chapter to chapter and front to back. I trimmed it down to a not-so-well written 50 pages. That version, Curious Men, received some decent reviews, but the primary response involved readers wanting to know more. That can be both good and bad, and in this case, way bad. I was never satisfied with the work; I could not capture the excitement—exhilaration really—and anticipation at just twenty-years old, followed by confusion and disappointment. For me it became the quintessential “you had to be there” narrative. The true story goes to emotional extremes, pulling this nineteen-year-old boy out of some catatonic state and into some woke existence of adventure and exploration. The written version, well, didn’t.

Long story short: the long version was way too long, and the short version left people longing for more, indicating I came up short. I can’t get it right.

Honestly, I have been thinking about, writing about, messing with, focused on, and ignoring this story for forty years. I long ago decided that I would never get it right, figuring it would be wrong to put it out there. I have letters, maps, notes, journals, emails, and a half dozen different versions of the same manuscript all saying the same thing, and not very well.

Until last month. On a drive to Florida I listened to the audio version of Beryl Markham’s West with the Night. I enjoyed this version of the book I had read several times decades ago, but somewhere while driving past the dilapidated and very incorrect theme park, “South of the Border,” in South Carolina, my mind drifted back to my manuscripts. And on I-95 South I figured out exactly how to start, what to focus on, and I finally understood the problem I’ve had all along with the narrative: It isn’t about anyone else’s journey, it’s about mine. The book is not about the character I had been writing about for forty years; it is about me; I’m the protagonist.

When I got home, I pulled out the long, bound version that was my MFA thesis, as well as the short version in a binder on the shelves behind me. I pulled up the published versions which focused on one segment of the story, and I reread the longer version, Curious Men, and sat back knowing two essential things: First, they all suck. Second, I know now exactly what I need to do to unsuck them. My energy has returned, some internal motivation has been reignited.

It was a four-hour session that first morning I did little more than read through pages and chapters with a fine-tooth comb much like the NY Times editor must have when he first received the Pentagon Papers. What I believed was a story no one would care about and which I was not telling well at all, I finally knew exactly how to tell so others would be interested.

It was both exhilarating and terrorizing. I am ready to get back to this and get it done right this time, yet doing so means not only facing the possibility of not getting it right yet again but also dealing with some realities I’d almost rather let lie dormant.

But if my trip to Florida followed by an inspiring trip to western New York ignited some spark, it would be just a few hours later that some bomb exploded in a manner that sent those proverbial chills up my spine.

Long story not so short:

I received a message that very afternoon; I mean I closed the manuscript, got in the car to get a Slurpee, was sitting in the parking lot thinking about the protagonist of the work, me, and I received a message from the sister of the subject of my book. Be clear: I had never heard from her before in my life; I did not know she existed. Yet, she messaged me the very afternoon I had started work in earnest on a book about her brother.

She said in part, “My name is Kim and I just read online one of the stories you wrote about my older brother. I never knew him, he left with you that last time when I was five, and I am now almost fifty. I saw online you are a writer now and I am wondering if you plan to write a book about him.”

Again, that message came just hours after I decided in earnest to get back to it, my desk covered with pages and maps and journals and emails. Insert Twilight Zone music.

Kim wrote that she remembers the leather coat in a picture of him with me and a friend, Annemarie. We’re in a hallway at the college, laughing. She remembers him dropping her off at kindergarten the last week she saw him, and her teacher asked if the man in the car was someone else he happened to look like. She still has an old, worn sweatshirt of his he left behind. I asked what made her write me that day and she said their oldest brother George had recently died and it got her thinking about her other brother who was long gone, and so she found me online and messaged me.

I told her about my day up until then, and she agreed it was more than a little freaky that she chose to write me that day. Strange, but when I read her message, I didn’t picture a fifty-year-old, but instead a little girl.

The most difficult part of writing is getting started. In this case, I started more than a few times, and each complete version begins differently. Chronologically, the story starts in Virginia Beach in the mid-seventies. For narrative sake, it starts in February 1980 in my small dorm room. If I want to put a “hook” at the front, it starts a few years later seven thousand miles southeast of here in a then-peaceful, not-so-small-anymore village in what is now one of the most volatile and dangerous places on the planet. In a few versions it starts with a nightmare I had three or four times—same one—that woke me up. In one version it starts at the end and works its way backward.

None of them worked.

But when I think of that time, that experience; when I recall the “me” of back then and the life that I had, the energy and motivation and confidence I had then; when I think of the times I’ve told this story to others, my thoughts always go directly and immediately to one place: Antonio’s Italian Restaurant on Route 417 in Allegany, New York.

Last week I was in western New York, and I walked along the Allegheny River, followed a path through the woods, and remembered my life in that very spot almost forty-five years ago. I felt younger and vibrant yet somehow tired and disillusioned. The perfect combination for a work of creative non-fiction.

So that is where it starts. Time to wake this narrative back up so I can put it to bed and send Kim her own copy of a book about her brother that in the end isn’t about her brother at all. It truly should not take forty years to finish writing a book. On the other hand, some books, perhaps, should not be written at all, and that may well be the case here.

I have learned that sometimes it is best to not search too long and too deep for a resolution to the narrative, and that in real life sequels are rare. But I’m a naturally curious person, and it seems to me now that Joseph Conrad was absolutely correct: “Curious men go prying into all sorts of places where they have no business.”