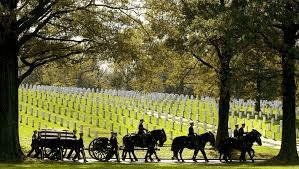

When my Uncle Tom Burton died, the service was held at Arlington National Cemetery. He was a war hero, then a sheriff, always a father and a fine man. He lived a long life and it was an honor to be there when a marine knelt in front of my cousin, Audrey, and whispered, “On behalf of the President of the United States…” and guns were fired, and a soldier stood amidst some headstones and saluted the entire time. Nearby a horse-drawn carriage waited.

I walked about the cemetery that day and noted the names and dates, and while many of them did indeed die in combat and were interred at Arlington, many, such as my Uncle, served his time and lived a good, long life–never long enough, of course–and played with his grandchildren before that inevitable day. I wrote about Arlington Cemetery for the Washington Post, and while sadness was a motivating factor in my prose, it was not nearly as present as was pride for the women and men who served.

Staff Sergeant Edward L. Miller of the 309th Infantry, 78th Division, from Pennsylvania, was never buried at Arlington. Killed during the Battle of the Bulge, his final resting place is in the American National Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands. His is one of more than 8000 soldiers buried there beneath the white crosses with names carved in perfect formation. The grounds of the cemetery–officially American Territory about two hours southeast of Amsterdam–are manicured and, in April, spectacular for the flowering trees and freshly mown lawns. Sergeant Miller’s niece, Kay Miller Debow, with the assistance of the abundantly friendly and respectful staff of the cemetery, made a rubbing of her uncle’s stone. After, she rubbed sand from the beaches of Normandy into the letters of the familiar name, washed the stone, and stood back to note how Edward’s name now stood out from the rest of the whiteness. What an honor it was to be there, to be part of this journey which began across the German border more than eighty years ago, and which continues with relatives who do not want their sacrifice to be forgotten.

In fact, honor was the word most exchanged in Margraten that day. The staff commented several times that it is an honor for them to care for the grave of the men who protected the country from the Nazis and liberated them not long after Edward Miller’s death. Kay commented what an honor it was to meet the people who look after so many fallen American’s, and the family who cares for his grave drove to meet her and brought flowers for her uncle and said it has been their family’s honor to be able to do so since the end of World War Two.

I don’t hear the word honor anymore. It was an emotional day for the obvious reasons, but also for what no longer seems to be so common: honor, respect, sacrifice, gratefulness.

It was a beautiful day; clear blue skies and a soft sixty degrees. I’ve known Kay since we were young, before the world slipped into our lives with all of its competition and anger; before Kay’s own service in the United States Air Force, before the world invented a way to sit at a table, logon, and find fallen soldiers, back when Sergeant Miller had been gone just forty or so years. That was a lifetime ago. Several. And I looked out at the crosses and wondered how many families in the States take the time to come to this remote, country town to pay their respects to someone who never made it home again to see their mom; never returned home again to get back together with an old flame and get on with their lives; never saw the sunsets and distant beauty of a morning mist.

Still, I could not understand why this was so much more emotional than the internment of my own uncle at Arlington. Then it struck me as I watched Kay place her hand on Edward’s headstone while no one was nearby: She never knew him. I knew my uncle; we laughed at parties together, and he showed up at my parents’ anniversary parties and always laughed with us, told stories. He died when my son was already in his twenties, and when my cousin’s kids were adults. Edward Miller died when his brother, Kay’s own father, was still a child.

Eric Van Heugten, the man who brings flowers to the grave and whose family has done so now for eighty years, stood next to me along with our host, Roel Timmermans, as I looked about and said, mostly to myself, “These men were the same exact age as my students.” That is what I couldn’t shake. That’s the difference. When I’m in class and my students are reading their text messages or staring out the windows, I look at them on the front edge of their lives, many of them living away from home for the first time, and they are the same age as the soldiers beneath the soil of Margraten. Eight thousand of them. More. Eight thousand men still teenagers and in their early twenties who never chose a major, never asked anyone out, never got back in touch with an old friend and said, “I’m so glad you’re home.” Because when someone you love goes to war, you simply don’t have a clue if you’ll ever see them again, and it’s terrifying.

And I don’t think my students understand that, or even understand the honor it is to be alive at all. I wish I could bring them all to Margraten, or the American National Cemetery at Normandy, or any of the other thirty-one cemeteries in seventeen nations which forever hold the remains of men who just learned to shave, just learned to drive. Just fell in love.

RIP Sergeant Edward L. Miller. You’d be proud of your niece and all of those who served with her in yet another war, this one in the Gulf.

Vocabulary list for my very-much-alive twenty-year-old students: Honor. Sacrifice. Gratefulness. Loss. Mortality. Love.

Love.