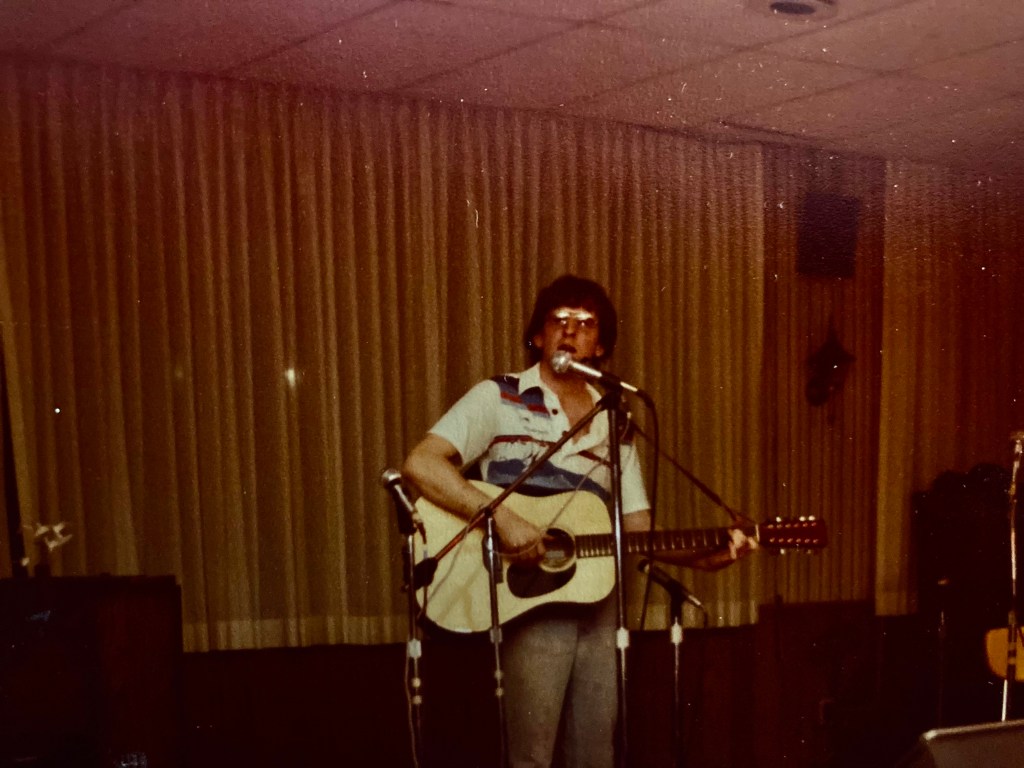

That’s my friend Dave Szymanski. He died Tuesday, May 14th. RIP my brother. We laughed so much that now just laughing at all often makes me think of him. We were going to get together when we both turned seventy and sing “Bookends” on some park bench. No kidding; it was part of the plan. We wanted to belt out to whatever audience was out walking their dog, “How terribly strange to be seventy!” Well, that won’t happen. Still, I am absolutely certain if I make it that far I’ll most definitely do just that, but alone, crying, laughing. I have so many stories about Dave you’d think we were twins. But those are mine now–Dave and I agreed to have joint custody of the stories of those times, but since he is gone now, I’m assuming full ownership. Unfortunately, they fall squarely under the category of “You had to be there,” so there’s no point in sharing them.

This is not likely to go where you believe it might go.

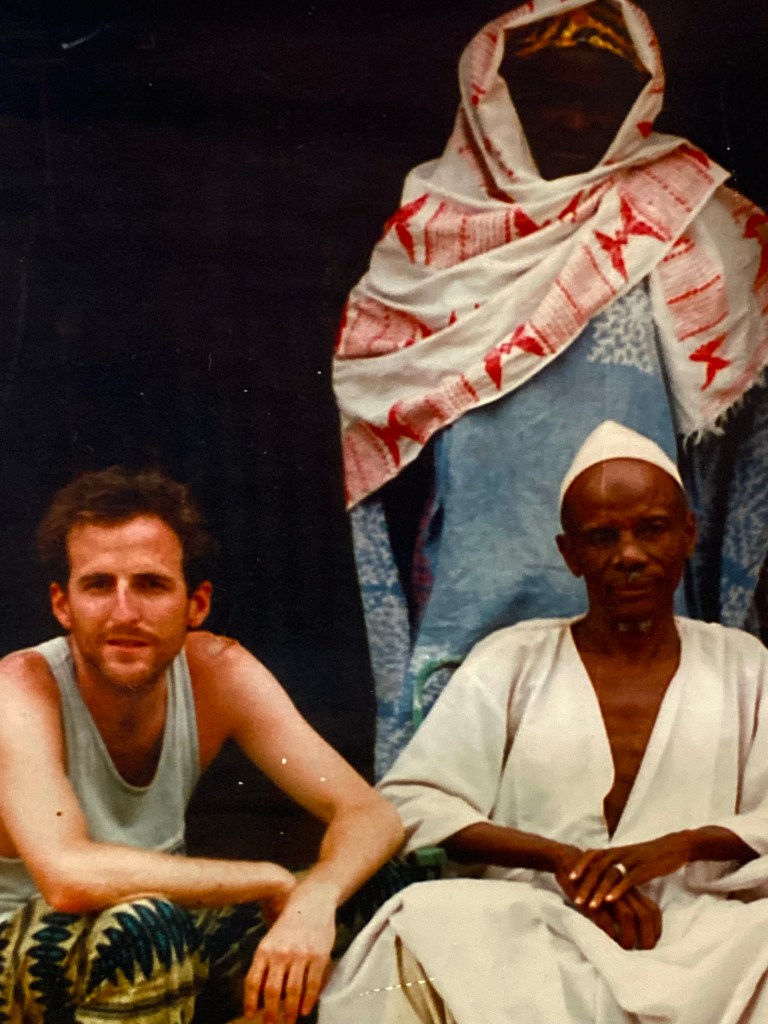

I’ve been thinking about what I can best call the start of some independent consciousness–that is, the time when I was first aware I was a growing, independent thinker/dreamer, mentally unattached to others, my thinking not entirely tethered to parents or siblings or teachers. I guess I was in what we then called Junior High, now Middle School, and at thirteen or fourteen years old life was still idyllic. That’s the point I think I started to think of myself as an individual. I have no idea if that is late, early, or disturbed. We lived near the Great South Bay next to a State Park and an arboretum, a golf club, and I was surrounded by friends in the village of Great River. I have memories before that, and possibly even dreams, which at that time were to either be an astronaut (Apollo 11) or play baseball during the summer (Miracle Mets) and be an ice cream man in Florida during the winter. But those were the “in the immediate” aspects of life; that is, things you thought about and said to friends but then forgot nearly instantly. But realism crept into my view somewhere around seventh grade when more realistic plans surfaced, like sailing around the world or riding my bike across the country, or being a musician or a writer or a tennis pro. All seemingly real plans at the time; those things which you no longer imagine and pretend but which you pursue, even if fruitlessly and without much talent.

No one save his family knew Dave was sick, so most of us didn’t have the chance to take the time to reminisce. It’s important; we always say, “Tell people how much you care about them because you never know if they’ll be around next week,” but we rarely follow through. We know it is true, and we know it is real, but we just don’t. But if we really did know it was the last time we might talk, the last chance to say something, like how much you appreciate the long conversations in the radio station at five in the morning, you picking out albums, him tearing UPI articles for the news; or how the three am pancake house runs were more important than final exams; or how the weekly texts through the next forty years kept you going, you’d tell him. Listen: Please, make sure if something happens and you know you’re going to be checking out, do not keep it a secret; some of us have a few things to say.

Anyway.

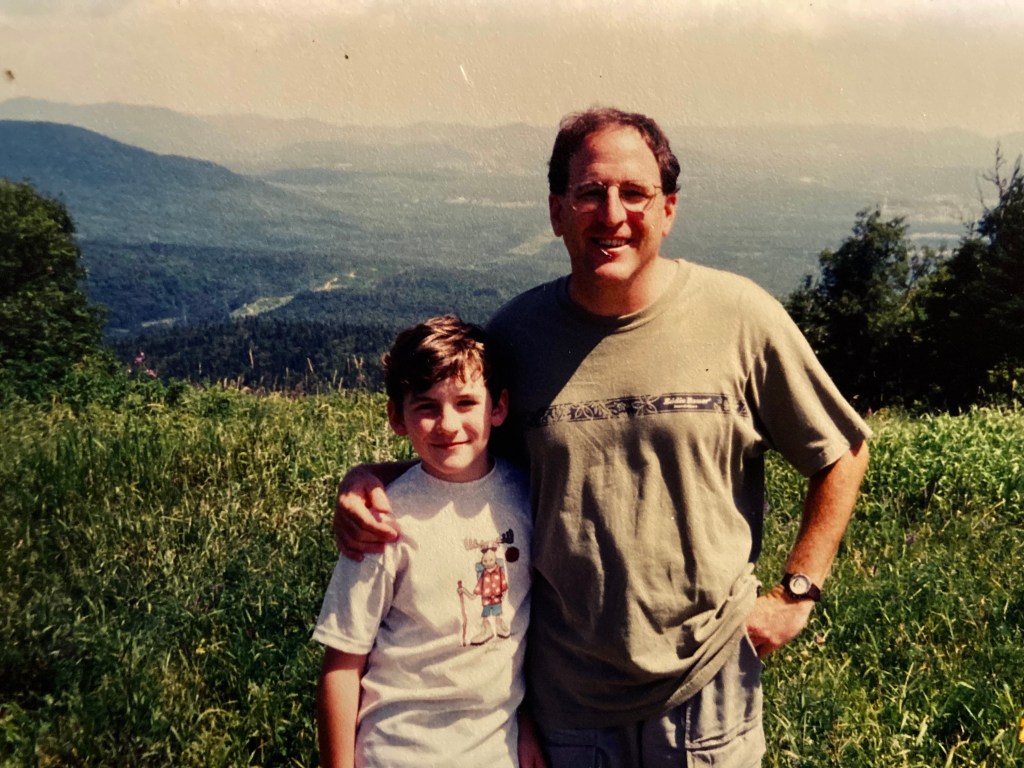

A few days ago someone asked me for my favorite picture of Dave. I went searching deep both on and offline, but I do not have many at all since back when we spent a lot of time together we rarely walked around with a camera and film. But I looked, all the while sifting through tons of other photos of the scattered years throughout my life, and at some point I stopped and simply sat remembering, and I realized something close to lifesaving during an otherwise heartbreaking week: What an amazing ride this has been so far.

I’ve mostly taken the paths of least resistance, I must admit, but apparently someone was up ahead clearing it for me, because it’s been outrageously fortunate. And I finally figured out what the pictures are for. Not only to reminisce, but to remind myself when I get lethargic or depressed, lonely, or tired, that I’m still walking this brilliant Camino, and to remind me of the words of Virgil when he wrote that Death twitched his ear and whispered, “Live….I’m coming.”

Not knowing when someone is going to die, or even that they are sick, is a cold reminder that we don’t know when we’re going to die, or when we might fall ill, and the truth is we just might have a few things to say to those we will leave behind. Speak now or forever…

I normally try to not write too directly only about myself, choosing instead for a digression into some common ground. But not this time. Honestly, this one is for me. Just a few findings from the journey so far:

Call someone. Tell them something. Anything. Forgive them. Ask them to forgive you. Tell them you’re sorry you didn’t answer the phone that last time they called and said they felt like talking. You planned to call them back but just didn’t “feel” like it yet. Now you can’t. Go ahead, call someone and say you wish you were as good a friend to them as they have been to you. Don’t be embarrassed. It’s only life, you know. That’s all.

It’s only life.