One:

Two:

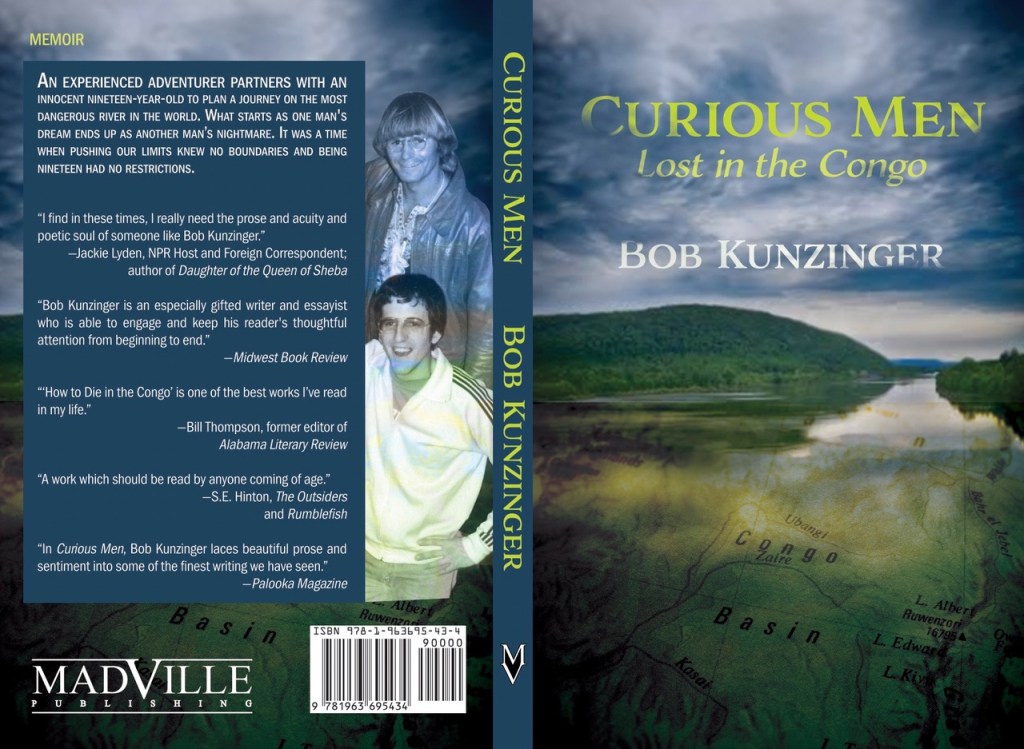

CLICK ON THE BOOK COVER BELOW TO ORDER:

This work was originally published in “Barely South Review” about twelve years ago. It has since been anthologized and often pops up around 911.

“Death plucks my ear and says, ‘Live. I am coming. Live now.'”

–Virgil

I went to the local hardware in Hartfield and bought a sickle—a huge rake-like piece of

steel only instead of a rake at the end there is a double-edged sharp, wavy blade made to rip

through branches, thick weeds and other bone-like growth. Eighteen dollars.

The front of my property is wooded, and on a few acres toward the river, I spent some

time clearing out brush and unwanted vines. I piled it up to haul away, but before that could

happen, other more tenacious weeds—small trees really—took over the area. Some I pulled out,

some I mowed, but I couldn’t grasp to tug out the tougher ones—so the sickle. One warm

morning while alone I put on shorts and flip flops, grabbed the sickle and walked the six hundred

of so feet through the woods to swing away at a small grove. None would rip out easily, so I

aimed for the fences, came down from my right with major-league force and tore through the

vines like an axe through balsa. I attacked one after another, muscles taught so that sweat came

fast, and I made progress. Then I stepped to swing at what looked like a thick, knotty growth at

the bottom of the stump. It was a Virginia creeper vine. Sometimes these monsters look rooted

but aren’t. But what do I know; I’m from New York. So I swung at it like A-Rod. The blade

passed through as if the weed were nothing more than a figment of my imagination, and with all

my energy plus a good deal of inertia, the metal blade ripped into my left ankle.

I like flip-flops. I grew up on the beaches from Long Island to Virginia, so I’ve been

wearing them since I’m a kid. I actually had one pair for ten years, sometimes rigged with a thick

paperclip to hold them together. My feet from April to October have a thick white stripe across

the tops seen only when my flip flops are off. I teach in them. I walk in them. I even mow the

lawn and chop wood in them. Despite what many have said, they are not the cause of the blade

Tarantino-ing my ankle. I don’t remember my foot slipping. I do remember almost not going out

to cut the underbrush to begin with because I couldn’t find my flip flops. What a different story

this would have been had I not come across them on the back porch.

When it happened, blood exploded like water in a hose that’s been held back by bending

and then released. My ankle, foot and flops looked as if dipped in bright red paint. I hobbled the

six hundred feet to the back of the house to wash off the wound, bandaged it, then went back out

to cut more wood; I was wired from adrenaline, my ankle didn’t hurt too badly, and to be honest

I had a lot to do.

That night I iced it. I kept it clean. I was fine. Really.

A week later my leg was pitting a bit when I pushed my thumb into my shin. Excess fluid

I figured. Prior to the whacking, I had been running up to eight miles a day, prepping for the

Rock and Roll Half, so one evening when I was feeling a bit more hyper than usual, and the

swelling moved to both legs—a feat I could not comprehend from injuring one ankle, but I don’t

have a medical degree—I stopped at Kroger and spotted a blood pressure machine. This can’t be

right, I thought, when the first reading came up 270 over 190. I did it two more times and both

readings came pretty close to the same. At the checkout I let them know the machine was

broken. We all laughed at my numbers—even the bagger laughed and put the laundry detergent

on top of the bread. It was that funny.

The next day, worried about my ankle, I washed off my flip flops and went to the doctor.

He took my blood pressure. Again. Again. He asked why I was stupid enough to wear flip flops

while doing yard work. I pointed out I wacked myself above where any shoe would have come

anyway. He asked if I were doing cocaine, heroin, or any other substance, asked if I had

shortness of breath, dizziness, if I had thrown up, fell down, or otherwise felt corpselike. He took

my blood pressure again. He asked how long I felt hyper. “Years,” I said, and he took my

pressure again. Then he sent me to the emergency room. Average BP—260 over 175.

Tests. IVs. Tests. On and on it went for several hours. Nurses came, two doctors stopped

by, some punk there to visit a friend who had overdosed came by to check out my vitals because

my blood pressure was the talk of the ward. The nurses upped the meds. Finally the doctors said

based upon my blood vessels behind my eyes and various tests, my blood pressure had

apparently been that high for probably some years, and that if it wasn’t for the fact I’m totally

healthy otherwise with excellent results from blood and other tests, I’d have had a major stroke.

I asked the cause. The doctor shrugged. Genetics; in a high stress situation for far too

long; a combination, he said. They brought it down to 190 over 95 and sent me home with meds

to bring it back to normal. They told me to keep exercising and that because of my medicines I

could do the marathon, but to be clear, I’m going to be very weak for awhile until I adjust to a

life where I’m not pumped on triple doses of double shots coursing through my veins.

A few weeks later at a follow up where my pressure was at 110 over 70 the doctor told

me in complete agreement with the cardiologist and another doctor, had I not gone in, I’d have

most likely had a major stroke trying to run the half, and probably would be dead. I asked why I

didn’t have one while doing the eight miles a day prior to the Great Sickle Incident, and he was

quite professional about it: I don’t know, he said. I really don’t know. You should have. Good

thing you wacked your ankle, he said.

Yeah, thank God I wacked my ankle. And I thought how often that happens. Good thing I went back for the keys. Good thing I stopped for coffee. Good thing you kept me on the phone, or I’d have been at that intersection just at that moment.

“Good thing I watched Monday Night football on the 10th and overslept: I work on the

85th floor and I’d have been right there,” the stock broker said in the street to the television crew.

As the towers tumbled, he counted his blessings.

Good thing Larry Silverstein, owner of the lease of the World Trade Centers, has a wife

who made him go to his dermatologist appointment that morning instead of yet another meeting

in the North Tower.

Good thing Chef Michael Lomanoco of “Windows on the World” broke his glasses and

had to stop at Lenscrafters that morning to get them fixed.

Good thing Lara Clarke stopped to talk to her friend, actress Gwyneth Paltrow, in a

chance meeting down in the village that morning making her late for her job on the 77th floor.

Thank God singer Patti Austin, booked on flight 93, had to leave Boston a day early

because her mother had a stroke and she had to get back to San Francisco on the 10th instead. “I

went back and forth all day about when to leave,” she said.Thank God actress Julie Stoffer and her boyfriend had a wailing fight that morning and

she missed Flight 11.

Actor Mark Wahlburg is still haunted by that same Flight 11 to LA, which he missed at

the last minute when an 11th hour invitation to a film festival sent him to Toronto instead. He has

nightmares thinking about who took his place on the flight. He would have been sitting next to

Family Guy creator Seth McFarland who also missed that flight when his manager gave him the

wrong boarding time and he was fifteen minutes late. He, too, still has bad dreams, he says. But

thank God, he says.

It’s chance. It’s the phone call, the caught light, the traffic backup. It’s changing your mind. It’s

sticking to the plan. It’s oversleeping, insomnia, an upset stomach. It’s a few seconds. It’s the

wrong shoes. It’s the stroke of luck.

The Shed was twenty-feet deep by eight feet wide, with two windows, two lofts, double doors, and sturdy enough to withstand everything except Hurricane Isabel.

Of course, I bought the shed to hold supplies when I was building the house. Before I started, when I had first cleared the small portion of the property for the home, I had this shed delivered figuring I might need to sleep in during bad weather while up here for three of four days in a row seventy-five miles from the place in Virginia Beach. Michael and I went together to the shed place in Virginia Beach. Some guy paid for it but never picked it up so I bought it brand new for a song and the father and son team I bought it from delivered it seventy-five miles, across the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, across the still-narrow Coleman Bridge, the Piankatank bridge, and down my winding driveway through the woods—for twenty-five dollars. I also bought them lunch.

It didn’t take long, as it tends not to take, to have stories to tell from the shed.

Back in ’99 we had fifteen inches of rain in two days and the water ran from the river side of the property down to the woods beyond the shed. I had the shed leveled off the ground by about eight inches on blocks, so the water rushed toward the door but instead dug crevices under the shed. The shed, miraculously was dry, but impossible to get to.

Isabel didn’t do a thing to the shed, but she knocked down thirty oak trees here at Aerie, and one of them lingered for weeks right above the shed. I knew it had to come down but this was a job I couldn’t pull off myself. Scavengers wanted more than fifteen thousand dollars to clear the fallen trees, so I said I’d do them myself, which I did, but I was afraid to cut the half-fallen tree in fear it would crush the shed. Instead, another storm just a few months later cracked the trunk and it crushed the back half of the shed for me. I remembering thinking, “Hell, I could have done that.”

So in the lemonade tradition, I made the back half into a greenhouse with plastic sheets for the roof, but it didn’t really work, and over time the mold and mildew and various snakes and wood rot got the best of The Shed. It took about twenty-seven years.

One time early when Michael was about five, we played hide and seek as we often did, and I ran in the shed while he was still too far away to follow me right in, but he could see me. I then climbed out the back window and settled behind the back wall. I heard him come in the shed and was quiet for a minute then said, to no one in particular, “Holy Cow, How did he do that? Daddy?”

I remember how we laughed.

We built things with wood and made signs and birdhouses. None of them were well done but they were all perfect. Occasionally we’d take a break and play “Voices.” That is, we’d recreate “Wind in the Willows,” and I was the voice of most of the characters—Badger, Toad, Moley, even the stoats.

And we kept the sporting equipment in there and played frisbee, football, golf, and ring toss, which we still do nearly thirty years later when outside barbequing.

The bikes he kept in the shed got bigger, and the toys were relegated to the loft while more accessible spaces were reserved for tools, chemistry sets, then inflatable kayaks and eventually equipment to hold his art supplies and frames.

When he was little, he would tie me up in a chair with a lasso his uncle sent him from Texas, and he kept lizards and frogs in tanks until he couldn’t feed them anymore and would let them go behind the shed, in the woods.

He kept buckets of fake snakes and lizards in there when he was young, and when the roof collapsed and water raged in, it carried the rubber reptiles out the door and under the shed. The next day I spent an hour reaching under the shed and pulling out the toys, until one reach pulled out amongst the fake snakes a real one with red and yellow and black, and I forgot the rhyme about poisonous snakes so I just threw everything as far as I could.

There were other days like that.

But there’s a hole out there tonight. And Michael is in Ireland, far from the fallen shed. It had to come down. I had to do it now or we’d be still out in the still standing shed telling stories.

I destroyed the last of it a few hours ago, and I rested on the nearby patio remembering the times we shared for his entire life, and the talks we had—so many talks we had safe in the shed, just the two of us, about growing up and traveling and things that frustrated us, and things we were scared of. Out in the country like this along the bay when a father and son go into the shed, usually it is for some form of punishment, “a whooping” as they say. Well I never had a reason to punish Michael; but we did have plans to make, so out to the shed we’d go, and he’d make notes on wood with a nail, and we’d plan adventures like training across Siberia or walking across Spain.

We kept tools in that shed, and mowers, bikes, grills, and more. And memories filled the spaces between everything else. We let a lot of memories occupy that space.

Funny though. I sat out there today when I had finished knocking it down and thought about the next week or so during which I will haul away the remnants, clean up the ground, lay down some field stones and mulch in front of a much smaller, new shed, put a few chairs and a small table there, and I tried to imagine the new way it will be, and it made me a bit sad, of course, but excited for a new place to talk. But lingering a bit in the hot afternoon air was the sound of ten-year-old Michael playing his harmonica and the distant hint of his unchanged voice asking if I want to play hide and seek.

There are some things that shed kept safe for us I’ll never be able to destroy.

Now:

Next:

I rose early this morning since I needed to be in Norfolk by 8. That’s okay, though. I am drawn toward the early morning hours of dawn when I feel ahead of the world, and I can sense some small hint of hope. The geese flew by headed to the river, and to hear life around the water in those moments motivates me. Before the sun rises, often just after the first sliver of light reaches up across the bay, I can hear osprey and other sea birds who at that hour never seem to mind my presence.

But earlier, when that glimmer on the eastern horizon is still merely a possibility, I have taken to walks by moonlight, sometimes not even that. In the woods where I live and down along the water, something is going on. There is life out there wide awake and moving through the dark hours like spirits who need to finish their errands before the sun gives them up.

Fox come about the edges of the woods looking for scraps of food or the peels and rinds of bananas and melons. I can stand patiently off the side of the drive and one fox will wander across the yard from the woods behind me to those on the south and stop before disappearing again beyond the laurel, and he will stare at me, relaxed, nosing around the base of a tree where I occasionally put food. Then he’s off—not swiftly or in fear, but nonchalantly, demonstrating that he lives here as well and has decided to stretch his legs. That’s all.

Owls, too—some barred but mostly screech owls, perch in the oaks and elms, sometimes swooping down and moving through branches with precision. But my favorite are the geese which cover the night sky in flocks sometimes so enormous the swoosh of their wings alone creates a breeze, and their call to “Go! Go! Go!” is startling.

Closer to home, out front near the edge of the trees, deer nearly always feed on the dew-soaked grass and often the hostas, and if they sense me sitting on the porch or standing in the clearing, they will look up, briefly, ears turned forward—just for a moment—and then return to their grass, not minding me, aware just the same.

And it is then, when I am well acclimated with the night and my eyes have adjusted, and my soul too has adjusted, that I think of my way in the world, the motivation behind the turns and hesitations, my purpose of this passing in time. Oh, do I ever have an internal monologue underway with long-gone friend now gathered in my nocturnal imagination. There’s Cole nodding his head and insisting I follow my own path. I can hear him clearly when I’m out there, see his small sardonic smile as he says, “Come on Kunzinger. You know how to do this, stop waiting for approval or it’s never going to happen.” And there, too, is another friend whose smile is as wide as dawn pressing his sense of adventure into my spirit with an “all or nothing” carelessness about him which brings me up short yet livens my ambition. In one brief moment I am eased by no longer thinking of them in the past tense, but just as quickly, we all move on; usually just as the sun surfaces.

The sky in the distance across the reach lightens ever so slightly, from dark, almost Navy blue to something slightly more pale, like powder, and I’m alone again—the fox rushing off into the woods, the geese at rest in the harvested field or at the river’s edge, and the murmurs of chickadees and wrens and cardinals chase away what’s left of the stillness, and even my friends bow off, and I have trouble separating memory from imagination. So I get in the car and head south to the city where I simply don’t belong.

It’s as if time offers a small reward for some of us who stay up late or get up early to gather as much out of our moments as we can. Then, just briefly, it eases me back into this new reality I never anticipated. It remains for me the most honest time of day, the most just, when all thoughts have a chance of pushing through the darkness, and the truth about what we are here for is ironically illuminated.

I’ve started to live for the deep hours of the night at the twilight of dawn.

Memory is as fluid as anything in our lives. What happened and what “seemed to happen,” as writer Tim O’Brien points out, can often be confused. When looking back we might have a habit to recall what seemed to happen, reality having been washed and hung out to dry over the course of decades. Sometimes though we can recall nearly ever nuance of a time in our lives for its significance, its uniqueness, or its romance. I have a pretty sharp memory when it comes to many events. A friend of mine and I were talking not long ago about how we can both remember nearly every detail, everything, about a period in our lives so long ago you’d think it was from another life. Many of us have times like those which, for whatever psychological reason, we can summon up to the point of remembering the clothes we wore on a particular day.

My basic memory for most things is pretty solid. I remember all my phone numbers and license plates, and, worse, the phone numbers and license plates of friends of mine. The old joke about song lyrics holds true with me, but so do the times spent with extended family. One of my only memories of my paternal grandfather was him weeding a lot he owned next door to his house on Long Island. He died when I was five, so I was no older than that, probably still four. But I picture that day, those moments, perfectly.

Some years ago when Meanwhile in Leningrad came out, someone asked how I can remember the conversations I had with survivors of the Siege of Leningrad, who at the time I knew them were in their eighties, and I wrote the book several years after our conversations. I said, well, first of all, they’re never going to find or read the book, so there’s that. But more accurately, when a woman sitting on a bench holding my hand tells me about dragging her dead husband and son across the city to leave in a mass grave, and she sat with me clinging to their photograph sixty years later, I will not forget any of it. Much of the writing in that book falls in that category. Did the conversation happen verbatim? Doubtful, but the gist of it is pretty damn accurate. There’s an old journalism method that when you write the piece and include quotes from someone, call them up and read what you wrote to them and ask, “That’s pretty much what happened, right?” Nearly all the time they’ll say yes. Can you remember the words, exactly the words, you spoke an hour ago? Exactly. If that’s not possible as in this case, I rely on memory and notes.

Memory is reliable or not depending upon just how present we are during the event. That time so long ago when we said we could remember everything: We were both very much present at the time, we lived the example of what would later be called “mindfulness.” Of course we remember. Likewise there are times I so shut out of my memory it’s like they never happened at all.

Still, some events are so close to my soul I would need the team from Matrix to come extract them.

Like what happened in 1980 and 81, when I was a freshman and sophomore in college, the subject of my forthcoming book, Curious Men, from Madville Press. Of that time then, I remember everything. I watched, studied, and listened so intently that this memoir could be considered a documentary for how clear the details remain to me four and a half decades later.

I like that “memoir” includes the Spanish word “oir,” to hear, because much of memory stems from what we hear, and as a nonfiction writer I am bound by listening to the world around me, sometimes to the one sitting in front of me, and those sounds of vowels and consonants and the musicality of language I know will never escape my recollection.

My friend, colleague, and former officemate, Tom Williams, once introduced me at a reading as a non-fiction writer by saying, “Here’s some shit that happened to Bob and the best he can remember of it.” That’s pretty spot on. Despite a degree in journalism, I never had what it took to do the job in the traditional sense like so many I graduated with, some of whom have won prestigious awards for their work. I was definitively not up to that task. But I could handle the feature work, the “Let me tell you what just happened to me” work, just fine. In college, my friend Deb used to help me with news stories and I’d help her with features. We knew our strengths. I had a column in the college paper for which I ventured out into the community and did something, and then I wrote about it. I went horseback riding in Machias, New York, flew planes in Wellsville, kayaked the lake in Allegheny State Park, and sat on the ground behind campus at Merton’s Heart. Those events I could remember. I knew how to be present. Most of those activities were out of my wheelhouse at the time, so recalling what happened was easier. I was paying closer attention, sometimes just so I wouldn’t die.

Memoir is like that. If we can’t remember it we’re certainly not going to write about it.

But not this time, not this book. Summation: As a college freshman uninterested in the normal activities of my floormates–that is, drinking and drinking–I felt lost and disconnected from everyone. Then a family friend returned from the Peace Corps and asked me to help him plan a trip, solo, on the Congo River. So I did.

Long story short, it didn’t work out and his trip became mine. The first half of the book takes place in western New York. The second half in the Congo.

Still, that’s not what the books about.

Most of it takes place now, in every classroom across America where nineteen-year-olds sit and try and find something worth doing, something that reaches deep inside them and wakes them up. I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty-six years and one thing hasn’t changed: they’re scared out of their minds. They’re alone in a new place far from home living in a room this size of their car with a total stranger, and every adult within earshot constantly wants to know their plans for their major, their careers, their lives. It is often unbearable.

I was exactly like that back then. Until a friend walked into my life and said, “I have an idea. I need your help.”

We were so young.

So that’s what this memoir is about: About that time back then. What we did and how and why we did it, yes, but mostly about being nineteen and far from home looking for a reason to exist at all.

This is how I remember it.

Coming this winter:

I ask my students the same question the first class every semester. I pull a chair into the middle of the front of the room, ask them their names and where they’re from, and we talk about the area, hobbies, majors, quirks, travel favorites, and more. Half the class—I find it a priceless investment in time as they warm up, get to know me and each other, find themselves more able to talk throughout the semester, ask questions, share ideas.

Then I sit quietly for a second and ask them the same question every time:

What are you capable of?

What do you think you are capable of? I don’t mean “What do you hope you can do?” but what tangible proof from previous experiences has convinced you it is worth reaching out a little further than your grasp this time because you know you can do it?

It’s not an easy question to answer because it is difficult to know if we can achieve that which we have not yet attempted, so at best we need to guess. And even the most educated guess is still hypothetical. Yeah, I lose a few at this point, but I usually can reel them back in by jumping that chasm to the goal. “Okay then,” I continue. “What do you wish you were capable of?”

I remind them that unfortunately, every semester the evidence gets worse that freshmen in college are capable of anything other than having technology complete their assignments for them. I insist, then, that one of the finest results of college beyond the degree and the friends and the job prospects is the sense, the absolute pure sense, of accomplishment. To achieve something, to find out we are capable of so much more than we thought, becomes part of one’s bloodstream.

I asked myself that recently, the Capable Question. It was my birthday, sixty-five years to the day after I showed up at the now defunct Shore Road hospital in Brooklyn; one year to the day after Letty “closed the door behind her.” I looked back at what I have done with my life, who is in it and who no longer is, and who is again, and the good news is I’ve been around the block a few times and that’s one thing I always wanted to do. The bad news is as it turns out the block isn’t in my neighborhood.

Sometimes I don’t know where the hell I am. For a person who has traveled as much as I have, I still need direction an awful lot of the time.

So I asked myself, “What are you capable of?” I figure I still have a couple of decades, surprisingly. Maybe more on a good day, maybe just a few weeks when my mind downshifts. But let’s call it twenty years.

I just agreed to a location to perform a one man play in New York. My book Curious Men comes out in just a few months. My book Office Hours comes out in about eighteen months. My fig trees need watering. I’m thinking of getting a new cat or two. Maybe a dog. A goat for sure.

A few months before she died, Letty and I sat in Starbucks at the beach and after a lot of laughing, she said, “I always thought I’d be here past sixty-five, Bawb. I just never thought it would all be over; my life would be completely done at sixty-five.” I nodded. I tended to avoid trying to come up with a response. She didn’t want one. She wanted me to listen, to hear her existence, to be there while she was being alive. After a while she leaned forward and said, “Since I’m not using the rest of me, you can have those years. I trust you to use them well. What will you do with them?”

I thought about it like she had some power to give me twenty more years. “I am going to walk the Camino de Santiago again. I’m going to drive through the northwest for a few weeks. I’m going to take a river cruise in Europe with a friend of mine. I’m going to camp in Havasu Falls.”

“…and?”

The perfect response. “And?”

This is all to bring up a point:

After something I wrote went online about a month ago, several people, some I don’t know, wrote to tell me how good it is that someone my age still thinks I can do something new. They wanted me to know how much they are behind me no matter how outrageous it is that I’d try something besides enjoying retirement.

Two things here: One, I have no idea what they’re talking about. And two, Seriously? I mean, I’m sorry you took a nose dive as soon as you were eligible for Social Security, but I can’t wrap my mind around that mentality. Maybe it’s because retirement is somewhat irrelevant if you never really worked to begin with, but also in the world of arts, in the realm of love, there is no “retirement.” You can’t turn it off, you just can’t. And I want to spend my time with people I care about, seeing things together. I felt the same way when I was in my twenties. Did you guys grow tired of those you know?

“Someone my age” my ass.

I’m not going to republish the litany of accomplishments by people in their seventies and eighties. If you understand then you’re not sitting around lamenting anyway; and if you don’t, you’ll just shake your head.

I have done okay until now, and parts of my life turned out to be riddled with circles, as if Einstein was right—there is no actual “time,” humans have just made it linear so we can comprehend our passage here. Well, I’ve never been good at staying inside the lines anyway.

Honestly, I don’t know what’s going to work and what won’t work from day to day. I just hope for the best for the rest of me.

But, at the risk of being in over my head, here’s my plan: To speak my mind, about love, about hopes, about what is working and what is not. To keep writing as long as I have something to say. To fulfil some plans that I can’t shake.

I’ll retire when I’m dead, and then I’ll close the door behind me. If something should happen to abort those plans, feel free to take the rest of me and see what you’re capable of.

When I was sixteen, I spent part of the summer living in Granville Towers on the campus of UNC Chapel Hill with fifty one other high school students from around the country, including my best friend and tennis partner, Mike Russell. We were there for the National Radio, Television, and Motion Picture Workshop. We learned much about all of these mediums, and we made several films. I knew already I wanted to be a writer and a filmmaker, and some years later was actually accepted by USC Film School during my junior year of college, but I opted out of Southern Cal and headed to Mexico instead. The first of a series of moves to avoid committing to anything.

I’ve always believed eventually we live out our lives as they were meant to be, but not always the way we thought it would happen.

To that end, here’s what happened:

In the fall of 2026 I’ll be performing in a one man play at a theatre in the Catskills. After the three days of performances, a full film crew will arrive and we will spend the week shooting the play in the theatre with all the perks–lights, sound, make-up, sound engineers, and then post-production to turn it into a full fledged, albeit experimental and theater-like movie, which will be sent to Indie Lit Festivals and Streaming services everywhere.

“Front Row Seat” is about a professor on the last day of his career while he packs up his office, and what he files away triggers stories and memories, and philosophy, through his career, including too many tragedies and a lot of laughter. His observation of the behavior of nineteen-year-olds over the course of nearly four decades is a reflection on the changes in society, education, and family life, with always a sliver of hope.

Important note: The most impact this production will have is no-cost distribution to high schools and colleges throughout the country so students understand going in what they need to do and what not to do. These aren’t simply “stories” from an old guy leaving his job. They are carefully composed movements which together expose the deep-rooted aspects of college life that keep students from succeeding. Please help. This is truly an investment in education–as well as an enjoyable play/movie.

I started writing “Front Row Seat” many years ago and I kept adding stories; stories that included anecdotes, like the student who plagiarized me, and one who plagiarized my cousin, the one who threw a desk at me, and the Russian student who freaked out when I spoke Russian to him and he ran full speed out of the building and was never seen again. The brilliant student who became a friend who almost got killed on a study abroad trip only to come home and lose her life to her ex, and the poignant and often horrific stories from military students who came home from war with a different kind of education. There was that paper that belonged to a student who was shot and killed while at work the same time I was grading her paper, and how it took me years to throw it out, and the confrontation with a gang member in the bathroom late one night when I stayed to do my own work. Yeah, I had enough material for a play and a book

Hence, my forthcoming book (2027) Office Hours. But the “performance” part remained, and after several more years of ironing it out and trying out pieces of it to various classes and seminars, I knew it was ready. I’ve consulted with friends in the entertainment industry who, behind the scenes, steer me in the correct direction, and instead of “trying this play thing,” I decided to, how shall I say it, go all in on this. This isn’t me “taking a shot,” at anything; this isn’t getting my feet wet. This is me jumping off a freaking cliff with plans to land right in the middle of the Catskills with a full-fledged, professional film crew, editorial consultants, a PR person, supportive friends. Confidants, really, and a killer script.

So, we’ve started an Indigogo campaign for supporters, including the prized “Executive Producer” roles (the money people), tutors for acting, with still another year to fine tune the material. This is not hotel management or health club management. This isn’t teaching college, though it is about that. This project is a whole new way of life, and it is important. High School seniors and college freshman throughout the country will want to watch this movie. There’s no preaching, just reflection and regret, anecdotes and apologies.

Imagine that; a one-man play on stage in the most artsy community in the country, and a film capturing it all for distribution. That’s my life now. I’m still teaching college, of course. I mean, I could always use more material. But look, I found the people who are the best in their field and can remain a step ahead of me when I explain what I have in mind, and people who all you have to do is make a spark and they’ll burn bright for days on end.

I found the people who know what they are dong.

Something had to change. I decided it would be me.

Click Away:

Something is always missing in my writing that I can’t put my finger on. This is normal, and over the years I’ve had conversations about this with everyone from Tim O’Brien to Susan Sontag; that others read your work and say, “That’s exactly right,” all the while you step away from it frustrated that it is still shy of what you meant, what you know it needs, or worse, know it needs something but can’t figure out what. Welcome to the arts. It’s a like/hate relationship. Love rarely shows up except, ironically, during the conception stage when everything makes sense. But later, well, something is always missing.

More than a few times I’ve been asked to read from older works. My last few books I don’t mind reading from because even though I know I could improve what is there, I’m still satisfied with the material. But when I’m reading a piece from one of the two early books about life in Russia I want to apologize as I go, read a few lines, look up and say, “Geez I’m so sorry this is so shitty,” and then continue, sighing after each paragraph. That’s the nature of the beast–actors too don’t watch old films for the same reason. Perhaps we have learned more since then and we approach the early material unfairly from a more experienced perspective. Or perhaps it really did suck and we just hate to realize it is in print somewhere waiting to embarrass us.

But this: I’ve never read something I’ve written and found material I wished I had not included. It is only what’s missing that haunts me, the untold parts, the “I didn’t say that quite right” parts. And then when I recognize what I should have done, when it is clear to me what really is missing, it can be unbearable.

***

It’s hot today, mid-nineties, heat index about 104. I brought my car to the dealer for it’s check-up and I bought new pillows. I spoke to a friend in Ireland, and I talked to someone in Rhinebeck, New York, about a new project. Then I had to make a call to a friend at a newspaper.

You know, some things simply don’t work out no matter how hard you try. I had planned some overseas trips with people that fell through, and two of three book projects have been delayed. So I took the morning to get stuff done and enjoy a little peace. Then I spent an hour on the phone doing an interview with an old friend of mine up north about the book that is coming out this winter, and we talked about those days back in college when much of it takes place. It was nice to look back.

When I thought the questions were done, he recounted my life for me–the books, some of the jobs, most of the years, as a way of matching my work to my experience. And then he asked something that no one had ever asked before and which never really crossed my mind: “Bob,” he said laughing, almost as a rhetorical aside, “is there any aspect of your life you haven’t written about?”

“Bob?”

I was quiet a very long time, and it came into my caffeinated mind like it had been waiting ready to expose itself, and it was quite suddenly and for the first time for me at least, quite obvious.

“Well. Fuck.”

“Yes.”

It took me awhile to understand what just happened in my head, and I apologized, glad he was someone I used to know well enough to not worry about the dead air between us. It didn’t take him long to decide to remain silent, knowing/sensing I needed to get myself together. He quickly changed the subject but I pulled him back. “No, that’s okay. Repeat the question.”

“Just curious if there’s anything significant in your life that might be worthy of a book or even an essay, but you haven’t written about it and, well, why? Why not?” That’s real journalism right there. We had the same mentors but I was never that good. Damn.

It’s always frustrating when something is missing and you can’t put your finger on it. We all know that feeling, like the song that’s on the tip of your tongue, or the meal you prepared and before the guests arrive you step back and feel like there needs to be one more thing, and it turns out to be the most important element. That feeling. Only this time I had the answer; I know what has been missing, what I never wrote about, though it was never a conscious decision. What’s even crazier is I spent part of that phone silence wondering how no one, no one, through the years ever even once asked about it. Ever. Yet it’s absence now seems so crystal clear, like seeing the two shadowy faces that turns out to be a lamp, and once you see the lamp you can’t find the faces anymore.

“So what you’re wondering,” I replied, “is if I ever consciously didn’t write about something that probably deserved to be written about since everything I’ve ever written has been about me, not to sound egocentric or anything.” He laughed and said my work rarely is about me, that I’m just a character in the narrative. This guy is that good at his job. Our mentor Dr. Russell Jandoli would be proud.

“Is there?”

***

Last year I heard a review on NPR of Tim O’Brien’s book American Fantastica, in which the reviewer said, “This is clearly going to be his last book.” I called Tim and we laughed about it and he said he had heard the review and ironically he was already at work on a new book and now he’s thinking of calling it “Posthumously.” We laughed a long time.

“So you’ve got more to say?”

“Yeah, Bob, but it doesn’t mean anyone wants to hear it.”

Well as just another player in the art world I can vouge for the idea that we all just assume no one will ever want to read or listen to or watch our work; that’s not why we create. But, yeah, I still have more to write about as well.

I’ve been rejected plenty of times. Sure it hurts. Of course I always hoped that “this would be the one.” It would be one thing if I was talking about a woman. That I could get over, and have. But my writing? That’s when it gets personal.

I have known rejection.

I sent an essay to a journal and they rejected it. This is year’s ago. Their brief note suggested they enjoyed the piece but ultimately decided to pass. It was a nice note; no one died in it. About a year later I did a reading at a conference and read that very piece, completely unchanged. After the reading, the very same editor came up and asked if the piece was available, that he loved it and would like to publish it. Not only did he do so, but the work went on to be my first essay noted by Best American Essays. The same journal with two different editors went on to publish four more works of mine, with two more going on to further recognition at BAE.

My point: publishing and rejection can be completely random. It can depend upon the particular style of the journal, or a particular editor, or even the theme of one particular edition, but it can often be equally dependent upon the caffeine intake of whoever read the work, the time of day, the weather, how much it reminds the reader of an old lover, or even whether or not the Pirates won that day. Sometimes essays and poems are rejected simply because the journal already had enough pieces for that time, and other times they’re rejected with great scrutiny and long epistles explaining all the changes that could be made for whichever other journal might publish it, though that new journal may just as easily prefer the essay in its original form. Sometimes editors try and make the rejection letter sound like the literary equivalent of “It’s not you, it’s me.” Get over yourselves, guys. Yes or no?

With a new book launching this Christmas, I’ve been sending out excerpts to journals and magazines. Over the course of the last week or so I was rejected twice, accepted three times, and had two publications hit market. So tonight seemed like the appropriate time to think about my writing. It comes with the job.

Writing has taught me to trust myself and let go of my concerns and anxiety over what others think, how others perceive my decisions. In the writing world, editors can be helpful or random, can understand what they want but not what you do, or appreciate what you do but still not want it. Some like snark, some like drama, some like biting humor and some aren’t happy unless the piece sounds like it was written by some foulmouthed hack. It is essential to study the journal, to understand its history and style, its preference for length and how free one can be with language. In fact, for an editor to suggest in the rejection letter that the writer should first study the journal before submitting is so pretentious I can only assume the editors who make such suggestions don’t know their audience.

Bottom line: Editors can be hacks as can writers. It’s all disturbingly random.

I once sent a piece to a place and it was rejected. A few days later, forgetting I submitted it there because my mind sometimes slips, resubmitted the same piece without changes to the same journal and they accepted it with great thanks. Random. I sent one piece to four different places. This isn’t unusual, but as soon as one accepts it, the writer is responsible for letting the other editors know it is no longer available. Sometimes, though, writers forget and several places accept the same piece. Oops. It helps to change the title of pieces.

I usually don’t pay attention to the comments and suggestions from the readers at journals about how I should change the work they have no intention of publishing anyway. That’s just silly. “Hey, we didn’t like your work enough to publish it but make these changes and we still have no intention of publishing it, but then you will ‘learn’ from us.” Freaks. I do not know them; I do not know their style or ability; and I may be fine with the piece as it is but need to find another journal instead. In the end, I simply need to trust myself or I will forever be second guessing myself. However, once it is accepted, editors suggestions are welcome. Usually. Here’s something: One editor accepted my work but during the proof stage questioned one of my facts. I proposed that when Marie Antoinette said, “Let them eat cake” it was a subtle reference to the fact that bread was too good for the masses. Editorman questioned if it actually happened. After research and discussions, I asked him to just scratch the line completely; it wasn’t that important. But instead, Editorman added the word “spurious” to the sentence, as in “According to spurious account, Marie…” I’m not kidding—I had to look it up. I turned to my friend, Tom, also a writer, and said, “That pisses me off! I wish he had just dropped the Marie Antoinette line!” Not because it wasn’t a good suggestion—it was, but because I’m not the type to use the word “spurious,” and I thought it sounded awkward with the rest of my prose. I think I had a good argument, but it was too late. So, in retribution for making the change without my input, in the four other essays that journal published, I used the word “spurious” in every one.

Writers need to humor themselves with things like this.

My favorite rejections are the simple ones. I received one which read, “Dear Bob, Pass. The Editors.” Perfect. They don’t want it; got it. I understand. That one is crystal clear. I also once received what appeared to be a detailed rejection from a journal which mentioned my piece by name several times in the letter, and which truly made me feel as if they took their time and honestly wished to communicate with me. Then I mentioned it to a friend of mine who is a writer in Ohio, and she revealed she received the identical rejection from the same journal, only the name and title changed in the paragraphs. How do they expect us to take their thoughts seriously?

Last year I received a rejection from the journal which published five essays of mine, but which turned down this particular piece with the suggestion I study their prose style before considering submitting to them and that they expect their writers to read their journal before expecting to be published in it. First of all, the rejection of the essay didn’t bother me; after reevaluating the work I agree it needed much more polishing, and I have since done so and sent it out elsewhere and it has been published. The trouble I had with the thoughtless rejection was that editor’s inability to simply say no. I wanted to write back and say, “I took your suggestion and read old issues to get to know your prose style and, oh, hey, look! You did publish FIVE essays I found particularly excellent–moron.” Instead I deleted it. I delete lots of rejections. I have one friend who adheres to the trend to tape the rejections to the wall and shoot for 100 rejections in a month or maybe in a year, I forget. I prefer to keep the negative crap out of my line of sight. Besides, the implication that the writer did not study the prose style of the journal is condescending. One writer/friend commented I might not recognize the editor is new and the prose style is no longer the same therefore the comment was valid, but that makes no sense. Then why did they send me to old issues to study their style?

But it is the nature of rejection; I’m used to it, both socially and professionally. When the percentage of acceptances goes up, it is mostly because those essays have been rejected enough for me to rework them and then they all do well. It is a numbers game.

I know a writer who for a while every time a journal accepted one of his works, the journal subsequently folded.

Another example: I have a close friend whose manuscript was at a publisher getting ready for publication when a new editor there decided it needed a LOT of changes; “very invasive editing suggestions,” my friend told me. Instead of making the changes he pulled the manuscript and sent it somewhere else which accepted it and published it as my friend wanted it. The work went on to be a finalist for the National Book Award. Editors and readers are like teachers: just because they’re qualified to get the job doesn’t mean they don’t suck at it.

I swear I once got a rejection from a journal I never sent anything to. It was like a “Snoopy” cartoon. I mean, I must have sent them something and simply forgot, but I could never find what I sent them, didn’t have an email in my sent file or a file in my Submittable account, and have nothing on my list of “works submitted” which I keep. Perhaps they just anticipated receiving crap from me and wanted to cut me off at the pass.

A writer’s history with a journal is irrelevant to acceptance. The new piece must stand on its own and it must meet the criteria for the new reading period. But that doesn’t mean the writer started from scratch when the piece was sent. It helps to mention previous successes in a cover letter, especially if some of those successes are the result of publication in that very journal. I don’t know a single writer who doesn’t do this. But like a famous comedian taking the stage; the audience will give you a break and listen more intently for a few minutes, but if you don’t quickly start making them laugh, you’re outta there. A track record with a journal may get you read faster, but that’s about it. You still can’t suck. But neither should the journal treat any writer like he or she is a moron. Just read the damn thing and Pass or Accept.

I have no idea what my win/loss record is at this point. Better than the Mets I’m guessing, certainly better than the Pirates, but really, I stopped keeping track. I think it’s pretty good. Mostly that’s because I do a fine job of rejecting my own work several times through scrutiny before I decide it is ready to head out on its own. I don’t believe writers should listen to the advice of anyone who criticizes the work unless the writer knows and trusts that person. I have a few I trust, very few. Of course, finding someone to criticize the work is as easy as finding a relative to praise it. In the end it is a waste of time trying to “improve” through blind criticism. You must know and understand and trust the person who makes suggestions. And this isn’t because these other people don’t have something beneficial to contribute; they very well may.

The list of famous rejections is out there; check it out. You’ve got to be one hell of an accomplished writer to make the list of famous rejections, and I don’t play at that level. Still, in my own little world I show up enough to understand the process pretty well, and I understand this most: my audience is me, I’m the first and most important editor, and only when I’m pleased does the work move along. I’m the primary reader, no one else. If someone finds something in what I do worthy of passing along to her or his readers, that’s tremendous, but if I’m not happy with the prose style, I probably won’t send it out; and if I am, I probably won’t change it for someone else I don’t even know. I write this stuff for me, not you. I just hope you like it anyway.

I exaggerate, a little. Yes, I read the comments editors make and every once in a while one of those comments hangs on long enough for me to consider it. And editors, too, change their minds. I met one at a conference once who rejected a piece of mine and subsequently read it in another journal and told me he regretted passing on it—on the new reading, he saw what I was doing and really enjoyed it.

I like to think all rejection is this way: that somewhere someone who rejected me socially is thinking, “Damn, I screwed up,” sad because I’m being edited by someone else now. It’s a crazy world of rejections and self-doubt. I’ve sent out more stories in one week than resumes I ever sent out in my life. I’ve not gotten jobs I wanted, but I’ve also fallen backwards into the best opportunities in my life. Writing is like that too. Some rejections force us into a new direction, and often that new direction has more meaning and purpose than the original goal. I once wrote a piece in about fifteen minutes, thought it was pretty good and planned to send it to a local paper which has published my editorials before. But I couldn’t find the email address, so on a whim I shot it off to the Washington Post. By the time I returned from the bathroom, the Post had accepted it. Lightning strike. On the other hand, one of my favorite pieces I wrote many years ago and sent out dozens of times still has not found a home. I guess that one’s for me.

One more thing: There’s only one thing worse than rejection and that’s completely ignoring the work or the writer. This is true in the submission world and the reading and book signing world. If you see us sitting at a table of our books, don’t walk past because you don’t plan on buying a book. Come say hi—we’re an intensely lonely bunch of people. And besides, someone else might come over if you’re standing there and that person won’t feel pressured since I’ll be talking to you.

Listen, in the end writers write because somewhere deep inside is a deeply-seeded need to scream, “Holy Crap! Did you SEE that??!!” from some rooftop after an amazing sunset or an incredible connection with someone new, but we don’t want to get arrested. Banned, yes. But not arrested.

It’s that time again. When I was born Dwight Eisenhauer was president and Richard Nixon was his vice. The average household income was just over $5000 a year, the average house just about twice that and the average new care just about half.

I appear on the scene just hours after the first fifty-star flag had been revealed noting Hawaii, and a week before the Pulitzer Prize winning Harper Lee book To Kill a Mockingbird is published.

Benin, Niger, Ivory Coast, Ghana, all gain independence, and Aretha Franklin makes her first recording. Cyprus, the Central African Republic, and Chad gain independence. And in August, the Beatles with Pete Best perform for the first time with their new moniker in Hamburg.

Belka and Strelka board Sputnik with forty mice, two rats, and a rabbit and actually make it back to earth alive.

Hurricane Donna rips up the east coast and in my home state of New York, Governor Nelson Rockefeller declares September 19th Grandma Moses Day in honor of her 100th birthday. She was born at the start of the Civil War and died when I was a toddler. Time is deceptively swift.

I’m amazed by the people I shared this space with. First and foremost, birthdays remind us in fine mathematical style that we are alive and are still part of the population which constantly expands like bottle rockets in the deep blue sky. It bends my small mind to think of this reality that I’m certain everyone knows but few contemplate: I shared this planet with every other human who ever breathed the air. Read Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” as a brilliant reference.

Just in my lifetime: Mother Theresa. Malcolm X. Neil Armstrong. Jimi Hendrix. Pope Paul the Sixth. Lech Walesa. St. John Paul the Second. Thomas Merton. President General Eisenhower. Elvis. Pablo Picasso. Albert Schweitzer.

Rwandan Tutsis. The Lost Boys of Sudan. Steven Biko. Pol Pot.

I shared time with these people; these saints and sinners brushed my sleeve simply by sharing the earth during my stay. I have a loose connection to miracles and massacres.

This world has some serious issues; always has. It is at best, though, a hotel, and every once in a while I take a look at the register to remind myself who else stayed here. Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Mohammed, Ivan the Terrible, Ghengas Khan, all guests just over the slope of the horizon, just beyond some small slice of linear time. On the same human trajectory as mine but before is Geronimo, Moses, Jesus, think about the gentle bend of time, the careen of place that separates me from the disciples, the Visigoths, the founding fathers. All here but just before.

Closer to now, when I look inside the lines of my coming and going, I can see the souls who at one time or another shared with me this spinning blue wad. Not short of miraculous, we claim the same particles of stardust, and that’s what keeps me looking around when I walk down some city street; I want to know who on earth is with me on earth.

Time has ripped past. I was born a month ago. I waded through foreign rivers last month. My son was born last Tuesday. Fleeting. Swift. Impatient. And my thin life falls on the same graph as Richard Wright and Ernest Hemingway.

Carl Jung lectured during my youth, and Ty Cobb watched the same Mets players as me. When I was still cutting new teeth and outgrowing my Keds, I could have headed downtown with my Dad and possibly been on the same train as William Faulkner, ee cummings or Marilyn Monroe. I might have passed them on the street, maybe stood in line at some drug store counter with my mom and behind us because of the blending of circumstance might have been Sylvia Plath or Sam Cooke; Nat King Cole; Otis Redding. We have overlapping lives. On a Venn graph, we share the shaded space.

Judy Garland and I watched the New York Jets in Super Bowl Three. When I was born World War One vets weren’t yet senior citizens and World War Two Vets were in their thirties. Vietnam isn’t history to me; it is my childhood, my early teens. The fall of Saigon was announced over the loud speakers at my high school.

There are empty fields save monuments and markers where soldiers died defending this land against the British, against ourselves, and they stood where I stand and watched the hazy sun rise. Same sun; same beach, same blessed Commonwealth. Don’t mistake history for “back then.” Those people just happened to check out before us. It could have been us. It is us now, watching the orange moon like we do, noticing the calm river, sharing time with loved ones, thinking about others. Getting ready to die since it won’t be long before our lives overlap with the crying call of a newborn Einstein. Did you see that boy running at the park? That girl climbing the tree at her home? Did I just pass by some senator, some Cicero or Socrates, some St Augustine?

Like a couple today buying the same house that young lovers lived in centuries ago, like sour-dough starter. Like a relay race.

My adult son is trying to get a shot of fireworks in front of the moon, but the angle is wrong. When he was just five months old I held him with my hand over his ear, the other ear against my chest, as we watched fireworks out over the Atlantic in Virginia Beach. That was last Friday or so.

What a life. How many times do we reinvent ourselves? How often do we stop in our tracks, get out of the rush and inertia of humanity pushing from behind, and let it all go by, catch the moon over the Chesapeake? Why do we so rarely rest easy in the love of those near and of those still far away when our stay in this world in our time is brief at best.

I love getting older, knowing more people, turning the pages. I miss my mom and dad, I miss Dave and Fr. Dan, and I miss Letty. My parents lived longer than I thought and the others I really didn’t think would check out as soon as they did. Thank Buddha for Ghosts and reincarnation. Just in case I watch the birds on my porch.

Listen, please: