A million years ago I flipped baseball cards with friends on the sidewalk outside our home in Massapequa Park. I’d sit on the cement in my dungarees and Wildcats little league t-shirt with a stack of Topps cards in my left hand, ready with one in my right hand between thumb and index finger, hoping to take the stack on the ground between us. The older cards were limp and ripped in places, but the new ones were stiff, still dusty from the hard stick of gum that came with them.

I’d turn over a rookie Tom Seaver or a Cleon Jones, not knowing then that I held several thousand dollars in my left hand, and since at some point the following year I had the entire 1969 New York Mets squad, at some point I held tens of thousands of dollars. I only knew I wanted to kick some baseball card-flipping butt before I had to head back inside for dinner. We were about to move further out on the Island, to a new house out near the Great South Bay, and who knew when I’d have another chance to do this.

Life was about flipping cards. Ask anyone who was nine back then—they’ll back me up on this.

Everything was easy. For me, anyway. On the other side of the planet the Vietnam War was in full swing, my uncle on his way over, a friend’s brother on the next street was not coming back. And just upstate, music fans would gather in a month at Max Yeager’s farm, while just fifty miles away in the city, the Mets were in last place for the last time, heading in a matter of months to a miraculous championship. Hippies walked down Main Street, the Beatles were together and going strong, Nixon was reelected, and Steve Bezos just turned five.

Just about the time I lost the Seaver card, somewhere above us Apollo Ten was orbiting the moon, doing surveillance for their successors, Apollo Eleven, a few months later. Funny, now it occurs to me that up until that point I lived in a world where we still had never walked on the moon. I wonder what we compared tasks to before we could say, “We can land a man on the moon, but we can’t…”

In any case, I followed the Apollo mission, didn’t care about Tricky Dick, preferred the Birds to the Beatles , and baseball was the universe. I was eight, for God’s sake. My voice hadn’t yet changed.

Yeah, seriously; a million years ago.

That was back when my friends had no last names. They were simply Charlie and David and Chris and Tommy, and Kathleen, the Little Read Haired Girl Kathleen. We had a pool and block parties and barbeques, and sometimes there were blackouts and everyone came out into the twilight evening, my friends and I chasing each other, the adults standing around in the cooling summer air, talking about how, “Over in Amityville they still have lights, and a few houses on Euclid, but they’re out down on Park Lane, and all the way down East Lake.”

Lights. No Lights. Whatever. I was eight.

My cousins lived too far away to ever think about visiting on a whim—a good thirty or forty miles, and the ice cream man would come, and the television was a big black and white console on which my sister would watch Gunsmoke and Bonanza and my brother would watch Star Trek and the Olympics from Mexico City and I’d watch cartoons or Andy Griffith. And I’d watch baseball when it wasn’t blacked out to local viewers because the game over in Shea Stadium hadn’t sold out.

And at night after the Late Shows ended, if I was still awake in bed and one of my parents had fallen asleep on the couch, I could hear a man’s voice declare, “That is the end of our broadcast day,” and the screen would get fuzzy with a low buzzing noise all night. Didn’t matter which of the five available channels was on, they went off the air.

The friends I have now were from all over the place back then. Rick was probably about to leave high school and hitchhike across the country, Tim was playing high school football in Philadelphia; the other Tim was a lieutenant humping his way through the marshes of Vietnam, and Sean was learning from his father upstate the value of giving, of volunteering. And when I think of my friends back then, well, who knows where they are now? I think about them when I pass through Kennedy Airport or the rare times I’m on the Island and stop in a store, wondering if I just walked by or stood in line behind someone that at one time a million years ago was my absolute best friend; the one I’d know forever. It was so easy then. When you’re eight you’re simply always going to be eight—no discussion. Your parents will always be there, your siblings will always wake up early with you on Christmas morning to exchange gifts before you head down to the living room to see what is under the tree, and baseball card-flipping is more important than school.

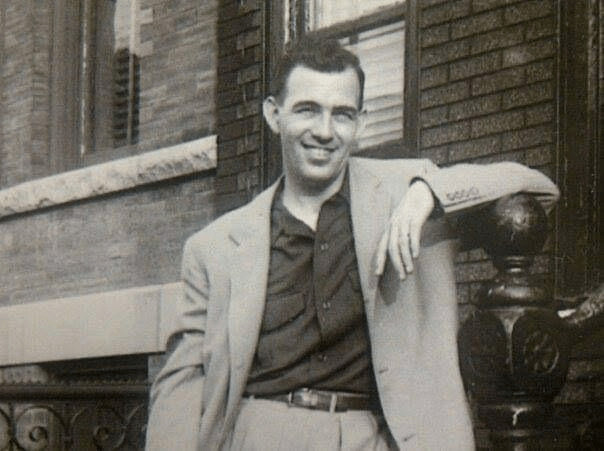

Sometimes I have to try hard to make myself realize that that eight-year-old was me. That it wasn’t some kid I saw in a movie or read about, or a child someone told me about. That was me, legs crossed on the cracked cement sidewalk on East Lake Avenue, the same me that sits now near the river and listens to the approaching flock of geese, watches the descending sun, feels the faint brush of something familiar, like a song I once knew or a memory of someone that was kind to me. The same me that barreled across Siberia with my own son, who is now more than twenty years older than I was back then.

I’m at the other end of this game now. It’s late, and I’m tired. I have some writing to finish for readings next week, and a few deadlines looming, and I walked out on the porch and listened to the cold night, the clear, star-filled night, mid-winter night that is colder than it should be here on the bay. A friend of mine believes in reincarnation, believes we come back as, well, some other living form, whether another human like the Dalai Lama does, or as an orangutan, but as something. I’d be okay with reincarnation, but I want to come back as me. I want to do this again, make those mistakes again, fall in love again, have my heart broken by the same girl again, play golf with my father and brother, receive care packages from my sister when I was at school, move into those dorms again, play tennis again. Hurt and give and cry again.

If we agree eighty years is about a life, anything more than that is a bonus—overtime, if you will, then I’m now entering the fourth quarter. Games have been won or lost in the fourth quarter. Some of the greatest plays in history were made in this part of the game.

Back in 1969, the Mets turned a losing season into a winning streak now universally called miraculous more than halfway through the season. But as Mets catcher Jerry Grote pointed out, “It’s not a miracle, it is persistence, it is determination, it is faith in yourself and each other.”

It’s not over yet. And it just might be that the best resource I have so I can face whatever comes next on this pilgrimage is that eight year old boy somewhere inside who could flip baseball cards with the best of them.