One:

Two:

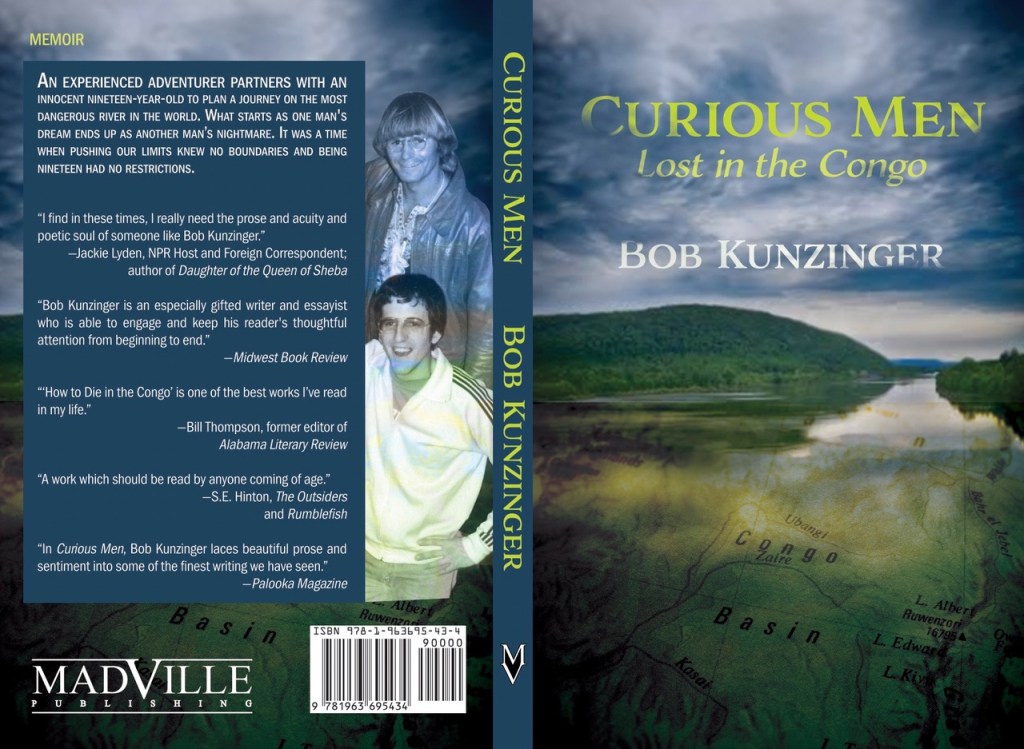

CLICK ON THE BOOK COVER BELOW TO ORDER:

Memory is as fluid as anything in our lives. What happened and what “seemed to happen,” as writer Tim O’Brien points out, can often be confused. When looking back we might have a habit to recall what seemed to happen, reality having been washed and hung out to dry over the course of decades. Sometimes though we can recall nearly ever nuance of a time in our lives for its significance, its uniqueness, or its romance. I have a pretty sharp memory when it comes to many events. A friend of mine and I were talking not long ago about how we can both remember nearly every detail, everything, about a period in our lives so long ago you’d think it was from another life. Many of us have times like those which, for whatever psychological reason, we can summon up to the point of remembering the clothes we wore on a particular day.

My basic memory for most things is pretty solid. I remember all my phone numbers and license plates, and, worse, the phone numbers and license plates of friends of mine. The old joke about song lyrics holds true with me, but so do the times spent with extended family. One of my only memories of my paternal grandfather was him weeding a lot he owned next door to his house on Long Island. He died when I was five, so I was no older than that, probably still four. But I picture that day, those moments, perfectly.

Some years ago when Meanwhile in Leningrad came out, someone asked how I can remember the conversations I had with survivors of the Siege of Leningrad, who at the time I knew them were in their eighties, and I wrote the book several years after our conversations. I said, well, first of all, they’re never going to find or read the book, so there’s that. But more accurately, when a woman sitting on a bench holding my hand tells me about dragging her dead husband and son across the city to leave in a mass grave, and she sat with me clinging to their photograph sixty years later, I will not forget any of it. Much of the writing in that book falls in that category. Did the conversation happen verbatim? Doubtful, but the gist of it is pretty damn accurate. There’s an old journalism method that when you write the piece and include quotes from someone, call them up and read what you wrote to them and ask, “That’s pretty much what happened, right?” Nearly all the time they’ll say yes. Can you remember the words, exactly the words, you spoke an hour ago? Exactly. If that’s not possible as in this case, I rely on memory and notes.

Memory is reliable or not depending upon just how present we are during the event. That time so long ago when we said we could remember everything: We were both very much present at the time, we lived the example of what would later be called “mindfulness.” Of course we remember. Likewise there are times I so shut out of my memory it’s like they never happened at all.

Still, some events are so close to my soul I would need the team from Matrix to come extract them.

Like what happened in 1980 and 81, when I was a freshman and sophomore in college, the subject of my forthcoming book, Curious Men, from Madville Press. Of that time then, I remember everything. I watched, studied, and listened so intently that this memoir could be considered a documentary for how clear the details remain to me four and a half decades later.

I like that “memoir” includes the Spanish word “oir,” to hear, because much of memory stems from what we hear, and as a nonfiction writer I am bound by listening to the world around me, sometimes to the one sitting in front of me, and those sounds of vowels and consonants and the musicality of language I know will never escape my recollection.

My friend, colleague, and former officemate, Tom Williams, once introduced me at a reading as a non-fiction writer by saying, “Here’s some shit that happened to Bob and the best he can remember of it.” That’s pretty spot on. Despite a degree in journalism, I never had what it took to do the job in the traditional sense like so many I graduated with, some of whom have won prestigious awards for their work. I was definitively not up to that task. But I could handle the feature work, the “Let me tell you what just happened to me” work, just fine. In college, my friend Deb used to help me with news stories and I’d help her with features. We knew our strengths. I had a column in the college paper for which I ventured out into the community and did something, and then I wrote about it. I went horseback riding in Machias, New York, flew planes in Wellsville, kayaked the lake in Allegheny State Park, and sat on the ground behind campus at Merton’s Heart. Those events I could remember. I knew how to be present. Most of those activities were out of my wheelhouse at the time, so recalling what happened was easier. I was paying closer attention, sometimes just so I wouldn’t die.

Memoir is like that. If we can’t remember it we’re certainly not going to write about it.

But not this time, not this book. Summation: As a college freshman uninterested in the normal activities of my floormates–that is, drinking and drinking–I felt lost and disconnected from everyone. Then a family friend returned from the Peace Corps and asked me to help him plan a trip, solo, on the Congo River. So I did.

Long story short, it didn’t work out and his trip became mine. The first half of the book takes place in western New York. The second half in the Congo.

Still, that’s not what the books about.

Most of it takes place now, in every classroom across America where nineteen-year-olds sit and try and find something worth doing, something that reaches deep inside them and wakes them up. I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty-six years and one thing hasn’t changed: they’re scared out of their minds. They’re alone in a new place far from home living in a room this size of their car with a total stranger, and every adult within earshot constantly wants to know their plans for their major, their careers, their lives. It is often unbearable.

I was exactly like that back then. Until a friend walked into my life and said, “I have an idea. I need your help.”

We were so young.

So that’s what this memoir is about: About that time back then. What we did and how and why we did it, yes, but mostly about being nineteen and far from home looking for a reason to exist at all.

This is how I remember it.

Coming this winter:

This one’s for me.

When I was out west we hiked uphill (because the West is uphill) to a waterfall. I’m not sure of the elevation but it really doesn’t matter since I live at sea level and the waterfall is not. My home is about 80 feet above sea level and a short stroll down the hill is zero.

A few days before the waterfalls we were at just above eleven thousand feet; June, and still there was snowpack on some of the trails. At night we had a fire going, of course to toast peeps but also to keep us warm. In the cabin we kept the wood burning stove going all night. Back home the ac was running strong. Back at zero elevation. that is.

On the way to the waterfall–it was hot that day–I had to stop more than a few times due to my unconditioned lungs. I had no issue with my heart or legs; no, I felt pretty strong actually. It was just the lungs which in my mind looked like the deflated oxygen masks in planes. I wanted to quit; it was clear I wanted to quit, but it was also clear I just needed to catch my breath and push on. “It’s just a little further” translated to me to those days driving my son long distances and from the back seat I’d hear an impatient, “How much longer, Daddy?” “Not far,” I’d say, as if a two year old could translate “not far” into some sort of calculable distance. Yeah, that was me on the mountain as kids–I’m not kidding, kids!–ran past. I reminded myself they’re closer to the ground and need less air, and “it’s just a little further” to me translated to “move your ass for Buddha’s sake, or we’re going to have to make camp soon.”

I made it. I sat on some rocks and watched the majestic water fall from other rocks, down to a pool, off into a creek, down the mountain past the path we just hiked. I quickly gained my energy back as the issue was my lungs inability to climb at that altitude, not “be” at that altitude. A few days earlier we were at eleven thousand feet and I was fine because there was little steepness about us; it was a casual altitude gain. Plus it was colder. But there I sat outside Ogden, Utah, having climbed what I swear was the Matterhorn and I watched the sky grow bluer, watched the water mist up into the trees, and watched the world below try and make excuses for itself. I can’t recall ever feeling so at peace.

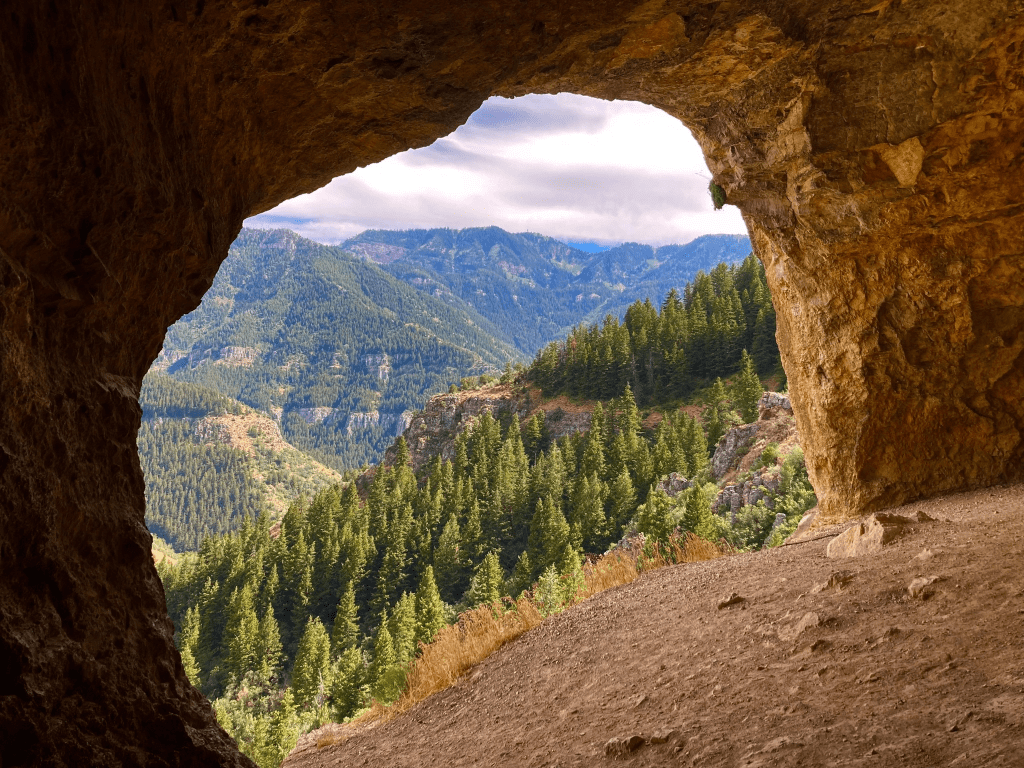

A few years ago we did the same thing not far from there to a place called “Wind Cave” and that was more than just a steep climb, for a flat-earther like myself it was like scaling The Freedom Tower, but we climbed and a few times I wanted to quit–apparently I’m not adept at steepness yet–but I didn’t, and when we came around the top slope and walked back down to the opening of the wind cave, there was nowhere on earth I would have rather been. And so again in the mountains, and then again at the waterfalls.

Fast forward, for that is the theme here: Today I wondered about two distinct things: Why is it so hard for me to do these things when I used to have no issue with them when I was younger? and why did I push myself to finish when I could have so easily stopped without objection?

Let’s get the age bullshit out of the way first. Yes, there are conditions which can slow a person down as we age, and it makes it harder to do what we could do with ease decades earlier, but all things being equal, one can battle a decreased metabolism by eating right and working harder. The list of reasons those antiquated excuses are irrelevant aside, internal motivation has more to do with accomplishment than external excuses. I have some experience in fitness and working with people whose challenges could not be calculated, but who, with the right motivation and persistence, reached their goals. So why is it so hard for us other than absolute and flat out indifference as our minds are occupied by other issues? And two, what changed? Why did I push on despite my better judgement only to find out I was capable of more than I thought? The company? Partly. The kids running past? No. The beauty at the end of the hike? I promise that wasn’t on my mind while dry-heaving into the creek.

No, something different took over.

I wanted to do it for myself.

***

I went to the Y today, again. I’ve been going on and off for some years now, though I took a break during Covid and another break not during Covid. I get bored, or I find something else to do, or…or…or…I lose some weight and I get in shape then I tumble back. This is normal. While my old boss at the fitness club could take an eighty year old and make them feel young and able to accomplish anything–and they often did–it was more normal for a healthy, capable young-something to cave at the first sight of a donut. Enter me.

But I have gained less time, and that is something they and most of the members I trained when I was there did not have at that age back then. It takes a while to understand that all we gain as we age is less time.

Tick tock tick tock tick tock people; times ticking away.

When I did the math this past weekend as the calendar turned on me again, I realized the list of things I plan to do is longer than the remaining time allotted, and that’s if I’m generous with myself. So I went to the Y today just like any other day, but this time I wondered if I could push it a bit, so I increased the incline on the treadmill and turned up the mphs. And again, until my heartrate was safely beyond what I normally do, until I was sweating, which I rarely do, and until I was at the point I never have been to before at the Y–the point where I wanted to quit for a reason other than boredom, so I pushed the dial up a bit more and for ninety minutes I climbed to the wind caves and to the waterfalls, I climbed Mt Wachusett in Massachusetts and to the upper falls of Sabino Canyon near Tucson. It brought me back to those days, first, when I taught classes at the club and I had to push myself because the class wanted to be pushed, and then earlier when playing tennis, and I wasn’t done until I dropped on the court, spent.

Why? Because I want to ride my bike to Coos Bay, Oregon, and I want to go to Seattle and hike Mt. Rainer with my cousin, and I want to make the climb to the waterfall a stroll, a meander. Because I saw the clock. I didn’t want to look; I really didn’t, but I did and I saw it as the large digital numbers clicked over, and I did the math because I’m pretty good at math and the distance from here to 80 is barely enough time to love anymore, barely enough time to dream anymore.

Something was different today. Something clicked. It’s that there are going to be a plethora of things out of my control as I move forward, so I’m going to take control over those aspects of my life I do have some say about. Of course I’m not going to get back to my club weight again, which is fine since I forgot to eat from 1983 to about 1988, but I am going to get to the point I believe I can if I decide to. And that might be all I need during this last push to the summit.

And by the way, we do these things at this point in life for ourselves, no one else, and that’s different too.

This time it’s for me.

I had an unconventional youth. Specifically, I did not lead the normal life of a nineteen-year-old away at college. While my floormates were drinking heavily and sleeping until noon, I was at classes early to get them out of the way so I could head out to the Allegany River, or up to Niagara, or out to Chautauqua Lake, canoeing, listening to fascinating stories from a friend of mine, helping him plan his return to the Congo River for an adventure I couldn’t possibly contemplate prior to then.

I have two books coming out next year. The first, Office Hours, is a “Sedaris-like story-telling” of thirty-five years of college teaching. The second, Curious Men, is about that time back then in college myself, planning the Congo trip, turning a first semester probation they said was due to grades but I knew was due to complete indifference, into an honor-roll semester due to my sudden acute interest in absolutely everything. A friend of mine used to ask, “You mean that year you were on crack without ever touching a single drug?”

Yes, that year. Nineteen.

Memoir writing is a challenge for the need to engulf yourself in the emotions of a time that was apparently significant enough to warrant a book, yet absent enough of those same emotions so the reader can find the bigger picture of the narrative, the part that must reach up and out of itself into their lives, show them their emotions instead of displaying my own.

I brought this up because I just finished it, the book, Curious Men: Lost in the Congo. As a point of reference, though, and in full disclosure, I started it forty years ago. I’m a slow writer.

But the primary question publishers, publicists, agents, and–what do you call them? Oh yeah, readers–ask is, “What’s it about?”

So that needs to be split into two answers. Most people mean “What happens” when they ask what it is about. And that’s fine and not too difficult to answer: A friend asked me to help him plan a canoe trip—solo—on the Congo River. I did, and he went, and he never returned. Eventually, I went. But I returned—most of me anyway. This might be of interest to readers, particularly those who have enjoyed my writing in the past, or those who like adventure, distant places, rivers. Mysteries, even. Possibly psychology. But that “what happens’ response makes it all seem very 1981ish, and little more.

Which means there must be a second answer for this to work. And that is the true response to “What’s it about?”

In this case, it’s about being nineteen-years-old. It’s about being on my own for the first time, out from under the parental umbrella only to be thrust into a world where countless adults want to know my plans for the rest of my life, my major, my summer internship possibilities, my “declaring” of a focus for my entire career before I’d even taken a single class, all the while living with someone I’d never met on a floor with ninety guys I’d never met who seemed to insist I drink despite my desire not necessarily to not drink, but not to drink because they insisted; and all of us with two bathrooms, one payphone, and honestly little guidance to navigate. This wasn’t the military where some sergeant told us what to do when to do it how to do it but never why. We were paddling out in the deep-end, completely solo. Hence, the drinking and the need to join the pack. Just because I didn’t end up face down in the stairwell every night doesn’t mean I didn’t understand the draw of the need to do so. It’s just that I found my own alcohol of sorts.

I found another outlet, something well outside the box, and in doing so ended up with a working knowledge of a few African languages, an understanding of the fauna of equatorial Africa, a comprehension of diseases, some knowledge on how to temper loneliness, and a taste of a particular lesson I couldn’t find in my mass comm classes: outrageous adventure is simply a matter of deciding to do something and following through. I discovered that I didn’t need to follow some template to be alive. I learned that maybe it was everyone else who didn’t fit in. At least that’s what I told myself at the time as a defense mechanism.

But something changed over the years. You see, I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty-five years now and that alters the narrative some.

In the end, Curious Men is not about Africa, it’s not about the Congo or anyone in particular; it is about being nineteen and scared, and how that has changed in the decades since I ate sun-dried fish while bantering in Lingala, and most importantly, learning how to jump, knowing, absolutely understanding, that once you jump, you’ll either land on your feet or you’ll learn how to fly. Unless you don’t. Then you need the “What’s it about?” to step to the plate. Sure, it takes place in rural western New York and ruraler central Africa, but the narrative and the theme often divert.

Indeed, I’ve been staring at nineteen-year-olds for thirty five years now, and students today are no less timid then then, no less adventurous, no less interested. The difference is they are infinitely more distracted, bending toward convenience and accessibility, seeking and finding adventure on a screen, through gaming and TikTok, and I don’t doubt that if I were nineteen today the rivers I sought out would be virtual from the safety of some Virginia Beach bedroom. Maybe I was born at the right time, back when you sat around some diner eating wings and talking until some spark ignited, and you drew maps and made lists on the back of placemats, and then, most importantly, you followed through.

Curious Men: Lost in the Congo, is, as S.E. Hinton (The Outsiders) wrote, “A story that should be a must read for all teenagers—and adults alike for that matter.”

I’m just deciding now on the dedication. That’s a tough one. In ten books I’ve ever only dedicated one; The Iron Scar: A Father and Son in Siberia is dedicated to my father and my son. I’m not sure yet I am going to do so this time, but I’m leaning toward this, a variation of sorts of something Richard Bach once wrote:

To the nineteen-year-old who lives within us all

The piece I wrote which was the fastest to go from concept to completion, in ready to be published form, was in 2016 about Arlington National Cemetery. From the time I sat down to write to the moment I sent the version that would eventually be published in the Washington Post spanned just twenty minutes. We call that a lightning strike.

The slowest has been “in progress” for more than forty years, but as of a few days ago it headed to the fast lane and dragged my procrastinating ass with it. Here’s what happened:

When I was a freshmen and sophomore in college, I was deeply involved in the planning and training for a great adventure of a friend of mine who had graduated from the college about four years earlier. While it was not my adventure we planned but his, in just a couple of years it unsuspectingly became mine, and I have tried to write about it ever since. A few pieces have been published by journals such as Matador Review and Palooka, and the entire 275-page manuscript became my MFA thesis, Fly. It was more than a little weak, however, and I subsequently attacked it with a pen, markers, highlighters, and anything else to move hard-copy paragraphs from chapter to chapter and front to back. I trimmed it down to a not-so-well written 50 pages. That version, Curious Men, received some decent reviews, but the primary response involved readers wanting to know more. That can be both good and bad, and in this case, way bad. I was never satisfied with the work; I could not capture the excitement—exhilaration really—and anticipation at just twenty-years old, followed by confusion and disappointment. For me it became the quintessential “you had to be there” narrative. The true story goes to emotional extremes, pulling this nineteen-year-old boy out of some catatonic state and into some woke existence of adventure and exploration. The written version, well, didn’t.

Long story short: the long version was way too long, and the short version left people longing for more, indicating I came up short. I can’t get it right.

Honestly, I have been thinking about, writing about, messing with, focused on, and ignoring this story for forty years. I long ago decided that I would never get it right, figuring it would be wrong to put it out there. I have letters, maps, notes, journals, emails, and a half dozen different versions of the same manuscript all saying the same thing, and not very well.

Until last month. On a drive to Florida I listened to the audio version of Beryl Markham’s West with the Night. I enjoyed this version of the book I had read several times decades ago, but somewhere while driving past the dilapidated and very incorrect theme park, “South of the Border,” in South Carolina, my mind drifted back to my manuscripts. And on I-95 South I figured out exactly how to start, what to focus on, and I finally understood the problem I’ve had all along with the narrative: It isn’t about anyone else’s journey, it’s about mine. The book is not about the character I had been writing about for forty years; it is about me; I’m the protagonist.

When I got home, I pulled out the long, bound version that was my MFA thesis, as well as the short version in a binder on the shelves behind me. I pulled up the published versions which focused on one segment of the story, and I reread the longer version, Curious Men, and sat back knowing two essential things: First, they all suck. Second, I know now exactly what I need to do to unsuck them. My energy has returned, some internal motivation has been reignited.

It was a four-hour session that first morning I did little more than read through pages and chapters with a fine-tooth comb much like the NY Times editor must have when he first received the Pentagon Papers. What I believed was a story no one would care about and which I was not telling well at all, I finally knew exactly how to tell so others would be interested.

It was both exhilarating and terrorizing. I am ready to get back to this and get it done right this time, yet doing so means not only facing the possibility of not getting it right yet again but also dealing with some realities I’d almost rather let lie dormant.

But if my trip to Florida followed by an inspiring trip to western New York ignited some spark, it would be just a few hours later that some bomb exploded in a manner that sent those proverbial chills up my spine.

Long story not so short:

I received a message that very afternoon; I mean I closed the manuscript, got in the car to get a Slurpee, was sitting in the parking lot thinking about the protagonist of the work, me, and I received a message from the sister of the subject of my book. Be clear: I had never heard from her before in my life; I did not know she existed. Yet, she messaged me the very afternoon I had started work in earnest on a book about her brother.

She said in part, “My name is Kim and I just read online one of the stories you wrote about my older brother. I never knew him, he left with you that last time when I was five, and I am now almost fifty. I saw online you are a writer now and I am wondering if you plan to write a book about him.”

Again, that message came just hours after I decided in earnest to get back to it, my desk covered with pages and maps and journals and emails. Insert Twilight Zone music.

Kim wrote that she remembers the leather coat in a picture of him with me and a friend, Annemarie. We’re in a hallway at the college, laughing. She remembers him dropping her off at kindergarten the last week she saw him, and her teacher asked if the man in the car was someone else he happened to look like. She still has an old, worn sweatshirt of his he left behind. I asked what made her write me that day and she said their oldest brother George had recently died and it got her thinking about her other brother who was long gone, and so she found me online and messaged me.

I told her about my day up until then, and she agreed it was more than a little freaky that she chose to write me that day. Strange, but when I read her message, I didn’t picture a fifty-year-old, but instead a little girl.

The most difficult part of writing is getting started. In this case, I started more than a few times, and each complete version begins differently. Chronologically, the story starts in Virginia Beach in the mid-seventies. For narrative sake, it starts in February 1980 in my small dorm room. If I want to put a “hook” at the front, it starts a few years later seven thousand miles southeast of here in a then-peaceful, not-so-small-anymore village in what is now one of the most volatile and dangerous places on the planet. In a few versions it starts with a nightmare I had three or four times—same one—that woke me up. In one version it starts at the end and works its way backward.

None of them worked.

But when I think of that time, that experience; when I recall the “me” of back then and the life that I had, the energy and motivation and confidence I had then; when I think of the times I’ve told this story to others, my thoughts always go directly and immediately to one place: Antonio’s Italian Restaurant on Route 417 in Allegany, New York.

Last week I was in western New York, and I walked along the Allegheny River, followed a path through the woods, and remembered my life in that very spot almost forty-five years ago. I felt younger and vibrant yet somehow tired and disillusioned. The perfect combination for a work of creative non-fiction.

So that is where it starts. Time to wake this narrative back up so I can put it to bed and send Kim her own copy of a book about her brother that in the end isn’t about her brother at all. It truly should not take forty years to finish writing a book. On the other hand, some books, perhaps, should not be written at all, and that may well be the case here.

I have learned that sometimes it is best to not search too long and too deep for a resolution to the narrative, and that in real life sequels are rare. But I’m a naturally curious person, and it seems to me now that Joseph Conrad was absolutely correct: “Curious men go prying into all sorts of places where they have no business.”