No running water, no electricity, no means of communication. We hiked from our cabin at just over ten thousand feet in the Uinta Mountains to just over eleven thousand feet. Snowpack remained, and while the temperature was pleasant, often even warm, a quick turn into the shade marked the cool dryness. In the evening we kept a fire going in front of the cabin, cooked on a camp stove, drank, went for a walk to watch the moon rise—which didn’t—walked to the dock at Spirit Lake and lay on our backs to watch the abundance of stars. An otter or two swam by, a few moose showed up in the field, chipmunks buzzed about, and the unmistakable peace of absolute silence dominated the days to the point I didn’t even notice. The nights turned cold and we fed the small, nearly 100-year-old cabin’s wood burning stove long enough to make it to morning.

Absent was the news, cellphone reception, communication with anyone else save the lodge owner and his wife, no neighbors in the few other working cabins to chat with, just the indescribable silence and laughter, a lot of laughing.

I worried about grizzlies. “There are no grizzlies here; they’re over in Colorado. Just black or brown bears.” So I worried about black and brown bears.

I worried about snakes. “There are no snakes at this altitude. Too cold.”

Damnit, I needed something to worry about. Habit. What I didn’t worry about was the disconnection with the world; being above the tangled waves of electronics saturating the air just a few thousand feet below. I could breathe; well, except for the air being so thin that I couldn’t breathe. And I could in that brief stretch of days, for the first time in a long time, be unapologetically myself because I knew I could. Sometimes it takes a friend to reveal who you really are. Sometimes it takes a lifetime.

Bob Unplugged.

I’ve been this way before, a long time ago during my sometimes-weeklong jaunts into Mexico before cellphones, or two excursions into Africa, and other places where I was mostly alone, or where the people I was with were equally absent of some umbilical to all things civilized, and all that was left to do was to talk, so we talked. Indeed. We talked about how we missed our moms, we talked about what breaks our hearts, we talked about what we dream of and what we don’t dream of, we talked, as Harry Chapin described, “of the tiny difference between ending and starting to begin.” We talked about how sometimes it takes years to understand the beauty of silence, the value of peace. Remember talking? Not words out loud, but real talking.

The night before I left Virginia I hit “Send” on the email to my publisher which contains the final draft of a book which talks about, in fact, celebrates, that very sense of disconnect, the abandonment of society, the push into the unknown. Early one morning after wandering to the outhouse and then up to the field to see if the moose had returned, I wandered to the lake and walked out on the dock. A soft orange sky spilled just to the top of the mountains, and the water worked from dark black to its normal greens and blues, and I stood alone before the dawn and my mind dislocated itself from time. This could be 1981, I thought, remembering a solid portion of my just-sent book; or it could be 1984 half a world away. It could be 1986 in Pennsylvania, or a year later waist deep in some equatorial river.

It might be years from now or just as easily the Jurassic or Cretaceous periods when dinosaurs tramped about these very hills. I forgot what day it was, and then I forgot how old I was. And then everything fell apart because that happens, things fall apart, but as it turns out that just makes it easier to rebuild from scratch.

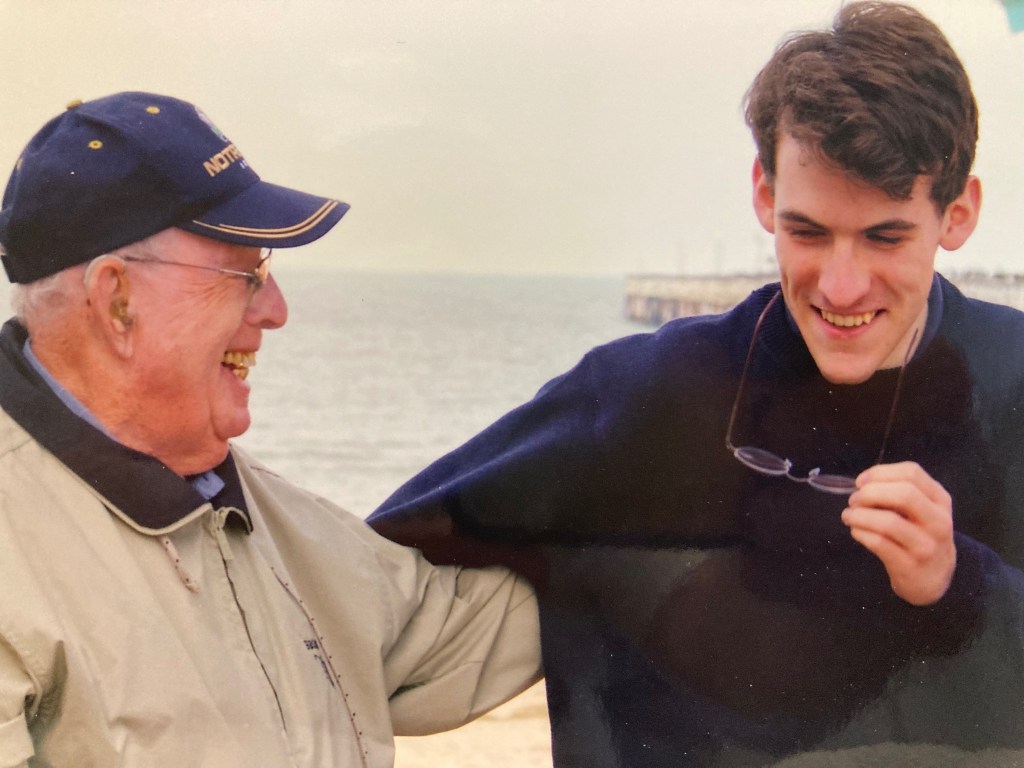

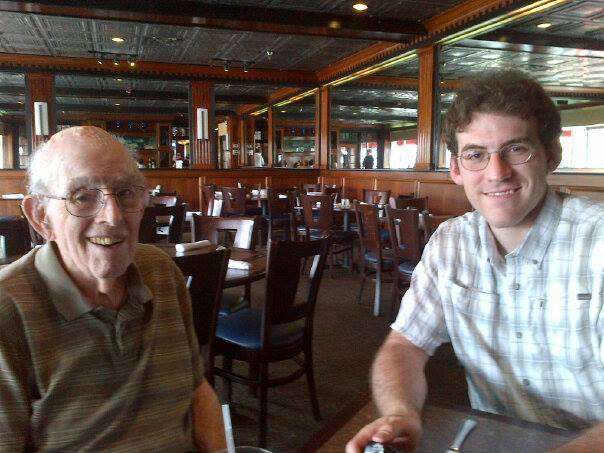

I found myself on the dock completely at peace no longer worried about anything. I lay again on the dock as we had the previous night but this time alone and looked up and felt transported in such realistic ways that to describe it here would be to hack my way through this short reflection, but I was transported not to Pennsylvania 1986, not to Senegal or Allegany or the Congo. My entire presence slipped into Great River, New York, nearly fifty years earlier to the very day, and Eddie Radtke must have been somewhere in the woods looking for firewood, and I stared past what must have been the Great South Bay early one morning which he and I had explored daily for a solid wave of our childhood. That’s where my mind went; it reeled northeast about as far as one can, and slipped into 1975.

It was like being back in 1975 at the start of something but this time knowing how to handle it, knowing what to say right and what not to say at all, this time. I had not yet unearthed tennis courts and guitar shops, not yet swallowed the ocean water of the southeast beaches, not yet changed my mind, not yet learned hesitation and self-doubt that befell me just a decade later.

—

I turn sixty-five in two weeks. This year that day is tangled up in so many memories and symbolism, but something is different now than just a few weeks ago, pre-disconnect, if you will.

At one point in the book to be published later this year, I had been working in a bar in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, with no true sense of direction except the absolute conviction that the lack of direction was not working for me. Late one night, early one morning I woke on a bench near a lake in a local State Park with no real recollection as to how I got there. I had not been drinking, no drugs, no overworked exhaustive excuses led me to the familiar shore where I had at one time laughed so hard. No, it was my complete indifference that brought me there. And I sat up and waded into the lake to my waist. When I returned to my home that morning, everything changed; or, better said, I changed everything.

Peace does that. Silence, and the depth of some connection that is difficult to find does that.

I lay on the dock at Spirit Lake and remembered the bench two thousand miles east. I’ve had so many changes this past year, perhaps more than in all my previous years combined, and I thought of Jackson Browne: “Oh God, this is some shape I’m in.” But I recalled not the last twelve months but my long drives into Mexico more than forty years ago when I thought I’d find the answers, or the walk across Spain, or the train across Siberia. All those times I was so at peace, so much in the moment and loving my existence, but I had not been this much at peace with myself and who I am—or, better said, who I need to be—since that morning in the park when I felt some sense of absolute clarity, when on a dime I let everything go, disconnected from absolutely all aspects of thought and commitment and simply let myself be myself as I imagined I was meant to be. And I lay on the dock and thought of Paulo Coelho who wrote, “Maybe it’s about un-becoming everything that isn’t really you, so you can be who you were meant to be in the first place,” and things seemed suddenly obvious.

Thank you clarity.

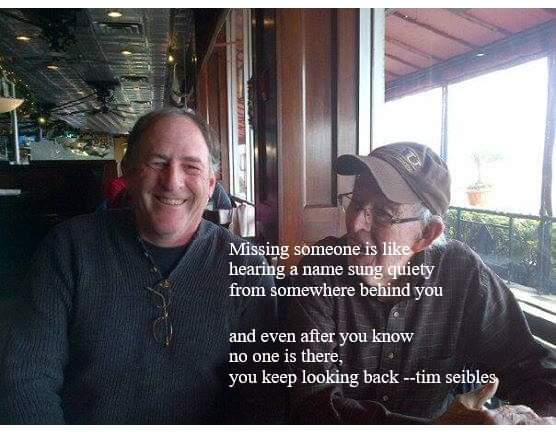

We packed, we meandered our way four days later though the mountains to the lowlands through a small swatch of Wyoming and back into now, back to suburbia, back to the news—the bombing of Iran, the bombing of Israel, the war in Ukraine, the disarray of Washington, the murder of protestors, the abandonment of morality, the sacrifice of truth—all of it, and I briefly envied those who left—Eddie and Letty, Dan and Dave and Mom and Dad. They have been spared this nonsense.

But, briefly, so was I, by choice. We sat in chairs around the fire and laughed like hell when I accidently burned off the soles of my sneakers, laughed harder when after banging my head several times on the exceptionally low doorframe, returned at one point to find the door jam covered in bubble wrap, laughed at the sudden appearance almost on demand of a family of moose, and laughed at the nature of change, the value of friendship. We too often choose not to step away from it all. Seriously, metaphor warning: If you keep your feet too close to the flames something’s going to burn.

I’m stepping away from the nonsense; life is too short. Six and a half decades down and I’ve already outlived nearly everyone I know, so I suppose it’s “time and time and time again to find another way.”