So here’s one I wrote and let it go. It’s partially told in a piece in my short collection Howl at the Moon (Cuty Wren Press). It came to mind this morning because I’m leaving in a few days for Amsterdam, and I’m sure there will be cheese involved.

I was in the Netherlands about twenty years ago, maybe twenty-five. I lectured at the University of Amsterdam and talked about art and Van Gogh and death. Normal stuff. In class one day, which was open to visitors and in which everyone was required to speak English, an older woman whose late husband was an artist sat in for the lecture, and afterwards she gave me an etching her husband did of a local cathedral. When she learned I was going to find a way up to the Zuider-zee, she offered me her son’s motorcycle for the day. Students gathered to talk about Van Gogh and about America and more. While the woman and I spoke, they talked amongst each other. One guy asked another if she was working that night and she said no, but the next night she was. He told her he’d come by. Another said it hurt to speak in English, and the young woman said it’s good for him to learn, that she wants to learn as many languages as she can. They all talked about van Gogh’s art.

That night on my way back to the hotel, I walked through the Red Light district to use a computer at a Brown Café to tell my officemate about how it was going so far. The windows of the district display scantily clad women, select lingerie on the floor, a couch, maby velvet, sensual surroundings and lighting. They move about tenderly like flesh and bone mannequins, and when a prospect passes, they urge him to pause, consider coming in for a quick turn. They whisper to them in Dutch, in English, French, German. There’s a back room for the business end of the exchange. I kept walking.

The next morning was one of those movie-set days with a perfect temperature, ideal soft breeze, postcard tulips and windmills, dikes running roadside holding back calm waters. I rode out to a Volendam café on the docks where som sailor just back from the states finished washing down his ketch, and we talked about his Atlantic crossing, about the Chesapeake Bay where he had been, and about the cheese he had on deck which he shared with me. We went in the café for a beer and the waitress offered some Gouda and bread with eel and herring. She said the cheese was from a small factory just a few miles away and that I should go, so I did.

Inside the cheese factory—a small barn-type building—a young man and woman stirred a vat of vlaskaas cheese which was sharp, and they told a half dozen of us how gouda is made and molded into wheels and how we shouldn’t refrigerate it, and how healthy it really is, being a hard cheese, including aged, smoked, and toasted. I bought two wheels for fresh gouda and stacked them in my pack and walked outside where a few other travelers from a bus sat at a picnic table.

A Dutch girl about twenty-five eating cheese and drinking white wine asked me to sit with her, and when I told her she looked familiar she said she had been at my lecture, and she swept her blond hair behind her ear and that’s how I knew her—she did that the entire reading, it kept falling forward and she kept sweeping it back and I thought Geeze just tie it back already. I told her simply I recognized her.

She offered me a glass of wine and retrieved a plastic cup from inside, and I shared her cheese. Her name was Abby and she came up to get a few wheels for her family and one for her. After about thirty minutes and a glass of white, the bus driver called for them to go so she left and said she’d hoped to see me again, and I walked toward the bike to leave. The cheese was heavy but I was glad to have it, and the perfect day made me not care so much.

That night I packed for my trip home the next day and decided to head back to the Brown Café to write again to my officemate back home to tell him about the ride out to the North Sea and the sailor and the hair-sweeping blond. I did so on the upper level of the first café I came to where the open door swept the smoke from the hash up to the internet café section so that by the end of my email I couldn’t spell anything correctly.

I left the café and strolled around the district where people drank espresso and the aroma of various smoke filled the narrow streets and top-shelf women worked the windows, and if you can see this coming you must believe me that I certainly didn’t see it coming at the time: I turned a corner and glanced at a blond in a prime-site window, and it was her, Abby, the hair girl with the cheese, and she motioned to me like I was just another passerby, but then recognized me and sat up more from where she had been prone on some pillows and her white lingerie lingered just a bit behind, and she pulled her strap back on not trying too hard to do so, and she pressed against the glass and urged me to come inside, motioning toward the door on the left. I thought about just walking by but that thought didn’t hold so I went in just to say hello. She cut me a slice of the cheese she had bought that day and she pointed that out, that it was the same wheel of cheese that we shared earlier, and that thought seemed to connect us closer than I cared, but it hung there between us. I had one slice of the vlaskaas on the table and said I didn’t want her to lose business on account of me, and that I really had no intention of patronizing her profession, and she smiled and said she understood. I left, and on the way out I passed the guy from class who had asked her if she was working that night. He glanced at me and I laughed. This is not like the colleges at home, I thought.

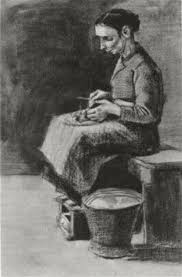

On the way home I walked by the Van Gogh museum one more time. It was quite in that part of town, and I stood in the cool night air, the sweet aroma of flowers everywhere, and remembered Vincent’s words about Sien, a prostitute who lived with him for a while with her young daughter. About her he wrote to his brother, “I believe there is nothing more artistic than to love people.”

Next week I’ll be there, at the museum, at the village where he lived a while with his parents, and along the canals. Just look at how everything in our lives moves on, grows and changes and, eventually dies. We age and hold out hope that some of who we used to be remains, knowing, of course, that is true only for a little while. Since I walked those streets last, friends and loved ones have died and my world has changed time and time again, but this week I’ll walk along that avenue and the hallways of the van Gogh museum where his work remains on permanent display, and I’ll think about the man who was nothing more than a peasant who lived with a prostitute, didn’t make any money in his last ten yers, lived off of his brother, was disliked and consdiered a leech and a failure by everyone including the best artists of the day who for the most part said his work had no hope. And I’ll think about that as I pass people sleeping on benches in the park and wonder which ones are artists and which ones of us merely pass judgement.