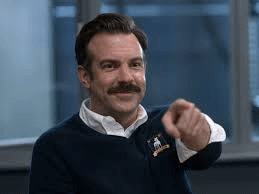

When my brother suggested I watch “Ted Lasso,” I trusted his judgement. He had already nailed it with a few other shows, including “Eureka.” The first time through I enjoyed it immensely, the acting, the writing of course, the timing. It took a few episodes to understand this was not simply a series of set-up/punchline comedy, a method I despise. And it took a few times through the entire three seasons to recognize the primary overall theme at the heart of creator/producer/writer/star Jason Sudeikis’ efforts: This show is all about fathers and sons.

When I struggled with transitioning my book The Iron Scar from the “who gives a shit” stage to the essential-to-be-published “readable and relatable” stage, the answer came while in a writing seminar in Ireland where I had been formulating the final draft of a series of letters from myself to my dad while traveling with my son across Siberia. Writer Elizabeth Rosner, almost as an aside, asked me why the chapters are formulated as letters. “I don’t know,” I told her. “Bad bad answer” she said. I pulled together a response about wanting to have three generations on board, and the reality of my son becoming an adult and moving on in the world the same time my father was approaching his final days. But I still couldn’t answer so I came home from Connemara and chopped my manuscript to small pieces. A few weeks later in a conversation with a friend in Texas, I said, “Tim, I’m losing focus on the theme.” He responded, “I’m not. This is all about fathers and sons. About moving on while trying to hold on. And the metaphor of the train is nothing more than setting.” Between the time my son and I rode the train and the time I wrote the book, my father died. I heard once that the loss of a parent is the greatest loss of security we can face, even at fifty-five years old. Not because we aren’t able to handle the turmoil of life on our own but because that foundation has been rocked.

So I rewrote the entire book as a narrative that takes place on the trans-Siberian railway, with all the characters and unknowns that trip entails, but that’s not what it is about. It’s about relationships, about being between two generations who are about to transition.

Back to Ted.

Sudeikis masterfully weaves every possible father-son relationship into what on the surface is a comedy about an American football coach hired to the helm of a British premier league soccer (football) club.

Right away we have the estranged father as Ted Lasso separates from his wife, and his young son remains with his mother. We also soon learn the powerful impact his own father had on him and the fallout from his father’s suicide when Ted was just sixteen. In England we meet the team, including Jamie Tartt, whose father is physically and verbally abusive, Sam Obisanya, whose father is more of his best friend and mentor, Nathan Shelley, whose Dad is demanding of his son’s talents and seemingly never satisfied, Leslie (male) Higgins who is the proud and dotting father of five boys, Roy Kent, who becomes a surrogate father to his niece, and of course Ted himself, who moves into the father-role to the entire team, the individual players with which he has various degrees of parental conflicts and resolutions.

This is listed as a comedy, but it absolutely fits the bill as a drama as well, placing it in the same vein as shows like MASH which walks that thin line between laughter and tears.

But this isn’t about that. We are in a drama that has become laughable, and the line between what’s funny and what is tragic is a shadow at best.

Both the Mother and Father figures in our lives have served to keep grounded the best efforts of humanity throughout history. We need either to recognize the example or play the part. Almost all aspects of society rely upon those roles to set the strong example with seemingly unconditional love as we push through difficult moments. When hope seems fleeting and one feels “lost in a pathless wood” as Frost proclaims, that Maternal strength or Paternal guidance is almost always enough to help us keep going, knowing that whatever happens we’ll be okay. Even if we lose, we suffer those losses together, and we move on.

There seems to be a lack of parental symbolism in the world, in the nation, in our lives. In fact, more often than not those who should be in those roles these days are appearing more like Jamie Tartt’s abusive and untrustworthy father. It would be perfect if we could always rely upon Sam Obisanya’s Yoda-like dad to turn to, but that’s not the hand we’ve been dealt. In fact, it feels like we’re a player down right now and this time it’s the captain of the team who is absent. That loss of security can be overwhelming.

I do not want to judge. In fact, if we are to do so, I remember Ted’s line, “I hope that either all of us, or none of us, are not judged by our weakest moments, but what we do with it if and when we are given a second chance.” But our foundation has been rocked, and it’s getting harder to find solid ground these days. So we must do what the team does and depend upon each other, pass to each other when we don’t have a clear shot, hold each other up when we’re flailing, and celebrate each other when we work things out.

We will get through this time we are in. We might have to switch our game plan, but we’ve got each other’s backs, and that might be enough.