This morning I woke up about four from a dream so real I looked around the room expecting to see people from a place I used to work; people who just a few deep minutes earlier were sitting next to me in intense discussion. I sat in bed aflush with images of standing in hallways, sitting in my office, standing before classes, walking from building to building; or the early days out in portable buildings, walking to the market with my officemate for lunch.

My heart raced and my breathing became labored and shallow. My BP spiked and my mouth went completely dry. I got up and headed out to the river where the water found my resting pulse. Some seabirds dove for breakfast, and I watched an osprey carry a fish to a nest. Dolphins swam by. The dolphins don’t know about my dream. The osprey might.

With a nod to Jason Isbell: Maybe it’s time to let the old ways die.

I rode that train for almost thirty years, one-way, full speed. When I disembarked, it took me some time to get my bearings; I still can’t always find my balance. Usually I can forget that period of my life, but when I remember incidents, or, like last night, when I wake up awash in the past, I shake.

It is difficult to explain.

There’s nothing from that time I need any longer, and nothing to gain from remembering. It has taken me five years to figure this out, always assuming that since I spent so much time—literally half my life—wading through those murky waters, it must be essential to carry at least some of it forward. But no—and this is where one can get their money’s worth out of therapy: Simply, no. Nothing. Oh, of course at the time the paycheck and benefits, the ability to travel the world on someone else’s dime, all worked for me. But that inner-core sensation that I’m “contributing” my “verse” to the bigger “play,” well, that never materialized for me, so thirty years of pouring oneself into the same bucket with a hole in the bottom is quite discouraging. Don’t misunderstand me; it had serious advantages over nearly every other profession. This isn’t about that. In fact, I still do it somewhere else, and I love it. It was there. It was then. Some people who try and remind me I did some good, had a positive effect on some people, and should be proud of that period, are missing the point. I know what happened; I was mostly there at the time. It is irrelevant. Like watching your favorite baseball team score six runs in a game but lose ten to six. Yes, remind them of how great they did scoring the six runs; then step back.

This is about the self-preservation necessary by living a life which outpaces the past. Sometimes—granted, not always; in fact recently I wrote fondly of my time at a health club in New England where I know I had a positive effect as well, and about where I wish I would have a vivid dream, of course—but sometimes there are no glory days and there is no sense of melancholy. Sometimes those tethers simply tug at the scars, open old wounds. You have to let it go. It’s not always an amicable separation; sometimes it’s a reminder of wasted time, and the best psychological recourse is akin to a bad divorce. Or, better, like you never met the person to begin with. Yes, that would be better—some dreams can kill.

The idea of “moving forward” is so simple and common that the axioms to do so are abundant, and they all are a variation of the need to “face forward” and “take small steps.”

Let’s go deeper:

A nervous breakdown in movies is nearly always represented as a person freaking out, flailing their arms, and screaming or crying or otherwise needing to be slapped upside their head. This makes sense since some visuals are needed. But the reality is a nervous breakdown can be as subtle as the rain. Certainly there can be “emotional outbursts and uncontrollable anger,” but more often it is what cannot be shown appropriately on a screen that dominates the symptoms: withdrawal, a sense of being overwhelmed, not wanting to interact with others, feeling burnt out, moody, low. Your self-esteem evaporates, you feel worthless and unqualified for anything, you make illogical requests, you assume nothing is going to work. You stop showing up. You make horrible, self-destructive decisions to the point that those who had faith in you lose their desire to help.

At first, after a major change, after that significant about face, what you do not yet realize is a nervous breakdown can come disguised as a welcome surprise. It is, in fact, similar to mania in that the person might feel overly optimistic.

Here’s how the experts break it down:

- The honeymoon phase – The first stage of a nervous breakdown is referred to as the “honeymoon” stage and is particularly noticeable when undertaking new work responsibilities or initiatives. There are no warning signs of a nervous breakdown at this time. You are, on the contrary, enthusiastic and committed to your work. You are also highly productive and eager to demonstrate your potential in any way possible. If you do not avoid overworking or implementing effective strategies to deal with stressful situations and get enough rest, you will gradually progress to the next stage.

- The onset phase – This stage is reached when you recognize that certain days are more stressful than others. You have insufficient time for personal needs, family, and friends. As you struggle to keep up with your stressful schedule and workload, your productivity levels begin to diminish. And you may begin to experience some mental and physical symptoms of stress, such as headaches, anxiety, changes in appetite, high blood pressure, and an inability to concentrate or focus.

- The chronic stress phase – Chronic stress sets in when you do nothing to manage the mounting stress of work or other commitments. As a result, your productivity levels decline, and you may start to feel overwhelmed. You begin to withdraw from social situations and exhibit symptoms of mood disorder. In extreme circumstances, some individuals may start to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs to escape their overwhelming negative emotions.

- The burnout phase – Burnout occurs when an individual has reached their limit and can no longer function normally. During this stage, you will neglect your personal needs and self-care and continue to isolate yourself socially. Along with other physical symptoms, headaches and fatigue may intensify.

- The habitual burnout phase – Those unable to recover from burnout and whose symptoms have become a part of their daily lives attain this level. This phase can have a detrimental effect on your career, relationships, and health and cause burnout syndrome or other long-term complications. Therefore, getting assistance as soon as possible is imperative if you are experiencing this phase of a nervous breakdown.

Usually comfort is found in extreme retrospect; that is, you look to times before the place of the fall, when that proverbial garden was still green and the metaphoric apple was still on the tree. You reach back for help from those you knew before all of that time, those without association.

And sometimes you get it, though usually not because there is an overwhelming urge in society to tell people it is a “phase” and they’ll “move past it.”

Ask them to do that to a soldier just back from war; tell them their issues are just a phase and they should move past it. How about this instead: listen. Tell them you’re there if they need you. Call them more than once to see how they’re doing, to talk about something completely present and benign.

Semantically, the words “nervous” and “breakdown” are deceiving because it isn’t the same “nervous” one feels when the roller coaster is clicking to the apex of the ride; it is an internal, simmering, indefinable nervousness more akin to complete and absolute helplessness so that even talking seems irrelevant. And it isn’t a “breakdown” in the category of the car no longer running because the starter is broken. It is more like a stall; all the parts are working, but you have a complete sense of an inability to move. You’re a deer in the headlights.

And often, quite dangerously, there is the overwhelming need to just end the thought process that fuels all of this.

Ask that soldier just back from war what their instincts are when they’re feeling this way. It isn’t to “talk about it” or be told anything at all. And the mere fact one might have to take drugs to get them through is a daily reminder swallowed with water that something is not right and any sense of hope is clearly synthetic.

So what is to be done?

Ironically, you accept that it was a phase you went through, and it is time to move on. You just do not, do not, absolutely do not want to be told that.

Because the dreams will come and you’ll see faces of people you used to eat lunch with, used to share an office with, and your depression with force you to wonder why you wasted so much time with people who couldn’t give a rat’s ass you ever existed at all. And that just fuels your sense of worthlessness. And the cycle begins.

Every single person has to decide for themselves how to deal with this. And no one can tell them how; even a therapist, though any therapist worth their weight already knows this and simply helps someone discover these things on their own.

It is as individual as your dreams.

If it were me? I mean, just speaking hypothetically here, but if it were me what would I do to somehow shed those deeply rooted and tightly clasped feelings of worthlessness?

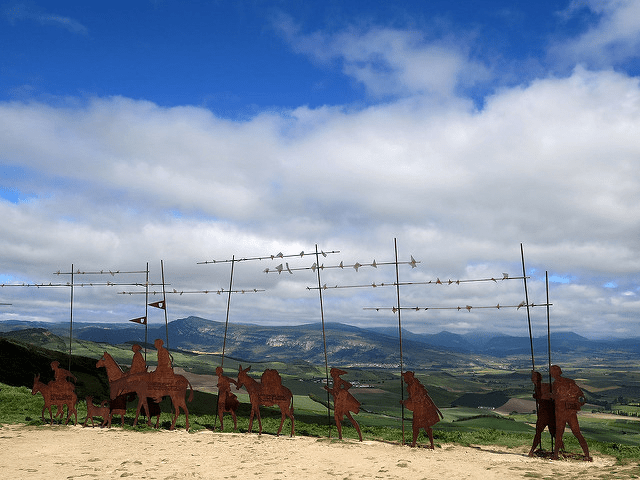

My instinct of course would be to leave like I did throughout my twenties. Maybe I’d go back to Spain, or perhaps sail south on a forty-one foot Morgan Out Island named Pura Vida. Maybe I’d move to some mountains somewhere and go hiking. Yes, that would be nice too. That therapist worth their weight would somehow suggest that having plans like these, escape plans, is essential even though you know you’ll never follow through on any of it. That isn’t the point; the point is about possibility, about choice, about regaining that often taken for granted ability to make our own decisions, something that seems completely gone to a person with this level of depression and hopelessness. They need to feel possible.

It’s kind of like hope but not really. Hope implies some form of stagnancy, of waiting. It needs to be more kinetic than that, like saying, “Hey, let’s get an Airbnb in the Netherlands,” or “You know I think I’ll walk the same route this time instead of doing the Portuguese Route.”

Imagine a brain whose sense of “possibilities” has been extracted. Just for a moment, imagine a person who has not even a remote sense that anything good can possibly ever happen again.

That’s what we’re talking about.

And if you walk into any store today, anywhere, one out of every twelve people are feeling helpless. One out of every twenty completely abandoned.

+++

On the wall of an office I was in a few weeks ago is a poster of an open sky across some western vista. The quote from Richard Bach is one I remember from when I was young.

“Here’s a test to see if your mission on this earth is complete: If you’re alive, it isn’t.”

Too simple? Too elementary? Too, excuse me, pedestrian?”

Maybe.

But I saw the poster and thought of Spain, so there’s that.